Once I was talking to my boss at Provident Mutual about exotic options, like barrier, knock-out, and knock-in options. As I described them to him his reactions were:

- Why would I want to take that risk?

- But when describing the other side of the trade, he would say “That’s an attractive proposition.”

And vice-versa. He was a bright guy, but I don’t think his opinions were very different from what most people would think who have a moderate knowledge of the markets. Asymmetric payoffs are typically favored by those that can earn a lot, even if the odds are small.

The same is true of Credit Default Swaps [CDS]. There are a lot of players that want to speculate on the demise of companies, hoping for a big payout, even if the odds are small, partly because the amount they pay to gamble on the risk is also small.

The markets for single company CDS are thin because there are few natural counterparties that want to nakedly go long credit risk. Those wanting to nakedly short credit risk therefore have to pay a premium to do so, usually higher than the credit spread inherent on a corporate bond of the same maturity.

And if one or two hedge funds want to do it “in size,” guess what? The dealers in the CDS market will back off considerably, and make them pay through the nose. No dealer wants to take the risk that an informed trader knows something he doesn’t. They will raise the levels that one would have to pay to bet on the risk so high that some others might be willing to take the other side of the trade.

Now some investment journalists naively think that there is a strong correlation between CDS prices and probability of default. The CDS market is a thin market, for reasons mentioned above. Before I would say that there is a “creditor panic” going on, I would look at the corporate bonds of the company in question, and see if the yield spreads are “blowing out.”

Typically, the CDS market is quick to react, but with a lot of false signals. The corporate bond market is slow to react, and sometimes misses problems. The stock market is in-between, which is why I would look at the stocks of the companies when I was a corporate bond manager.

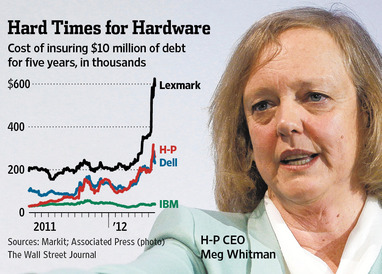

So, when I read articles like these:

- Someone Is Getting Really Nervous About HP’s Debt

- Debt Markets Aren’t Only Worried About HP, but Dell and Others, Too

- H-P: Swap Buybacks for Paybacks

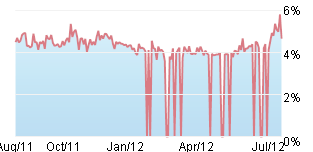

I say to myself, “What is happening in the corporate bond market? Is it panicking?” The CDS markets say this:

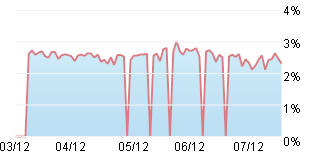

But when I look at the corporate bond market for the same names, I see no panic. Here is the yield for a similar maturity HPQ bond:

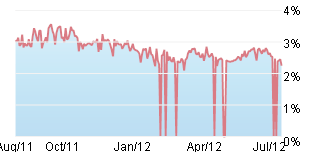

And for a similar maturity DELL bond:

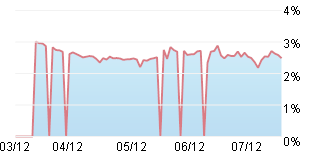

And for a similar maturity Xerox (XRX) bond:

Finally, for a similar maturity Lexmark (LXK) bond:

Aside from the Lexmark bond, there is no hint of trouble. Lexmark is a small company, with two small bond deals, and as such is more volatile. Still, there is no real panic there. Panic means the prices of the bonds is below $80, and these bonds still trade over $100.

In most cases, you could short the corporate bonds, and offer credit protection through CDS, and make risk free profits.

There is no panic going on in the technology company bond market, aside from Lexmark, of those names that have been mentioned.

It’s hard to spook the bond market for a liquid bond issuer; it is easy to spook the CDS market. That’s why I don’t trust appeals to rising CDS spreads if the bond market does not validate them. Big markets do not need small markets for validation; rather, small markets need big markets for validation.

An Appeal to Journalists

When talking about default, you need to spend more time on the bond market and less time on the CDS market. Yes, the CDS market tends to lead the bond market, but this relationship has a lot of noise, and offers a lot of false positives. Far better to look at the bond market. When the bonds of any company drop below $80 per $100 of par, there is trouble, and usually a juicy story, with considerable concern as to whether the company can survive.

The CDS market is driven by speculators who are probably right more often than wrong, but not by a large margin. Avoid using that market to write stories, because it only lends to sensationalism, and does not reveal imminent trouble, unless the bond market agrees.

Final note: it is easy to go over to FINRA TRACE and get the bond yield data, even easier then getting CDS data if you don’t have a Bloomberg terminal.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply