What can the iPhone tell us about the trade imbalance between China and the US? This column argues that current trade statistics greatly inflate the value of China’s iPhone exports to the US, since China’s value added accounts for only a very small portion of the Apple product’s price. Given this, the renminbi’s appreciation would have little impact on the global demand for products assembled in China.

At the centre of global imbalances is the bilateral trade imbalance between China and the US. Most attention to date has been focused on macro factors and China’s exchange-rate regime. Little attention, however, has been paid to the structural factors of economies and global production networks that have reversed conventional trade patterns, transformed the implications of trade statistics and weakened the effectiveness of exchange rates on trade balances.

Today’s trade is not that experienced by the British economist David Ricardo two hundred years ago (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2008). It is almost impossible to define clearly where a manufactured product is made in the global market. This is why on the back of an iPhone one can read “Designed by Apple (AAPL) in California, Assembled in China”. In this column, I use the smartphone in your pocket to argue that current trade statistics have distorted the reality of the Sino-US trade imbalance and the appreciation of the renminbi would have little impact on the imbalance.

How iPhones are produced

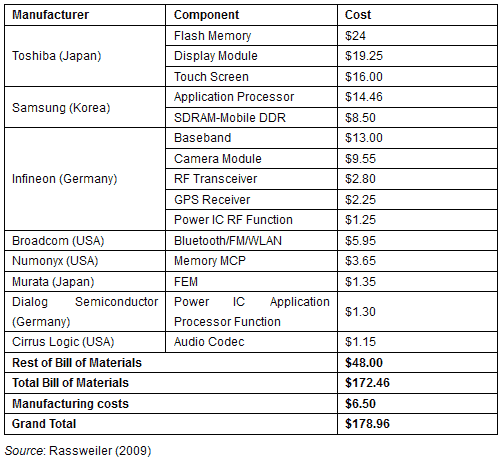

The iPhone is designed and marketed by Apple. Apart from its software and product design, the production of iPhones primarily takes place outside of the US. Manufacturing iPhones involves nine companies, which are located in China, South Korea, Japan, Germany and the US (Table 1). All iPhone components produced by these companies are shipped to Foxconn, a Taiwanese company located in China, for assembly into final products and then exported to the US and the rest of the world.

By any definition, the iPhone belongs to high-tech products, where the US has an indisputable comparative advantage and China does not domestically produce any products that could compete with it. However, the iPhone trade pattern is not what is predicted by either the Ricardian comparative advantage theory or the Heckscher-Ohlin theory. The manufacturing process of the iPhone illustrates how the global production network functions, why a developing country such as China can export high-tech goods, and why the US, the country that invented the iPhone, becomes an importer.

Table 1. Apple iPhone 3G’s major components and cost drivers

iPhones and the Sino-US trade imbalance

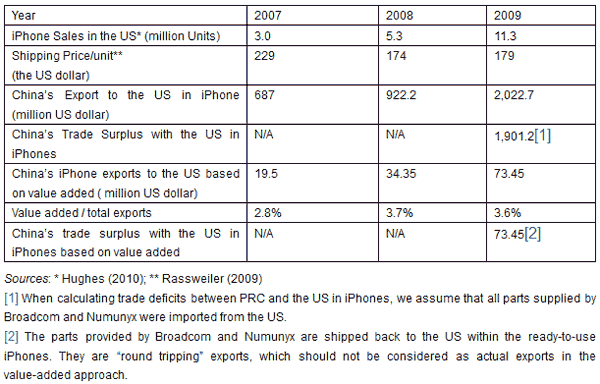

The shipment of the ready-to-use iPhones from China to the US is recorded as China’s exports to the US. Using the total manufacturing cost $178.96 as the price of the iPhone, China’s iPhone exports to the US amounted $2.0 billion in 2009. Assuming that the parts supplied by Broadcom, Numonyx and Cirrus Logic, valued at $121.5 million, were imported from the US the iPhone alone contributed $1.9 billion trade deficit to the US, about 0.8% of the US trade deficit with China (Table 2).

On the other hand, most of the export value and the deficit due to the iPhone are attributed to imported parts and components from the third countries and have nothing to do with China. Chinese workers simply put all these parts and components together and contributed only $6.50 to each iPhone, about 3.6% of the total manufacturing cost (e.g. the shipping price). The traditional way of measuring trade credits all $178.98 to China when an iPhone is shipped to the US, thus exaggerating the export volume as well as the imbalance. Decomposing the value added along the value chain of the iPhone manufacturing suggest that, of the $2.0 billion iPhone export from China, 96.4% is actually the transfer from Germany ($326 million), Japan ($670 million), Korea ($259 million), the US ($108 million) and others ($ 542 million). All of these countries are involved in the iPhone production chain.

If China’s iPhone exports were calculated based on the value added, i.e., the assembling cost, the export value as well as the trade deficit in the iPhone would be much smaller, at only $73 million, just 3.6% of the $2.0 billion calculated with the prevailing method (Table 2). The sharp contrast of the two different measurements indicates that conventional trade statistics are inconsistent with trade where global production networks and production fragmentation determine cross-country flows of parts, components, and final products. The traditional method of recording trade has failed to reflect the actual value chain distribution and painted a distorted picture about the bilateral trade relations. The Sino-US bilateral trade imbalance has been greatly inflated.

Table 2. iPhone trade and the US trade deficit with China

iPhone trade and the appreciation of the renminbi

Many believe that appreciation of the renminbi would be an effective means to solve the Sino-US trade imbalance. Appreciation proponents ignore the fact that the appreciation can only affect a small portion of the cost of made/assembled-in-China products. If the renminbi appreciated against the US dollar by 20%, the iPhone’s assembly cost would rise to $7.80 per unit, from $6.50, and add merely $1.30 to the total manufacturing costs. This would be equivalent to a 0.73% increase in total manufacturing costs. It is doubtful that Apple would pass this $1.30 to American consumers. Even a 50% appreciation would not bring a significant change in the total manufacturing cost, as the appreciation would only affect the assembling cost. Therefore, the expected pass-though effect of the renminbi’s appreciation on the price of the iPhone would be zero and the American consumers’ demand on the iPhone would not be affected. The appreciation of the renminbi would have little impact on the Sino-US trade imbalance.

Could the iPhone be assembled in the US?

There is no doubt that US workers and firms are capable of assembling iPhones. If all iPhones were assembled in the US, the $1.9 billion trade deficit would not exist. There are two possible reasons for Apple to use China as an exclusive assembly centre for iPhones. One is competition, the other is profit maximisation.

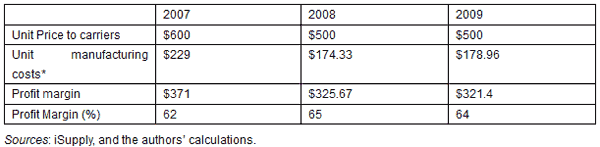

The gross profit margin of the iPhone was 62% when the phone was launched in 2007, then rose to 64% in 2009 due to reductions in manufacturing costs (table 3). If the market were perfectly competitive, the expected profit margin would be much lower and close to its marginal cost. The surging sales and high profit margin suggest that the intensity of competition is fairly low and Apple maintains a relative monopoly position. Therefore, it is not the competition but profit maximisation that drives the iPhone’ s assembly to China.

Table 3. Profit margin of the iPhone

An interesting hypothetical scenario is one where Apple had all iPhones assembled in the US. Assuming that the wage of American workers is ten times as high as those of their Chinese counterparts, the total assembly cost would rise to $68 and total manufacturing cost would be pushed to approximately $240. Selling iPhones assembled by American workers at $500 per unit would still leave a 50% profit margin for Apple. In this hypothetical scenario, the iPhone could contribute to US exports and reduce the US trade deficit, not only with China, but also with the rest of world. More importantly, Apple would create jobs for US low-skilled workers.

In a market economy, there is nothing wrong with a firm pursuing profit maximisation. Governments should not restrict such behaviour in any way. However, corporate social responsibility has been adopted as a part of corporate values by many multinational companies, including Apple. Employing American workers to assemble iPhones may be an effective way to practice corporate social responsibility.

Concluding remarks

Due to the limitations of the data, it is not possible to outline a more detailed distribution of the iPhone’s manufacturing value chain across all countries involved. However, adding additional countries and parts into the analysis would not change the bottom line – the value added created by Chinese workers accounts for only a small portion of a ready-to-use iPhone, so current trade statistics greatly inflate the value of China’s iPhone export to the US as well as the corresponding trade imbalance. Given this, the renminbi’s appreciation would have little impact on the global demand of the products simply assembled in China.

References

•Grossman, Gene M and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg (2008), “Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring”, American Economic Review, 98(5):1978-1997.

•Hughes, N (2010), “Piper: 15.8M US iPhone sales in 2010, even without Verizon”, Apple Insider, 6 January.

•Rassweiler, A (2009), “iPhone 3G S Carries $178.96 BOM and Manufacturing Cost, iSuppli Teardown Reveals”. iSuppli, 24 June.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply