The euro has appreciated sharply since July 2012. This column introduces a CEPR Policy Insight which argues that the strong euro is not the result of a ‘currency war’. The Eurozone suffers from an overly restrictive monetary policy. The sooner the ECB adopts a more aggressive monetary stance, the sooner the recovery will take hold. Easier Eurozone monetary conditions will lead to a temporarily depreciated euro, which will support aggregate economic activity and help inflation stay close to 2%.

Since July 2012, the euro appreciated more than 10% against the dollar, 6% against the pound sterling, and almost 50% against the yen (IMF 2014). Does this mean that the euro a casualty of a ‘currency war’? We believe the answer is ‘no’. The strength of the euro is the result of an overly restrictive monetary policy by the ECB.

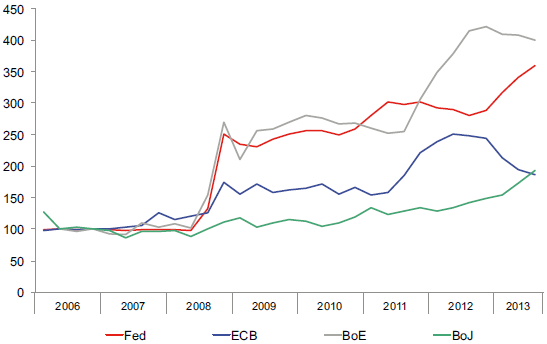

- Since July 2012, the Fed, the Bank of England (BoE) and the Bank of Japan have carried out aggressively expansionary monetary policies – mostly via balance-sheet expansion (quantitative easing).

- The Fed and the BoE have forward-guidance policies with explicit thresholds, with the aim of lowering medium-run interest rates.

- By contrast, the ECB has conducted a ‘passive’ contractionary policy, its balance sheet contracting significantly as a result of early repayments of long-term refinancing operations (Figure 1).

The ECB has also not followed explicit forward-guidance criteria.

This alignment of policies clearly has exchange-rate implications. The impact of quantitative easing on exchange rates has been confirmed for instance by Neely (2011). Thus, the appreciation of the euro results from the contrasted evolution of monetary policy in the Eurozone and the rest of the world, on the top of reduced perceived risk of a breakup of the Eurozone.

Figure 1. Total assets of four central banks in % of GDP, base 100 in 2006Q2

Source: Central banks.

ECB money policy is too tight

In our recent research, we argue that monetary policy in the Eurozone is excessively tight (Bénassy-Quéré, Gourinchas, Martin and Plantin 2014). For instance:

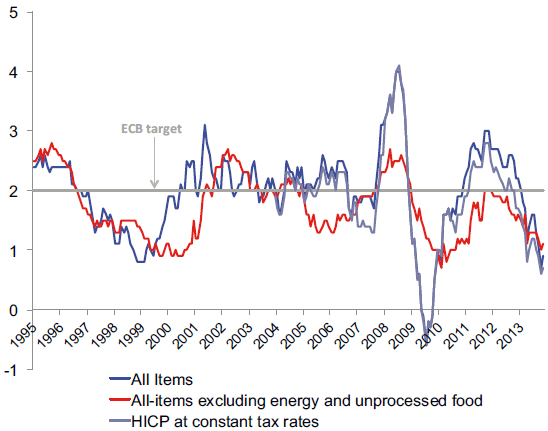

- Eurozone inflation is dangerously low at just 0.7% (Figure 2).

Although inflation expectations are “well-anchored, below but close to 2%”, every month that passes with an inflation rate close to 1% or even below raises the risk that more EZ members will slip into deflation. It also makes the adjustment of relative prices and the benefits from structural reforms correspondingly more difficult to achieve in peripheral countries already heavily burdened by high debt levels.

- The unemployment rate of the Eurozone is above 12%;

- Credit markets continue their downward trend; and

- The transmission of monetary policy to different member countries remains extremely fragmented.

We believe that a further monetary expansion is a necessity, given the ECB’s mandate and the tools currently at its disposal. Such an expansion could take the following form:

Figure 2. Inflation rates, year-on-year change, in %

Source: ECB.

- The direct purchase by the ECB of securitised small and medium enterprises (SME) loans would, in our view, be the most effective instrument.

It would help overcome the fragmentation of Eurozone financing conditions. The direct purchase of securities by the central bank offers two advantages. It is aimed directly at SME credit, which remains very restricted in peripheral countries. It also eases banks’ equity constraints, not just their liquidity constraints, by removing assets with high risk weights from the banks’ balance sheets. We view these equity capital constraints as the main obstacle to the transmission of monetary policy in peripheral countries, such as Italy.

- In order to secure bank liquidity in the long term, the ECB could offer a new VLTRO-type refinancing scheme with a longer maturity, such as five years, for example.

A fixed rate over five years would offer maximum visibility for borrowing banks. It would also significantly expose the ECB to the risk of a future rise in interest rates. The ECB could, however, limit this risk by reserving the right to review the rate, within certain limits, after three years.

In order to reduce the deleterious feedback look between sovereign risk and banking risk, we propose to restrict the collateral eligible for this facility to securities backed by credit to the private sector. Such an approach would likely lead to a significant increase in the ECB’s balance sheet whilst respecting the economy’s financing profile in the zone, which remains bank credit;

- Finally, with regards to forward guidance, we propose that the ECB commit to implementing unconventional policies such as those outlined above, as long as a given measurement of medium-term inflation in the Eurozone remains below a given threshold.

A temporarily weaker euro

Any debate on potential exchange-rate misalignments is plagued with the difficulty of estimating the appropriate level of exchange rates at a given point in time. The discussion on the value of the euro is a perfect illustration of this ambiguity.

- On the one hand, the real effective exchange rate of the euro today is not very far from its long-term average.

The fact that the Eurozone displays a growing current-account surplus is also consistent with the view that the euro is not currently excessively overvalued.

- On the other hand, the previous analysis suggests that the ECB’s policy has become excessively restrictive.

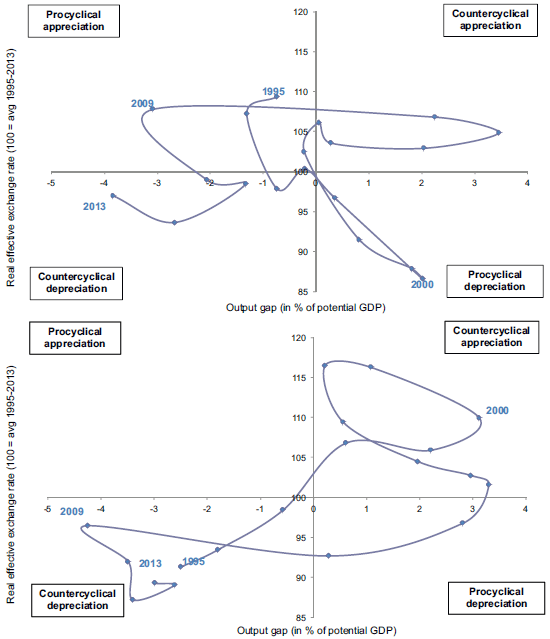

If, as we recommend, it is relaxed further, the euro would depreciate, albeit temporarily. This temporary depreciation would further support aggregate economic activity in the Eurozone. This view is reinforced by the observation that, over the 1995–2013 period, the euro has often evolved in a perverse procyclical way (appreciating when the economy is weak and depreciating when the economy is booming), in contrast with the dollar (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The real effective exchange rate over the production cycle

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 2013–2.

What are the benefits of a weaker euro?

How would a weaker euro help aggregate activity in the Eurozone? The conventional response to this question is that a weaker euro would temporarily boost Eurozone exports, which would more than counterbalance the negative impact of the depreciation on households’ purchasing power. We use new estimates by Héricourt, Martin and Orefice (2014) of the effects of the euro on French exporters based on firm level customs data for the 1995–2010 period.

- The evidence suggests that, other things equal, a 10% depreciation in the euro against a non-Eurozone partner country increases the value of the average French exporter’s sales to this country by around 5–6%.

This increase – the major part of which obtains in the year of the depreciation – stems primarily from an increase in volumes (4–5%), with the remainder (0.5–1%) from an increase in mark-ups. A 10% appreciation in the euro has a symmetrical impact, with the value of exports reduced by an average of 5–6% for the average French exporting firm.

In aggregate terms, we find that the impact of a 10% depreciation in the euro on the value of exports is larger, at around 7–8%, since the depreciation not only improves the situation of firms already exporting but also paves the way for new firms to enter export markets.

These effects are quantitatively significant; with French exports outside of the Eurozone accounting for 11% of GDP, a 10% depreciation in the euro against the currencies of all non-Eurozone trade partners would have a positive impact on aggregate demand around 0.7% of GDP. This does not imply that French GDP would increase by 0.7% since the analysis does not take into account the effects of the depreciation on imports of manufactured goods (which we find increase by around 3.5% in value for a 10% depreciation), nor on imports of energy and raw materials, nor on purchasing power, consumption, employment, wages, etc. According to the French Mésange macro-econometric model, a 10% depreciation in the euro would result in a 0.6% increase in French GDP after one year and a 1% increase after two years (see French Treasury 2013).

We find no significant difference in terms of sensitivity across major manufacturing sectors. The main export industries (chemistry, automotive, food processing, aeronautics, etc.) in particular are very close to the French average. French exports to OECD countries, on the other hand, are more sensitive to exchange-rate variations than those to emerging countries. Exports to the US, in particular, increase in value by 9% if the euro depreciates by 10% against the dollar, as is the case for exports to the United Kingdom. This can be explained by the fact that products exported to OECD countries are more similar to, and therefore substitutable with, locally produced goods than exports to emerging countries.

Exporters often convey the message that beyond a certain threshold, a euro appreciation would be particularly harmful to their sales. This suggests that exchange-rate variations potentially have a non-linear impact: small when the euro is close to its equilibrium level, and large when it significantly deviates from this level. In the case of French exporters, we are unable to identify such threshold effects.

Our results confirm that a nominal depreciation in the euro has the same effect on the value of exports as a fall in prices in France relative to foreign prices. This may be good news for President Hollande, who recently announced an ambitious strategy of lowering social contributions in order to curb labour costs and improve French firms’ competitiveness. This strategy may be superior to a euro-depreciation in that it will be longer lasting and affect exports both in and out of the Eurozone. However it will take more time and will be more limited in magnitude than a depreciation of the euro that could easily reach 10 to 20%.

Finally, our analysis shows that, although the temptation is great to try to influence the euro through speeches and public statements, such statements have no impact on the value of the common currency.

Rather than an excessively strong euro, the Eurozone suffers from an overly restrictive monetary policy. The sooner the ECB adopts a more aggressive monetary stance, the sooner the recovery will take hold. Easier Eurozone monetary conditions will lead to a temporarily depreciated euro, which will support aggregate economic activity and help inflation stay close to 2%.

References

•Bénassy-Quéré A, P O Gourinchas, P Martin and G Plantin (2014), “The euro in the ‘currency war’”, CEPR Policy Insight 70.

•French Treasury (Direction générale du Trésor) (2014), Rapport économique, social et financier pour 2014, Part I: 54.

•Héricourt J, P Martin and G Orefice (2014), “Les exportateurs français face aux variations de l’euro”, La Lettre du CEPII 340.

•IMF (2014), World Economic Outlook Update: Is the tide rising?.

•Neely, C J (2011), “The Large-Scale Asset Purchases Had Large International Effects”, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Working Paper 2010-018C.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply