This column suggests it might be. There’s been a recent and significant retreat in European financial integration and a retrenchment of global banking (although capital inflows into emerging markets and FDI are only just below their recent peaks). What are we to make of this shift? A more compartmentalised global financial system could certainly reduce the likelihood of a financial crisis spreading from one country to the next. But there is now a danger that the pendulum could swing too far, Policymakers should therefore do more to remove limitations on FDI and investor purchases of foreign equities and bonds, balancing the trade-off between the need for stability and the need to provide financing for economic growth.

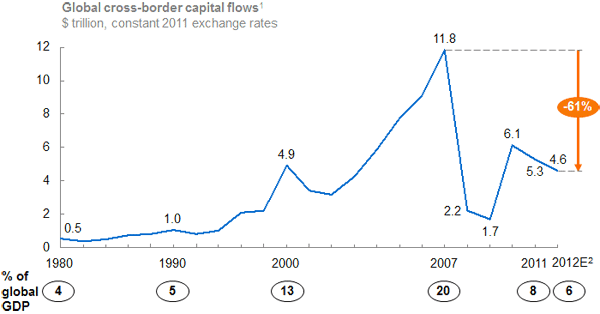

Cross-border capital flows – including foreign direct investment, investor purchases of foreign bonds and equities, and cross-border lending – rose from $0.5 trillion in 1980 to a peak of $11.8 trillion in 2007 as national financial markets grew ever more tightly integrated. Yet when the crisis struck, that intricate web of connections rapidly transmitted shocks between countries confirming that the network of financial interdependencies can cascade risks (Elliott, Golub, and Jackson 2013).

Almost five years after the Crisis, cross-border capital flows remain 60% below their pre-Crisis peak (Figure 1). The question now is the extent to which these trends are a healthy correction, blowing off some of the pre-Crisis froth and resulting in a lower cascade of risks. Or do we face a threat to future growth and prosperity? The answer requires a granular look at the types of flows and countries involved.

Figure 1. Cross-border capital flows fell sharply in 2008 and today remain more than 60% below their pre-Crisis peak

Notes: 1Includes foreign direct investment, purchases of foreign bonds and equities, and cross-border loans and deposits.

2Estimated based on data through the latest available quarter (Q3 for major developed economies, Q2 for other advanced and emerging economies). For countries without quarterly data, we use trends from the Institute of International Finance.

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF) Balance of Payments; Institute of International Finance (IIF); McKinsey Global Institute analysis.

Although the decline in capital flows has been felt globally, there are two primary drivers:

- First, there has been a dramatic reversal of European financial integration.

After the creation of the euro, cross-border lending and investment soared both within the Eurozone and from other countries that sought to tap the single market. Inbound capital flows to the Eurozone grew from $0.5 trillion in 2000 to a peak of $2.2 trillion in 2006, with an estimated 60% coming from other Eurozone countries.

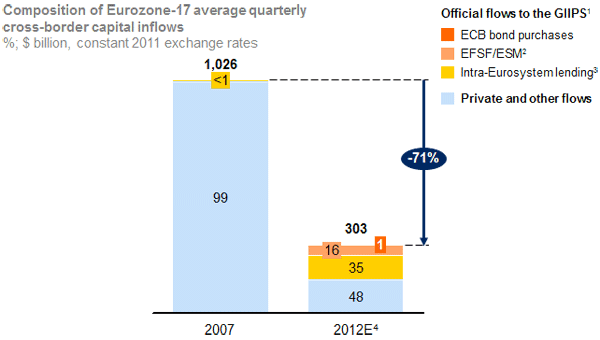

But now European financial integration has gone into reverse. Eurozone banks have reduced cross-border lending and other claims within the Eurozone by $2.8 trillion since the end of 2007 – and this extends far beyond the periphery crisis countries. Central banks and other official sources have sought to fill the dramatic gap in private capital flows in Europe. They represent about half of all capital flowing in the Eurozone (Figure 2). Private capital flows have fallen to just $150 billion in 2012 – an 85% decline from 2007. And in the GIIPS – Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain – private investors have withdrawn on net over $900 billion; central bank and other bail-out funds have been the only net new capital flows.

Figure 2. Central-bank flows now account for 50% of capital flows in the Eurozone

Notes: 1GIIPS comprises Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain; 2European Financial Stability Facility/European Stability Mechanism; 3Measured as changes in TARGET2 liabilities of GIIPS central banks, less the portion associated with EFSF/ESM; 4Calculated based on data up to 3Q12.

Source: Eurostat; individual central banks’ balance sheets; McKinsey Global Institute analysis.

- A second major driver of the decline in global capital flows has been a retrenchment of global banking.

A decline in cross-border lending – both within the Eurozone and beyond – explains half of the global decline. With new capital requirement and regulatory pressures to promote subsidiarisation of foreign operations, the benefits of building a sprawling global footprint are eroding. Global banks are now carefully assessing their foreign operations and exiting those without a clear competitive advantage. Since 2007, banks worldwide have divested at least $722 billion in assets, about half of those foreign. Leaner, nimbler institutions are emerging.

Other types of flows not affected

In contrast, other types of global capital flows have not been hit.

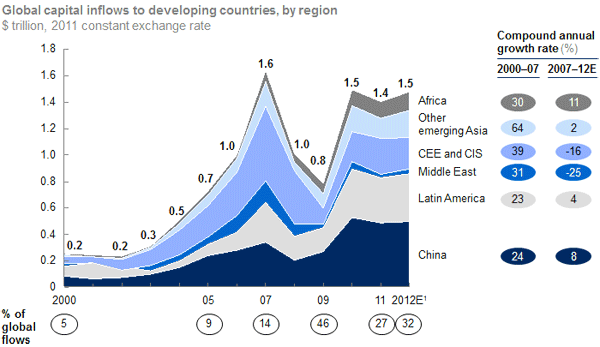

- Capital inflows into emerging markets are near the 2007 peak in most regions as investors see to tap their robust economic growth (Figure 3).

- Foreign direct investment is only fractionally off its peak.

Figure 3. Capital inflows to developing economies totaled $1.5 trillion in 2012 and are near the pre-Crisis peak

Notes: 1Estimated based on data through Q2 2012. For countries without quarterly data, we use trends from the Institute of International Finance.

Source: IMF Balance of Payments; Institute of International Finance; McKinsey Global Institute analysis.

This reflects the fact that such investments reflect long-term strategies by companies to get closer to emerging market customers and to set up global supply chains.

Clearly, some of the frothy excesses of the bubble years have now evaporated. At least some of the retreat of global banks and other investors reflects a more sober approach to investing and a return to longer-term trends.

However, with global banks scaling back cross-border operations, regulators questioning the benefits of cross-border capital flows, and some governments moving to keep capital trapped at home, we could be witnessing the start of a more balkanised global financial system that relies more heavily on domestic capital formation. This could lead to sharp regional differences in the availability and cost of capital, particularly for the smaller businesses and consumers unable to tap the global market, constraining investment and growth in some countries, and at the same time reducing the benefits of diversification for investors.

Implications

It’s true that a more compartmentalised global financial system could reduce the likelihood of a financial crisis spreading from one country to the next. But there is now a danger that the pendulum could swing too far, depressing investment and concentrating risk within domestic banking systems. Tightly restricting the activities of foreign banks and investors also limits the benefits that foreign players can bring to a country: greater access to capital, more competition, new technologies and ideas, and lower costs of borrowing.

Healthy financial globalisation cannot resume without safeguards in place to provide confidence and stability. The regulatory reform initiatives currently under way – working out the final details of Basel III, creating clear processes for cross-border bank resolution and recovery, and building macroprudential supervisory capabilities – will go a long way toward providing that framework. The recent crisis in Cyprus also brought home the need to establish a full European banking union that includes common supervision, resolution mechanisms, and deposit insurance.

But it’s also important for reforms to ensure an adequate flow of financing to the real economy. A large body of academic literature has examined the relationship between financing and economic growth, with most empirical studies finding a positive correlation (Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Levine 2009). The free flow of capital also offers the benefits of global diversification to savers and investors.

That doesn’t have to mean reopening the floodgates of volatile short-term and interbank lending.

Policy messages

A good first step for global policymakers would be removing limitations on foreign direct investment and investor purchases of foreign equities and bonds, which are the most stable types of capital flows (Forbes and Warnock 2012). Many countries restrict the foreign investment positions of their pension funds, and limit the access of foreign investors to local stock markets. Removing these barriers would increase the availability of long-term financing for business expansion (Group of Thirty 2013).

Openness to foreign investment entails trade-offs. Policymakers have to balance the risks of volatility, exchange-rate pressures, and vulnerability to sudden reversals in capital flows against the benefits of wider access to credit and enhanced competition. But it’s important to maintain the larger goal of building a competitive, diverse financial sector. Capital flows do matter – and the challenge is to strike the right policy balance between the need for stability and the need to provide financing for economic growth.

References

•Beck, Thorsten, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, and Ross Levine (2009), “Financial institutions and markets across countries and over time: Data and analysis”, World Bank policy research working paper number 4943, May.

•Beck, Thorsten et al. (2000), “Financial structure and economic development: Firm, industry, and country evidence”, World Bank policy research working paper number 2423, June.

•Cecchetti, Stephen G, and Enisse Kharroubi (2012), “Reassessing the impact of finance on growth”, Bank for International Settlements working paper number 381, July.

•Elliott, Matthew, Benjamin Golub, and Matthew O Jackson (2013), “Financial networks and contagion”, SRREN working paper, January.

•Group of Thirty (2013), “Long-term finance and economic growth”, February.

•Levine, Ross (2005), “Finance and growth: Theory and evidence”, in Philippe Aghion and Steven Durlauf (eds.) Handbook of economic growth 1, Elsevier.

•McKinsey Global Institute (2013), “Financial globalization: Retreat or reset?”, March.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply