What did Mark Twain once remark about his obituary, published in a local newspaper? He said, “The report of my death was an exaggeration.” It’s the same thing with gold.

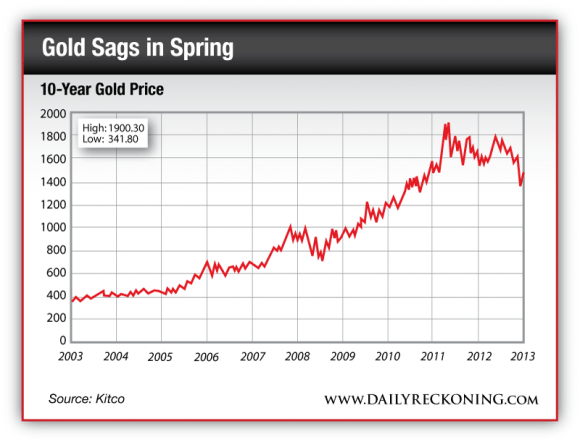

We’ve had a superb, 10-year run for gold pricing. Yet we recently experienced a big sell-down.

Gold’s springtime plunge — what gives?

Media accounts — many from the usual suspects — relate that gold is no longer a safe haven for either wealth protection or long-term gains in the face of global inflation. This line of anti-gold argument seems to have popped up on the screen exactly when investors everywhere seek a safe haven in rough economic seas. Like the man says, be careful what you read in the newspapers.

In a curious twist of fate, while the “paper” price for gold plummeted, buyers everywhere walked into gold shops and souks and walked out with everything they could carry. For example, while many Western investors fixate on the Dow Jones index’s recent climb to 15,000 (whatever THAT means!), Chinese buyers scooped up physical gold literally with both hands.

What’s happening in China reflects what’s happening across the world. Individuals are protecting themselves against an oncoming monetary storm. At the retail level, people are buying gold, and lots of it. From my perspective, it’s a harbinger of things to come, and one of the few times you’ll ever see “small guy” investors take a position ahead of the so-called “Big Money.” That is, usually, the little guy is late to the party. Not now.

The divergence between paper gold and physical metal helps explain what happened with “Big Mining” in recent months.

Gold, silver, copper and base metal miners have all had a tough spring in the share trading pits, losing significant value. It was a smackdown worthy of professional wrestling at its best. What happened?

Well, there’s a strong disconnect between the nominal paper price for gold and personal demand for physical metal. Thus, large institutional money has exited the mining space. That is, gold (and, by extension, gold miners) may be an investment for individuals over the long haul, but in the short term, people who run big, institutional money don’t see it that way. They fail to see what they call “growth” in the sector and head for the exits.

Right now, large money managers, pension funds, hedge funds, etc., are choosing to buy government and corporate bonds, and bond-like equities, rather than gold. Institutional money has taken the Dow Jones index up to 15,000 and more, while walking away from gold, which has been a store of wealth since long before the days of the Roman Empire.

There’s an “apples and oranges” investment issue here. Individual investors can think long term, even over generations. Individuals, however, are not constrained like pension funds, with quarterly performance mandates — for example, “assumptions” of 8% annual returns in a world of Sahara-like overall yields.

Thus, individuals make long-term choices to protect their wealth in gold. Meanwhile, institutions and other Big Money buffaloes follow their herd instinct. Still, whatever the background to it all, it’s a rough time for resource investors in precious metals and the mining space. How does one deal with it?

In general, it’s tough to find a safe parking spot for wealth within the financial system anymore. The marketplace currently favors large, global-scale blue chips — meaning equity investments with wide reach that generate good cash flow and pay bond-like yields.

So what’s wrong with the mining side of things? I’ll dig into that question (so to speak) more below. But first, let’s take a timeout and discuss Apple Computer (NASDAQ:AAPL). Yes, that Apple Computer — the company that makes and sells iPhones, iPads and such.

Unlike most companies that I usually describe, Apple doesn’t drill oil wells or mine copper. The closest Apple comes to being a “resource” play is that its high-tech, heavily engineered products contain smallish quantities of gold, silver, copper and other exotic elements.

