The Federal Reserve released the 2005 FOMC transcripts this week. Attention quickly turned to the Fed’s view of the growing housing bubble. Calculated Risk finds some very prescient warnings from then Atlanta Fed President Jack Guynn, who describes housing as an “accident waiting to happen.” Bloomberg continues with the obvious path of criticism:

Federal Reserve staff and policy makers identified a housing bubble in 2005 and failed to alter a predictable path of interest-rate increases to slow down the expansion of mortgage credit, transcripts from Open Market Committee meetings that year show.

Led by then-Chairman Alan Greenspan, the FOMC raised the benchmark lending rate in quarter-point increments to 4.25 percent from 2.25 percent at the end of December 2004. The committee also removed uncertainty about the pace of rate increases by telegraphing that future moves would be “measured” in every statement.

The “measured” pace language helped fuel the housing boom by keeping longer-term interest rates low and was inappropriate at the time given the uncertainties about both inflation and asset prices, said Marvin Goodfriend, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

“It was a major mistake of the Fed,” said Goodfriend, who attended some of the 2005 meetings as a policy adviser to the Richmond Fed. “It gave markets a sense that the Fed was on top of everything to a degree that wasn’t the case. It gave the impression that this was a mechanical adjustment to normality. The market was overconfident.”

David Beckworth follows up:

With the release of the 2005 FOMC transcripts we learn that the Fed was aware of the housing boom but failed to alter monetary policy. Among other damning evidence, we find this gem in the December 2005 FOMC meeting. It shows the real federal funds rate compared to the Fed’s estimate of the equilrium or neutral real federal funds. There is a striking gap that emerges during the early-to-mid 2000s. This indicates the Fed was highly accommodative and aware of it.

The problem with this criticism is that it fails to capture the implications of the low interest rate environment for the economy at large. Andy Harless, in a response to Beckworth, beats me to the punch:

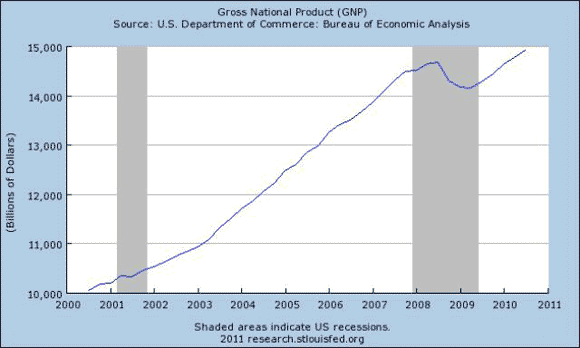

I just don’t get how this Fed-too-easy story is consistent with the data on NGDP growth. From 2001 to 2006, NGDP grew at an annual rate of 5.3%. That’s actually slightly slower than the prior 5 year period (5.4%) or the 5 years before that (also 5.4%). If the Fed was too easy in 2002-2003, then that period should have been followed by a huge boom in NGDP. It wasn’t. All that happened was that NGDP grew (almost) fast enough (about 6% annually) to make up for the slow growth during the recession and the year of weak recovery that followed. As far as I can tell, the data vindicate the judgment of Fed officials who ignored the model-based estimates.

Looking back at the path of nominal GDP over the last decade:

Considering the path of employment, output, and prices, I have difficulty arguing that the level of rates was significantly wrong. I tend to think that regulatory failure was the primary Fed error – if the Fed realized the housing market was evolving into a bubble, shouldn’t they have been more focused on the kind of mortgage lending that was taking place? Shouldn’t, in their jobs as banking regulators, made more aggressively us of stress tests before housing prices began to melt? More directly, from a regulatory perspective, the Fed simply lost view of its societal function. Via Rajiv Sethi:

But even in our very imperfect world, might we not have been able to stabilize output and employment by returning quickly and forcefully to the original mandate of the Federal Reserve, to channel credit preferentially to productive uses?

The Fed was probably too captured by a free markets ideology to seriously question the wisdom of channeling so much capital into housing, which was really less about capital investment and more about consumption. And, in their defense, attempting to direct capital flows is indeed tricky business fraught with peril. But allowing everybody and their cousin to get a half million dollar mortgage with no income documentation? Addressing that issue seems like it should have been doable.

Still, rather than lay all the blame at the feet of monetary policymakers, I think the real question we still need to resolve is more fundamental. Turning the question around, why did the US economy struggle so dramatically this decade that the Fed was pushed into a very low interest rate environment? The jobs record is simply unprecedented – a decade with no job growth. To what extent are domestic policymakers to blame? And was it domestic policy at all? I don’t recall the 1970’s as a policy paradise, but at least jobs were created over that decade. Answers will vary; mine is that US policymakers across the ideological spectrum allowed and even supported the pursuit of foreign nations’ mercantilist policies on a unprecedented scale, thereby distorting global patterns of production and consumption in a way that fundamentally hobbled the US economy. If this is true, how can we chart a path back?

In short, I think we need to understand why the last decade was jobless – it is tempting to blame the Fed, but the story is likely deeper. Until we do, I don’t think I can definitively say the next decade will be any different.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Overconfidence was the case of FED before the recession and even after. But the irony is, they have no choice now really. They have to show some muscle and try to convince the markets that they have the economy under control. And they’re trying to do it by QE2. Fortunately, they seem to convince them despite the obvious fact that it’s just postponing the inevitable.