How would financial markets assess complicated structured products in the absence of ratings agencies? This column uses the history of emerging economies’ government debt to argue that investment banks used to win market share by building a reputation for quality products. It says that ratings agencies insulated investment banks from reputational rewards and freed them to deal in junk.

When designing the curriculum for crisis predictors of the future, it may be useful to take stock of the way semi-nonstandard economists already think. Take economic historians for instance. We like to think in terms of counterfactuals; to address questions like “If not this, then what?” Take, for example, the critical issue of rating agencies.

People complain about rating agencies’ alleged conflicts of interest. They made money by rating structured products, and they became involved in origination, becoming part of the structured product production chain. And, we are told, they ended up rating poorly, giving triple A to the undeserving (e.g. Freixas and Shapiro 2009). So, the saying went “they would rate a horse.” From all quarters the rallying cry has been “let’s abolish the agencies”.

What’s the alternative? Lessons from the emerging market debt markets

The economic historian’s natural question would be to ask: “if not that, then what?” So close your eyes and try to imagine a world without rating agencies. What would happen? Seems a daunting challenge, no?

Maybe not. We have ways to speculate. Just look at the past and look at what was happening. Of course, there were no structured products – at least, no structured products of the kind that concern us today. But you can look at emerging countries’ government debt. This kind of product is exotic and dangerous enough to be able to tell us something about other dangerous, exotic products. It has been packaged in similar ways in many earlier experiments, and it ended up badly a few times. Moreover, even if government debt started receiving ratings during the interwar period, the rating agencies in those years were hardly as important as they would become later on.

A group of colleagues and I collected data for emerging country debt in various crises – the 1820s, the 1870s, and the 1930s – when about than 40% of emerging country debt went bust (Flandreau, Flores, Gaillard, and Nieto Parra 2009). We did the same for the more recent period. And then we just looked at the performance of underwriting banks. Were they equal before default? And what about today?

The history of big banks’ instruments

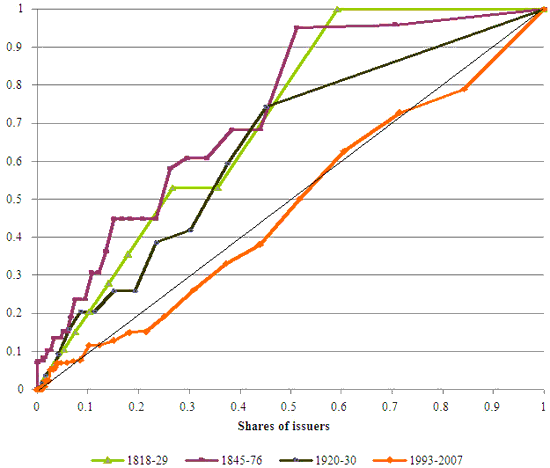

We found striking results, summarised in Figure 1. It shows the concentration of default according to market share, starting with the smallest banks, for each lending spree episode. We thus examine the percentage of bad securities held by banks of various sizes, regardless of quality.

Figure 1. Defaults and market share

Figure 1 suggests that large banks were cautious prior to 1933. For instance, in the past, banks with 10% (or 0.1) of the total amount of securities underwritten suffered about 20% (or 0.2) of defaults. Today, the proportion is about 10%. More generally, we see that today the curve that describes the quality of underwriting according to size is more or less the diagonal line, meaning that default rates are uniform across intermediaries.

Such uniformity is new. Historically, as the curvature of the distribution of past defaults shows, small banks “specialised” in bad securities while large banks mostly dealt with good stuff. We argue that the public understood this, allowing good banks that signalled their value to maintain their larger market share, while small banks could not and remained small.

In plain English, if you bought, say, a Rothschild security in the 1820s or 1860s, you were pretty safe, and the same holds for a JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM) security during the 1920s. Beyond that, there were perils that people seem to have understood.

But today the world is much different. All houses sell similar instruments. The market is also much more competitive than ever before. Only a few houses participate today, but the edge of the market leader (JP Morgan) is way smaller than the edge of the market leader during, say, the interwar period (JP Morgan led the market then too, but its lead on number two was huge). Today, the leader does just the same as the other banks, and we found that the proportion of lower-rated or speculative-grade securities has increased.

Why is this happening? The less informed rate; the more informed sell

We argue that this has a lot to do with the existence of rating agencies. They provide the market with a grade for a country’s debts. The benefit that a bank can secure from associating its name with good products is smaller. Market share no longer means reputation. It just means market share. And reputation doesn’t mean much either. If a subprime metaphor is apt here, the result is that you can very well run into trouble with a Lehman (OTC:LEHMQ) product.

In other words, the rating provided by the agency is liability insurance for the bank. “I sold you junk, but the rating agency rated it junk, so why complain? It did not? Never mind, these guys always make mistake. They ought to be regulated.”

That plays well. We all know that Joe Stiglitz played on that tune. But our research leads us to a different conclusion; it is the less informed who rate, and the more informed who sell. Isn’t this a bit counterintuitive? The extent to which rating agencies have been playing a role that was mightily useful for investment banks should not be discounted when we focus our criticism on them.

Conclusions

Banks used to pay for their reputation with lost revenues and a large upfront capital. They now do this with taxpayers’ money and US Treasury Secretary’s underwriting. And rating agencies bear the brunt of the regulatory reaction. While the data ought to be collected for other markets and business line, it is our strong presumption that what is true for emerging markets is true for many other sectors.

One last word. In one of our interviews with the emerging market debt community in New York, we were told “Investment banks would underwrite anything – for a fee.” Does it ring a bell? Between the investment banker who would underwrite anything for a fee and the rating agency who would rate a horse (presumably for a fee, too), what would you choose?

References

•Freixas, Xavier and Joel Shapiro (2009). “The credit rating industry: Incentives, shopping and regulation,” VoxEU.org, 18 March 2009.

•Flandreau, Marc, Juan Flores, Norbert Gaillard and Sebastian Nieto Parra, “The End of Gatekeeping. Underwriters and the quality of sovereign bond markets 1815-2007” NBER Working Paper 15128.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply