Did allowing financial institutions to become “too big” play a role in the financial crisis? This column argues that being “too interconnected” is also a factor, and that US accounting standards should recognise gross derivatives exposure on the balance sheet to make this interconnectedness, and the resulting exposure, clear.

By now there is general agreement that a financial institution can not only be “too big”, but also “too interconnected” to fail. But how do we measure what it is to be too interconnected?

This is where accounting enters the picture, for it turns out that some accounting systems show important interconnections, whereas others do not. Moreover, when interconnections are revealed on balance sheets, they have an important impact on one measure of risk, the leverage ratio, which is supposed to supplement the traditional risk weighted capital adequacy measures under the Basel rules.

Are we primed for another crisis?

Properly measured, leverage is still at the same level as at the peak of the bubble in late 2007. The conditions for a new systemic crisis are thus still in place.

Why has the leverage ratio, defined as total assets divided by total capital, become popular? Because it directly shows the maximum percentage loss a bank can sustain on its assets before it loses all of its capital. For example, if the leverage ratio is 50, capital disappears if the bank loses on average 2% on its assets. This is why some observers have proposed adding this crudely calculated leverage ratio to the standard risk-weighted capital ratios under the Basel regime.

In practice this idea will immediately encounter a fundamental conceptual problem in the context of making transatlantic comparisons, given that the EU uses different accounting principles (International Financial Reporting Standards or IFRS) than the US, which follows the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles or GAAP.

These two accounting systems generally yield similar results, but they present a completely different picture in the case of derivatives because exposure to this particular financial instrument is reported gross under IFRS, but net under GAAP. This makes a huge difference, as illustrated by the following two examples.

Accounting for derivatives: IFRS vs GAAP

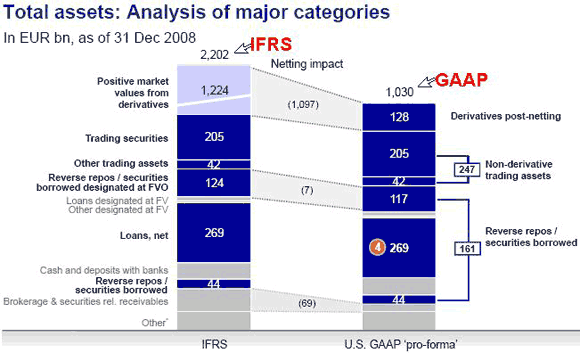

Deutsche Bank is among the few banks that report their balance sheets under both GAAP and IFRS. Under IFRS, its balance sheet shows assets of around €2 trillion for 2008. In order to show how much its leverage has fallen, Deutsche Bank has published its own evaluation of how large its balance would be under GAAP, arriving at only €1 trillion – but roughly the same level of equity. This implies that its leverage would be halved if judged under the US accounting system (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Deutsche Bank results: IFRS vs GAAP

Source: Ackermann (2009)

The key difference between IFRS and GAAP is the treatment of the item called (under IFRS) “positive market values from derivatives”, which equals €1.224 billion on Deutsche Bank’s IFRS balance sheet. Under GAAP, however, this item would shrink to about one-tenth of that figure, with only €128 billion appearing under “derivatives post netting”. A similar observation applies to the liability side of the balance sheet. With IFRS, Deutsche Bank also shows over €1.2 billion in liabilities under “market values of derivatives”, which presumably would also be reduced by a factor of about 10 under GAAP. For other categories (loans, repos, etc.) the difference in the results between IFRS and GAAP are minor.

This important difference in reporting on derivatives, however, renders as meaningless any transatlantic comparisons in leverage for investment banks (or the investment banking arms of EU universal banks) – which is exactly where the crisis arose in 2008. Unfortunately, none of the leading US investment banks have published its accounts under IFRS. Despite this, the notes to the balance sheets of some of them show that the impact of showing the ‘gross’ amount of derivates exposure would be major.

For example, the institution epitomising investment banking, Goldman Sachs, reported at the end of 2008 a balance sheet (total assets) of about $900 billion (equivalent to about €600 billion, which would not put GS among the top five in Europe) with the item “market value of derivatives” amounting to $120 billion. But the notes to its financial statement reveal that the gross derivatives exposure was over $3,700 billion or 30 times more. This suggests that measured under IFRS, the balance sheet might be 5 times larger (3,700 + 900 = 4,600) than under GAAP. Goldman Sachs reported shareholders’ equity of $64 billion for end 2008. This would translate into a leverage ratio of slightly below 15 under GAAP (900/64), but under IFRS the leverage ratio would be five time higher, almost 72 (4,600/64)! This is higher than the IFRS leverage for Deutsche Bank mentioned above and almost three times the average of the 15 largest European banks (see below).

Explaining the difference between IFRS and GAAP

What is the reason for this huge difference in the way derivatives show up in the balance sheet? The key difference is the netting allowed under GAAP, but not IFRS.

In the wake of the market’s reaction to the insolvency of Lehman Brothers, too interconnected has been advocated as another principle for not letting a bank fail. Under IFRS this might not be a separate principle from the usual too big to fail, since most interconnections show up in the balance sheet, but not under GAAP. This difference between IFRS and GAAP could resolve to some extent the mystery of why the US authorities were surprised by the extent of the market reaction to the failure of Lehman. Lehman’s balance sheet (total assets around $600 billion, not far from Goldman Sachs) reflected GAAP and thus did not show the extent of the exposure of other market participants. The example from Goldman Sachs suggests that the balance sheet of Lehman under IFRS would have been several times larger, thus giving a better picture of the importance of Lehman. A balance sheet under IFRS would thus give a better picture of the exposure of the bank itself to counterparty risk. Assume a bank has a large amount of derivatives contracts outstanding, but without any significant net exposure. It could still make very large losses in case important counterparties fail and netting arrangements do not work or the pricing of the contracts is distorted, as happens typically in a systemic crisis. This is why the highly leveraged European banks came under such intensive pressure during the acute phase of the crisis.

High leverage should be a warning

Unfortunately, there has been no reduction in leverage since the “Mother of all bailouts” of the autumn of 2008 (see Gros and Micossi 2008).

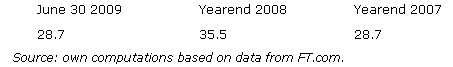

As Table 1 below shows the average leverage ratio of the 15 largest EU banks is exactly at the same level (28.7) as in late 2007, before the crisis. Measured leverage increased temporarily to 35 during the crisis because the increase in volatility increased the value of most derivates. The fact that leverage is still at the same level as at the peak of the credit bubble should be seen as a warning. Should disorderly market conditions return, European policymakers could be faced with similar problems. It is likely that in the US leverage has also not declined if one takes into account “off balance” derivative exposure, but this is not possible to document at this stage.

Table 1. Leverage ratio (total assets/equity), average 15 biggest EU banks

In favour of full disclosure

Regulators have also recently expressed their support for fully recording derivate exposure on balance sheets in a recent consultative document of the Basel Committee.

“213. Certain differences in accounting treatments across jurisdictions can have a significant impact on the measurement of a leverage ratio at an international level. The main difference in accounting between IFRS and GAAP arises from the netting of derivatives and repos.

215. Consistent with taking a non-risk based approach and international comparability the proposed measure of exposure does not permit netting.”

This crisis has shown that a full (gross) accounting for all potential exposure, including derivatives, is essential for two reasons:

- Showing gross derivatives exposure on the balance sheet gives an immediate picture of the interconnectedness of a bank, making it unnecessary to introduce “too interconnected to fail” as an additional criterion.

- An overall leverage ratio based on derivates measured on a gross basis shows the overall exposure of a bank, especially in a systemic crisis. By contrast, the GAAP (and the usual Basel ratios) just show risk under normal market conditions.

References

•Ackermann, Josef (2009), “Financial Transparency”, presentation, Montreal and Toronto, 19-20 February.

•Gros, Daniel and Stefano Micossi (2008), “The beginning of the end game”, VoxEU.org, 20 September.

![]()

Leave a Reply