So why discuss Apple? Well, I want to slice into Apple’s recent $17 billion bond offering. This is among the largest nonbank bond sales that ever closed. According to Reuters, “Just a week after announcing its first drop in quarterly earnings in a decade, Apple came to market with the massive deal to raise funds for an ambitious program that will return $100 billion in cash to holders of Apple shares.”

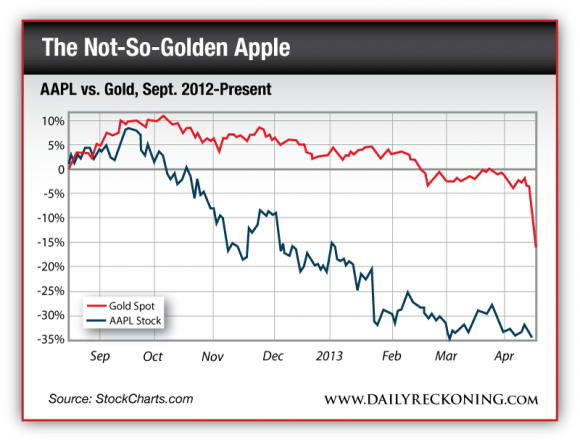

It’s noteworthy that Apple is raising funds on the bond market after a hard spell for its once highflying shares, which have tumbled even more than the price of gold in recent months. Here’s the chart for comparison.

This Apple has been rolling downhill for a long time.

Whatever its share price has been doing, Apple issued a slug of 30-year debt, priced to yield 3.88%, about 1% over U.S. Treasuries. Indeed, when you step back and take it all in, Apple is borrowing money cheaper than most governments. It calls to mind what my Australia-based Daily Reckoning colleague Dan Denning believes about large global firms like Apple — that they’re modern versions of a medieval city-state.

For this modest 3.88% yield from Apple, fixed-income investors swamped the underwriters. Apple’s so-called “six-part, all-dollar offering” was oversubscribed to stratospheric, nosebleed levels, attracting in excess of $50 billion of cumulative orders — nearly $3 on the table for every $1 of Apple paper on offer.

Apparently, Apple reached out and touched investors’ nerves at just the right time for debt, to be sure. That is, despite the above-illustrated share price slide, Apple waltzed into a currently red-hot flow for blue chip bonds. It helps that, whatever its share price, Apple owes — up to now — zero long-term debt. Plus, Apple holds a big wad of raw cash in the U.S. and overseas.

In fact, Apple’s overseas money has created a problem. Much of the money is effectively marooned. Apple can’t repatriate funds to the U.S. without paying a big chunk of tax. So about two-thirds of the new $17 billion of Apple debt is dedicated to paying dividends and repurchasing stock.

In other words, Apple is issuing debt and raising cash in the U.S., backed by a global balance sheet packed with stranded overseas assets. Apple will then pay borrowed funds out as dividends and repurchase shares. By definition, the new debt isn’t going for new investment, such as research and development, new products, new plants, new equipment and such.

Do you recall the idea of Apple as a city-state? Like governments everywhere, Apple is raising money to pay most of it out — give it back, so to speak, to connected stakeholders. Put another way, with this recent bond issue, Apple is engaging in financial engineering, versus electrical or electronic engineering or software engineering. Where’s the ghost of the late Steve Jobs in all this? Is Apple still Apple?

When you come from the mines and minerals side of things — especially when you appreciate gold and silver as long-term stores of wealth — it’s quite peculiar that Apple is issuing 30-year bonds to pay current dividends and buy back stock.

Apple’s borrowed funds aren’t dedicated to investing in “hard” assets or new research into the next generation of products. But looking ahead, say, 30 years — and considering how fast the electronics industry is transforming — would you like to own ingots or apples? Retail investors are buying physical gold across the world, while Big Money is selling miners and buying Apple bonds. Who’s right over the long term? We’ll find out, eventually.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply