To recast Mark Twain’s famous quote, the death of the dollar has been greatly exaggerated.

Despite all the hand-wringing over “money printing,” the old greenback surged in Q3. What it means for you and your portfolio is the subject of today’s alert.

First, let me frame the rally, which has been historic.

The U.S. dollar index measures the dollar against a basket of currencies such as the euro and the yen. It was up 7.7% in the third quarter. Outside of the third quarter of 2008 — when the financial crisis was in full fury and the dollar was a favorite safe haven — you have to roll back to 1992 to find a quarterly gain bigger than the one we just saw.

That strength continued into the fourth quarter as the dollar index notched its 12th consecutive weekly gain — the longest on record (which goes back to 1973).

One effect of the strong dollar seems to be a lower gold price. Gold hit its lowest point in 2014 last week. It’s down for the year. This is after falling 28% last year. Gold hasn’t been this low since the middle of 2010.

I’ll just say that if I saw a stock go down for 44 years, I wouldn’t draw the conclusion that it will go up.

I don’t have a strong opinion on gold. It could go to $800. It could go to $2,000. I don’t know. But I don’t think fear of “money printing” is a good reason to own gold. There’s been a lot of money printing going on since 1980. Yet the price of gold would have to get over $2,000 an ounce just to match its 1980 price in inflation-adjusted terms. That’s 34 years and counting of not keeping up with inflation.

Even if you think that start date is unfair — since 1980 was a peak for gold — it doesn’t get better if you roll back further. According to an article at Zero Hedge, gold was $35 an ounce in 1970… and would have to be priced at over $4,000 an ounce just to equal its 1970 purchasing power. That’s 44 years of losing.

Of course, Zero Hedge uses this as a reason to be bullish. The implication being that it will get to its inflation-adjusted high. But there is no reason gold has to do so. It might, it might not. I’ll just say that if I saw a stock go down for 44 years, I wouldn’t draw the conclusion that it will go up.

Commodities in general will have a tough time in the face of a strong dollar. We’ve seen this with oil, which has its own supply and demand dynamics acting unfavorably on prices. (That’s a fancy way of saying there is too much oil.)

Even so, commodity producers can be a good bet even if the commodity goes nowhere. And you are patient. Consider the energy sector.

The sell-off in energy names in the last few weeks has been something to behold. Here I think there is good value. I recently spoke with David Neuhauser at Livermore Partners, who gave us two bargains: Zargon Oil & Gas and Long Run Exploration. These are cash-spinning assets even at lower oil prices. Both pay around 10%. I’ve spoken with David recently, and he’s still buying both.

And two weeks ago, I was up in Sprott’s office talking to Steve Yuzpe. He heads up Sprott’s publicly listed private equity firm, called Sprott Resource Corp. Steve recently bought a producer of met coal called Corsa Coal. (It trades in Toronto.) Met coal prices are down 50% in the last few years. But clearly, some companies can still make good money at today’s prices (or even lower prices). Yuzpe thinks Corsa is one of them.

As for stocks more generally, it’s hard to say what a strong dollar means. Ben Levisohn’s column in Barron’s over the weekend pointed out that it doesn’t mean stocks have to go down:

“From June 1995 to June 2001, the greenback soared 46%, propelled by a booming economy, while the S&P 500 more than doubled. The dollar also surged 78% from June 1980 to December 1984 as Fed Chief Paul Volcker, who was trying to kill inflation once and for all, hiked short-term rates so high they got altitude sickness. The S&P 500 gained 46% in that stretch.”

The market doesn’t care about history, though. The S&P 500, a proxy for the U.S. stock market, is full of multinational companies that get significant earnings from overseas operations. With the dollar taking a big jump, the value of those earnings falls. It also makes their goods more expensive to overseas buyers.

So expect a ding to the earnings of U.S. companies selling stuff overseas. But since this market doesn’t seem to care about earnings, maybe it won’t matter. (I’m joking. I think it could be an ugly quarter when earnings roll in. We’ll see.)

What I really think is that you should not worry much about the U.S. dollar’s strength or weakness. This is not to say it doesn’t have effects. Of course it does. I say you shouldn’t worry about it because you can’t predict what’s going to happen next.

The dollar is strong, for now. How long it is is anybody’s guess.

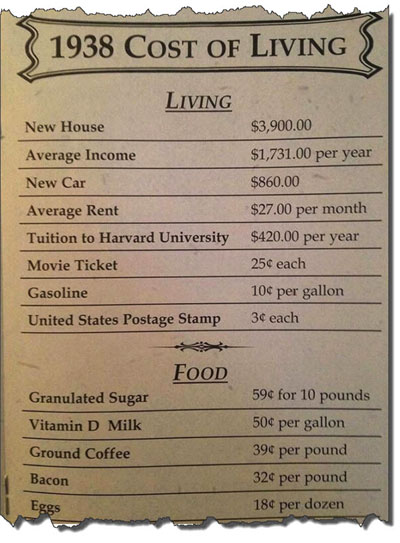

In any case, the long-term bet is that the dollar will, in general, buy less in the future than it can today. I share here a graphic from Zero Hedge:

It’s safe to say we can all share such stories. (“Golly, I remember when…”) And our children and grandchildren will have their own such tales to tell.

I spend most of my time looking for good value in names that can create wealth for us in a variety of scenarios over time. Ideally, these would be rich in catalysts — such as a potential spinoff or buyout — that will make things happen. That’s where my focus is.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply