When the Fed truly begins to back off its low rates and quantitative easing (QE), we should expect bond rates to rise and bonds to fall. The right strategy is to buy the short end, let the rise happen, then swap to the long end. This seems to encapsulate the Chinese strategy, which has been to sell the long bond and buy in the shorter end (two year primarily). Even if rates jump, and the short stuff drops, they can be held to maturity to maintain value – but moving short too early risks dreadfully low rates and dismal returns while the longer instruments reward their holders.

It is tricky to throw the magic sticks and divine the Fed, since the Fed purposely obfuscates its intentions. Case in point: after the recent raise in the discount rate it has gone out of its way to say real tightening is a ways off.

It is also tricky to listen to the pundits. Right now they go both ways:

- The Black Swan guy, Taleb, says “every single human being” should short Treasuries

- Everyone’s favorite analyst, David Rosenberg, says to go long Treasuries

Too bad they are on both sides:

the greatest returns are when a widely-held belief of investors proves incorrect

Instead we have a balance of views. You can see this in the behavior of bonds recently. The long bond was climbing (rates fell) through most of the Hope Rally, but beginning in October began to fall (rates rose). So far in 2010 it has been sideways. We sit on a cusp: will rates continue to rise to above 5%? Or are they about to drop?

This is a complex subject, and I will walk through it in a series of posts, beginning with the conventional wisdom of fundamentals.

Bond Fundamentals

How to take the confusions of macro economics and in particular the confusions of Ben Bernanke and create an outlook for bonds? Let’s look at three primary drivers of rates:

- Yield Curve

- Fed Policy

- Inflation

Yield Curve

The long bond normally rises early in an economic recovery, based on a theory that recovery it carries with it an expectation of an increase in long term rates. A survey of economic literature will show there is no consistent view as to why this happens. Instead, it usually is seen that the yield curve flattens as a recession approaches, so the inverse is argued for a recovery. Summary:

- bull steepens the yield curve

- bear flattens it

The yield curve is very steep, the steepest in history. Is this bullish?

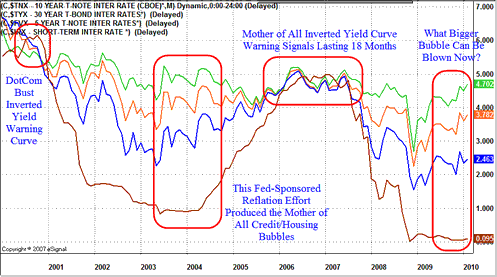

The chart shows that last time spreads widened like this, in 2003-4, the Greenspan Bubble drove us into The Mother of All Inverted Curves, and we fell into the current credit crisis. Does this denote a similar bubblicious recovery brewing?

Mish notes that normally the curve steepens as commercial banks rush to lend, a signature of a recovery coming. As my prior post should have made clear, this ain’t happening. Instead, bank lending is a record declines, both for business and for mortgages. So no recovery there.

GDP has nonetheless been increasing, and that indicates some form of recovery. I have written that “every W starts as a V”, as I think we will have a double dip, but first a V-shaped recovery. The V is visible in GDP over the past 3 quarters, in industrial production charts, and in personal consumption (see this prior post for charts).

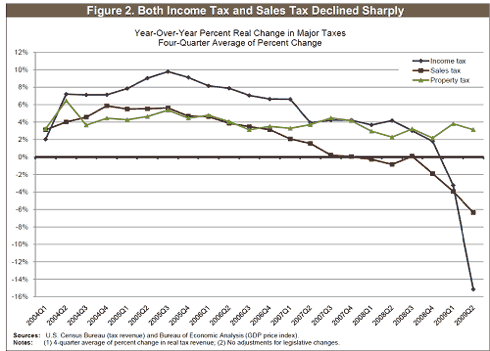

Yet we have seen a complete collapse in tax revenues at the State level, an indication that there is no recovery emerging in the private sector. This chart from Greater Depression for US Rebuts ‘Recovery’ Talk should be of great concern to the greenshoots advocates – it shows all we have so far are gimmicks and Federal life support.

As the author, Jeff Nielson, remarks:

Obviously the U.S. economy is represented by the collective economic performance of its 50 states. Yet in the fantasy-world of U.S. economic propaganda, we are supposed to believe that nationally the U.S. economy can be improving, while state-by-state the economy continues plummeting downward. The only difference between the U.S.’s “national economy” and the “state-by-state economy” is that the federal government has incorporated far more statistical contrivances to distort the numbers

Conclusion: steep yield curve is not bullish on a recovery. The faux recovery reflects government life-support. Implication is that when life-support is pulled, rates could drop.

Central Bank Policy

The central bank has influence particularly by driving rates down, as the Fed is doing. This draws the whole curve down. You will see commentary about “the yield curve is steeper than ever before.” This is not necessarily because of a coming recovery, but the Fed holding down the short rates. The “steep” long rates are at lower levels than normal, too.

The Fed is in a terrible pickle exiting from all these measures. As Jeff Nielson argues, given over $50T of US Dollar debt:

a 1% increase in interest rates sucks $500B out of the economy, or a 4% decrease in GDP

Now, rates don’t float up all the debt consistently, and stickiness can slow the effect, but given the huge overhang of debt, the impact is substantial. Consequently expect the Fed to resist pushing rates up.

Doug Noland notes that the real exit strategy is to leave the Fed Funds rate low, and increase interest on reserves held at the Fed:

The Fed has signaled that it is essentially scrapping its previous policy of carefully managing a targeted “fed funds rate” – or essentially the overnight rate for the inter-bank/financial institution lending market. Traditionally, the Fed would manage the fed funds rate to its target level by adding or subtracting system liquidity. With the Trillion or so of Fed-induced excess reserves, it is no longer practical for the Fed to manage the overnight rate as it has in the past. Time for new doctrine.

One of his key insights is that the Fed really doesn’t control rates like a light switch. To raise the Fed Funds rate, the Fed would withdraw a lot of liquidity, and as it does this, the bond buyers are likely to front-run the Fed’s intentions. Hence the Fed will avoid that.

Antal Fekete recently commented that this can cause a chain of destruction:

1. Speculators buy long and sell short, taking a spread, and as long as the Fed keeps the yield curve steep by compressing the low end, this is a safe play

2. Rising short rates could squeeze, but given the huge quantity of short stuff being rolled over to finance the deficits, there is room for this straddle to continue

3. The demand for long bonds to be held keeps long rates lowish

Thus the Fed can continue this way, but the money does not flow back into the real economy, it stays within the easy speculation market. The “destruction” is not of Treasuries, but of private investment. This cannot continue indefinitely, as the flat-to-down private economy provides too few tax revenues, and the government life support turns into a debt-driven Ponzi scheme. It can continue for a while, however.

This is bullish for bonds, but based on a profound confusion by Bernanke over the impact of his policies. His statements suggest he is back on the Philips Curve fallacy, that we need to reflate to avoid high unemployment, as if economic growth is bad for employment. Nuts.

Thus is also bearish for bank lending. Banks would be inclined to stay in the speculation trade, and slow down the fixing of their balance sheets. As summarized in Fed Chooses to Exit through the Eye of a Needle:

[T]here are major flaws to this strategy. The Fed pays interest on reserves with yet more deposits held at the central bank. Therefore, paying interest on reserves further increases commercial bank deposits held at the Fed, and those new deposits will accrue interest as well…and so on.As a result, by choosing to not sell assets and drain liquidity from banks, the unwinding of their balance sheet will take many years.

Finally, consider fiscal policy: we have $1T deficits as far as the budget is projected, and Obama is hell-bent to increase this even more with Obamacare spending and possibly a second stimulus; plus policies which hamper GDP, such as tax increases and regulatory regimes like Cap&Trade. These policies will suppress GDP, and deepen the hole, plus require huge increases in bond issuance. Likely consequence is continued problems in private debt issuance and lending to business, as Treasury crowds out private bonds.

Conclusion: given the need to roll over the short term T-Bills and fund a huge increase in the deficit, look to the Fed to keep rates as low as they can get away with.

Inflation

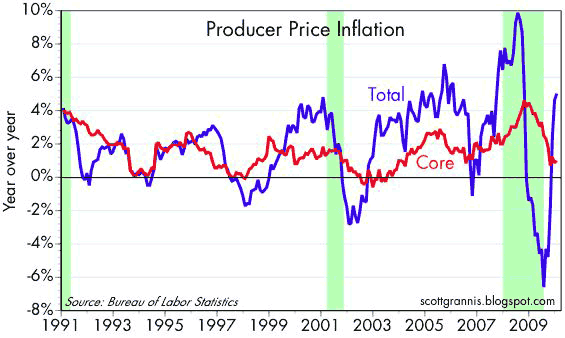

Inflationary expectations can push rates up, as deflation can pull them down. The steep curve has been touted as an indication of inflation fears. The recent CPI report should dispel that. The PPI however came out the other way, causing some pundits to say deflation is not a threat:

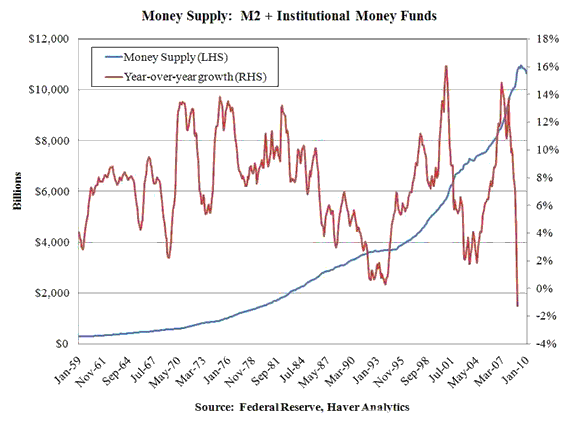

If you apply this logic to bond fundamentals, it says the Fed should start tightening right away! They clearly do not see it that way, or are jawboning about rates and plan to start rising them surprisingly quickly. Or maybe not, as a look at monetary aggregates points to a deleveraging of debt and deflation:

What is curious is how the spread between the inflation-adjusted bonds, TIPS, and the long bond, have moved recently. As Treasuries have gone up, TIPS have stayed flat, suggesting Treasuries are building in inflation of 2.5%. Given how extraordinary the panic was at the V bottom in this chart, a simpler explanation (which the analyst of the post also mention) is that the market has reverted back to a normal spread and is still uncertain as to inflation.

Conclusion: neither the Fed nor the underlying indicators point to inflation starting. We can take that off for the moment as driving rates up.

Fundamentals would conclude that rates will stay relatively low and bonds buoyant. Next time I will look at exogenous forces that could upset the best-laid plans of the Fed, such as sovereign debt failures in Europe or foreign buyers leaving the Treasury markets.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply