Last week The Economist described what it called a “slow-motion run in the funding markets” in Europe — in other words, a gradual but steady run on European banks, as depositors remove their money from European banks and put it in places that are seen to be safer. It’s worth taking a look at some data to see how significant this phenomenon is.

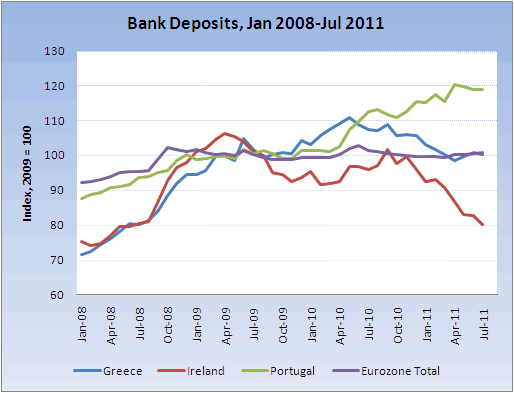

First, let’s look at the troubled euro-zone perihpery countries. The following chart shows the total level of deposits with monetary financial institutions (“MFIs”, which basically means banks and money market accounts) in Greece, Ireland and Portugal. For comparison, the total level of deposits within the entire euro-zone is also presented. (All data is from the ECB and is through the end of July 2011 unless otherwise noted.)

Ireland clearly stands out as having experienced a large net withdrawal of deposits over the past year. Perhaps surprisingly, banks in Greece have seen their deposits fall by only a relatively modest amount (about 10%) since the summer of 2010. And for the euro-zone as a whole, total deposits have been essentially flat.

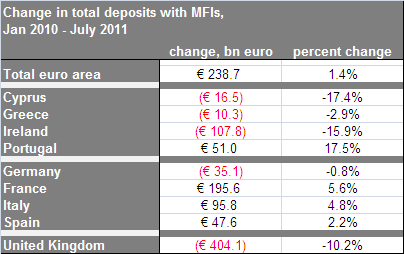

But this hides some important details. If we compare the three most troubled periphery countries with other euro-zone countries, we find that Cyprus has actually seen the greatest percentage decrease in deposits since the start of 2010. But Germany has also seen total deposits shrink by a bit, and, perhaps alarmingly, even though it is not in the euro-zone, the UK has experienced a very significant fall in total deposits with its MFIs. (Note: UK data is through June 2011.)

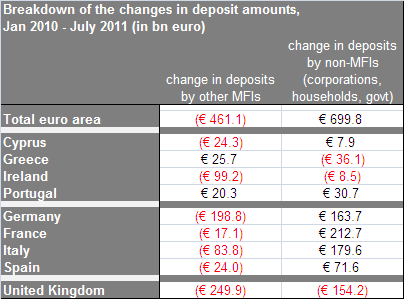

This still doesn’t tell the whole story, however. To really understand what’s going on it’s useful to break the change in deposits held with European MFIs into two pieces: deposits owned by other MFIs, and deposits owned by non-MFI entities such as households and non-financial corporations. That story is told in the following table.

Now we can understand why Greece, for example, doesn’t show a bigger fall in bank deposits in the aggregate statistics: households and corporations have indeed removed money from Greek banks at a substantial rate over the past 18 months (withdrawing about 15% of their deposits), but much of this has been replaced by increased deposits by other MFIs, reflecting the inflow of funds into the Greek banking system resulting from the various international measures to support it.

The truly troubling thing to note in the table, however, is the rate at which financial institutions have been withdrawing money from European banks. This has particularly affected those countries that have traditionally been large international money centers, such as Germany, the UK, and to a lesser degree, Ireland, but it has affected all of the major European economies to some extent. To varying degrees these withdrawals by financial institutions have been offset in the large euro-zone countries by steady increases in the deposits made by domestic residents and corporations (i.e. non-MFI deposits), leaving the overall level of deposits in the euro-zone roughly unchanged. But it seems very clear that the world’s big banks and other financial institutions are indeed moving their funds out of Europe at a significant rate.

Fortunately for them, the big euro-zone countries all have a large domestic base of depositors that has continued to deposit a portion of their earnings into their own banks, so alarm bells have not yet been sounded. But the fall in deposits by MFIs indicates that international money managers are nervous about keeping their money in European banks. And if their nervousness begins to spread to households and non-financial corporations (the way that it clearly has in Ireland and Greece, for example), this hidden slow-motion bank run will suddenly become very visible, and very dangerous.

One last note: according to this ECB data, MFIs in the UK have seen by far the largest falls in deposits over the past year and a half in absolute terms. But keep in mind that the UK does not even use the euro. That’s a potentially chilling reminder that if Europe’s debt crisis worsens and spreads, there’s every reason to believe that its effects will be felt well beyond the euro-zone.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply