Income inequality makes a lot of things we care about worse, according to a new book, The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger, by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett. Looking across 20 or so rich nations and across the 50 American states, Wilkinson and Pickett find that countries and states with greater income inequality tend to have lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality, more mental illness, more obesity, higher rates of teen births, more murder, less trust, and less upward mobility.

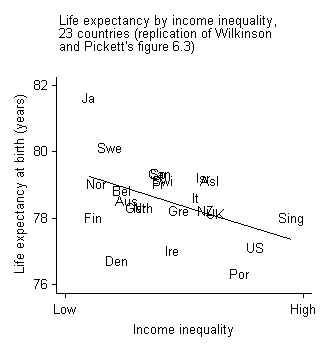

The following plot of life expectancy by income inequality shows a pattern that appears again and again in The Spirit Level.

“The problems in rich countries,” Wilkinson and Pickett conclude, “are not caused by the society not being rich enough (or even by being too rich) but by the scale of material differences between people within each society being too big. What matters is where we stand in relation to others in our own society” (p. 25).

The book has received a good bit of attention. It’s been reviewed in a number of major newspapers and been the focus of events at progressive think tanks in London and Washington, DC. It’s easy to see why. Many progressives worry about inequality. Here is a book, referencing hundreds of social scientific studies and making extensive use of quantitative data, which says, in effect, that many of our social problems can be significantly eased by reducing income inequality.

Is it correct? I was initially skeptical, and after reading the book I remain so.

What’s the causal link?

It wouldn’t be surprising to find that inequality in the income distribution contributes to inequality in health, education, and so on. And there’s plenty of evidence that it does. Wilkinson and Pickett make a different claim: income inequality worsens the average level of health, education, safety, trust, and other good things. How does it do that?

Wilkinson and Pickett say high inequality increases status competition, which in turn increases stress and anxiety, which leads to social dysfunction.

“Greater inequality seems to heighten people’s social evaluation anxieties by increasing the importance of social status…. If inequalities are bigger, so that some people seem to count for almost everything and others for practically nothing, where each one of us is placed becomes more important. Greater inequality is likely to be accompanied by increased status competition and increased status anxiety.” (pp. 43-44)

Here’s how they see stress as the link between income inequality and a key health outcome, lower average life expectancy:

“One of the most important recent developments in our understanding of the factors exerting a major influence on health in rich countries has been the recognition of the importance of psychological stress…. The most powerful sources of stress affecting health seem to fall into three intensely social categories: low social status, lack of friends, and stress in early life…. Much the most plausible interpretation of why these keep cropping up as markers for stress in modern societies is that they all affect — or reflect — the extent to which we do or do not feel at ease and confident with each other. Insecurities which can come from a stressful early life have some similarities with the insecurities which can come from low social status, and each can exacerbate the effects of the other.” (p. 39)

“So how do the stresses of adverse experiences in early life, of low social status, and lack of social support make us unwell? … The psyche affects the neural system and in turn the immune system — when we’re stressed or depressed or feeling hostile, we are far more likely to develop a host of bodily ills, including heart disease, infections and more rapid ageing. Stress disrupts our body’s balance, interferes with what biologists call ‘homeostasis’ — the state we’re in when everything is running smoothly and all our physiological processes are normal.” (p. 85)

Here’s the hypothesized link with obesity:

“People with a long history of stress seem to respond to food in different ways from people who are not stressed. Their bodies respond by depositing fat particularly round the middle, in the abdomen, rather than lower down on hips and thighs…. The body’s stress reaction causes another problem. Not only does it make us put on weight in the worst places, it can also increase our food intake and change our food choices, a pattern known as stress-eating or eating for comfort.” (p. 95)

And educational achievement:

“New developments in neurology provide biological explanations for how our learning is affected by our feelings. We learn best in stimulating environments when we feel sure we can succeed. When we feel happy or confident our brains benefit from the release of dopamine, the reward chemical, which also helps with memory, attention, and problem solving. We also benefit from serotonin which improves mood, and from adrenaline which helps us to perform at our best. When we feel threatened, helpless and stressed, our bodies are flooded by the hormone cortisol which inhibits our thinking and memory. So inequalities of the kind we have been describing in this chapter, in society and in our schools, have a direct and demonstrable effect on our brains, on our learning and educational achievement.” (p. 115)

Other mechanisms are discussed at various points in the book, including oppositional culture, perceived expectations of inferiority, and humiliation. But stress is the key.

An important question here, which Wilkinson and Pickett don’t address, concerns the tightness of the link between the degree of income inequality in a society and the degree of status competition. The United States has the most unequal income distribution among rich countries, but I’m not certain this results in it having more status competition than other countries. Some European nations with less income inequality have a long history of class divisions. American culture is relatively informal, and Americans tend to optimistic about the possibility of upward mobility. As a result, perceptions of status divisions may be less pronounced in the U.S. than in some other nations. The same is true for the American states. The states with the highest income inequality include Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Wyoming. Is status competition greatest in these states? I’m not sure.

How strong is the effect?

Wilkinson and Pickett are convinced that the effect of income inequality on social well-being is real, and perhaps it is. But if so, how strong is the effect? Social scientists frequently discover statistically significant effects that turn out to be trivially small in magnitude.

Look again at the chart above, which shows life expectancy by income inequality across affluent nations. If you follow the regression (“best-fit”) line, you’ll see it suggests that going from very high income inequality to very low income inequality will increase life expectancy by approximately two years (from about 77.5 to 79.5). The same is true across the 50 U.S. states. Is that a large impact?

One way to think about this is to consider how much life expectancy has changed in these countries over time. Let’s compare 1980 to 2006. I got data for these two years from the OECD for 21 of the 23 countries included in Wilkinson and Pickett’s graph. In 1980 the average life expectancy in these countries was 71 years. By 2006 it had jumped to 78 years. This increase is not simply a function of the poorer countries making huge leaps. In the three richest countries — Norway, the United States, and Switzerland — life expectancy rose by five or six years. The smallest rise, in the Netherlands, was four years.

If Wilkinson and Pickett’s estimate of the impact of income inequality is correct, reducing inequality in the United States to Sweden’s level would improve life expectancy by two years. Yet in the past generation life expectancy in the U.S. increased by more than twice that amount. By this gauge, inequality’s effect isn’t an especially large one.

Are the correlations true?

The point-in-time associations in Wilkinson and Pickett’s graphs are their key piece of evidence. Are they accurate? In studies such as this, there almost always is reason to worry about data and measurement choices. I’ll mention just one here. Wilkinson and Pickett measure income inequality for countries using data from the United Nations’ Human Development Report. It’s not a bad choice, but a more reliable source when comparing across nations is the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS). The LIS has data for fewer countries, but if an association is genuine it ought to hold for a subset of the countries examined by Wilkinson and Pickett.

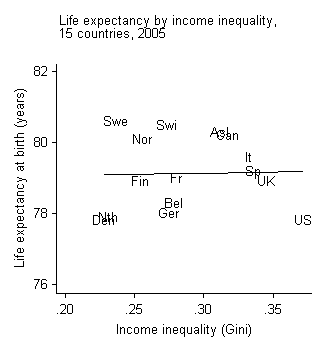

The following chart plots life expectancy by income inequality as of 2005, using LIS data for inequality. There is no association.

Actually, this isn’t so much because of the difference in data source; it’s mainly a function of the particular countries that drop out when switching to the LIS data. The association in Wilkinson and Pickett’s chart rests heavily on the position of Japan, Singapore, and Portugal, none of which are in the LIS database. A small number of countries, often the United States and Japan, exert a good bit of influence on the patterns in a number (though not all) of Wilkinson and Pickett’s scatterplots. This is worrisome.

Are cross-sectional point-in-time associations the appropriate empirical test?

Patterns of association across countries or states at a single point in time may be very useful evidence. Or they might not. With this kind of evidence, we worry about other ways in which countries differ from one another that could be the true drivers of the observed association.

To supplement cross-sectional snapshots, we can, where data availability permits, look at what happens over time. Wilkinson and Pickett presumably would think this a good idea. In the book’s final chapter they note that the level of income inequality has changed in a number of these countries over the last few decades. And in the conclusion to an article that summarizes the book, they say “Standards of health and social well-being in rich societies may now depend more on reducing income differences than on economic growth without redistribution.” If income inequality is reduced, they’re suggesting, life expectancy and other social outcomes should improve; if inequality rises, outcomes are likely to worsen.

Yet The Spirit Level includes virtually no analysis or discussion of over-time developments. There is one over-time chart in the chapter on trust, a brief discussion in the chapter on crime, and a few references to other studies in a summary chapter. But as best I can tell, that’s all.

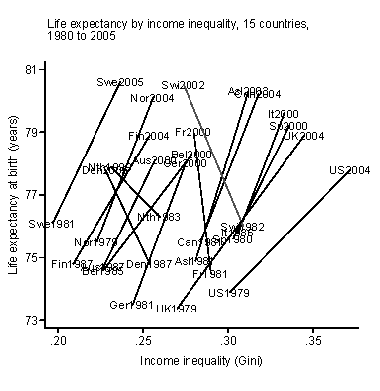

This is an important omission, because researchers who have examined over-time relationships between income inequality and average levels of health have tended to find no support for the hypothesized link (Jennifer Mellor and Jeffrey Milyo; Jason Beckfield; Andrew Leigh, Christopher Jencks, and Tim Smeeding). Here’s one way to see this. The following chart plots life expectancy on the vertical axis and income inequality on the horizontal. Each country is shown at two points in time, around 1980 and around 2005. For each country, a line connects the two data points. In most of the countries income inequality has increased and yet so has life expectancy. That’s not what Wilkinson and Pickett’s argument and findings would lead us to expect. Moreover, in the two countries where inequality was already low and then decreased, the Netherlands and Denmark, life expectancy rose the least.

I haven’t looked carefully at over-time data for the other outcomes Wilkinson and Pickett examine. But a few trends in the United States seem problematic for their argument. Average educational achievement has improved over the past generation even while income inequality soared. Violent crime began increasing in the mid-1960s, well before the rise in inequality, and it has dropped considerably since the early 1990s. Trends such as these don’t necessarily mean inequality has had no effect, but at the very least they call into question its magnitude.

Interestingly, Wilkinson and Pickett report that anxiety, the mechanism through which they believe income inequality causes social dysfunction, has been increasing steadily in the United States and other rich nations over the past half-century. But as they note, that isn’t due to rising income inequality: “That possibility can be discounted because the rises in anxiety and depression seem to start well before the increases in inequality which in many countries took place during the last quarter of the twentieth century. (It is possible, however, that the trends between the 1970s and 1990s may have been aggravated by increased inequality.)” (p. 35). This leaves us with an important unanswered question: Why would income inequality be a key determinant of stress across countries at a point in time, as Wilkinson and Pickett posit, but not within countries over time?

In sum, longitudinal developments offer further grounds for skepticism about the effect of income inequality on average levels of health, education, safety, and other social goods.

What to do

Improving social outcomes is certainly a worthwhile aim. What’s the best way to do it? According to Wilkinson and Pickett,

“Attempts to deal with health and social problems through the provision of specialized services have proved expensive and, at best, only partially effective…. The evidence presented in this book suggests that greater equality can address a wide range of problems across whole societies.”

I wish it were that simple. I share Wilkinson and Pickett’s conviction that it would be good for America and some other affluent nations to reduce income inequality, but this book hasn’t convinced me that doing so would help us to make much headway in improving health, safety, education, and, trust. To achieve those gains, my sense is that our best course of action is greater commitment to specialized programs and services, coupled with poverty reduction.

Then again, I’m not certain that Wilkinson and Pickett are wrong. I’ve focused here mostly on the effect of inequality on life expectancy, because that is the social outcome for which the hypothesized causal link (stress) seems most plausible and because it has received the most attention in prior research. I’m skeptical that income inequality has much of an impact on average life expectancy. But perhaps life expectancy will turn out to be the exception to the rule.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply