Many observers have been baffled by the transformation of Ben Bernanke the academic who argued the Bank of Japan in the 1990s was not trying hard enough to restore aggregate demand to Ben Bernanke the central banker who now seems to be making the same mistakes for which he criticized the the Japanese. This has created numerous discussions over the past few years and now Paul Krugman has a new article on it where nicely coins this phenomenon as the Bernanke Conundrum:

The Bernanke Conundrum — the divergence between what Professor Bernanke advocated and what Chairman Bernanke has actually done — can be reconciled in a few possible ways. Maybe Professor Bernanke was wrong, and there’s nothing more a policy maker in this situation can do. Maybe politics are the impediment, and Chairman Bernanke has been forced to hide his inner professor. Or maybe the onetime academic has been assimilated by the Fed Borg and turned into a conventional central banker. Whichever account you prefer, however, the fact is that the Fed isn’t doing the job many economists expected it to do, and a result is mass suffering for American workers.

My best guess is that the disappointing response of the Bernanke Fed represents the effects of both bullies and the Borg, a combination of political intimidation and the desire to make life easy for the Fed as an institution. Whatever the mix of these motives, the result is clear: faced with an economy still in desperate need of help, the Fed is unwilling to provide that help. And that, unfortunately, makes the Fed part of a broader problem.

One of the key reasons for political intimidation is an inordinate fear of inflation. What these inflation critics miss is that the Fed could actually raise the level of aggregate nominal spending by a meaningful amount without jeopardizing long-run inflation expectations. This is possible if one uses a price level or a NGDP level target that provides a credible nominal anchor. Since the inflation critics seem to miss this point let me again explain it using my preferred approach, a NGDP level target.

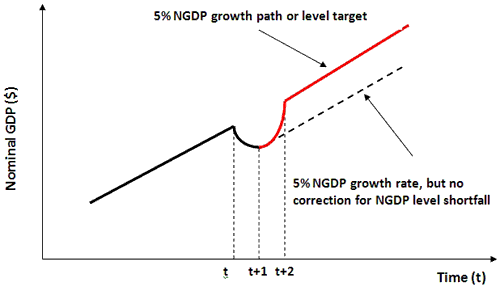

Under a NGDP level target a central bank would commit to keeping aggregate nominal spending on some targeted growth path, say 5%. Such a rule would, therefore, anchor long-run inflation expectations. It would also allow for aggressive catch-up growth (or contraction) in NGDP so that past misses in aggregate nominal spending growth would not cause NGDP to permanently deviate from its targeted growth path. In other words, past NGDP growth mistakes would be corrected. The following figure illustrates this idea:

The black line has NGDP growing at a 5% annualized rate. Then, at time t a negative aggregate demand (AD) shock causes NGDP to contract through time t+1. There is now an a NGDP shortfall. To make up for it, the Fed must actually grow NGDP significantly faster than 5% to return aggregate nominal spending to its targeted level. For example, if NGDP fell 6% between t and t+1 it is now 11% under its trend. Next period the Fed must make up for the 11% shortfall plus the regular 5% growth for that period. In short, the Fed would need to grow NGDP about 16% between t+1 and t+2 to get back to trend. This temporary burst in NGDP would probably make the inflation critics nervous, but they shouldn’t be. There might be temporarily higher inflation as part of the rapid NGDP growth, but over the long-run a NGDP level target would settle back at 5% growth. Nominal expectations would be firmly anchored.

But even then, some higher inflation over the short run would actually be justified. For it would restore nominal incomes to where they were expected to be when debtors and creditors agreed to nominal contracts prior to the the negative AD shock. Similarly, it would return real debt burdens to the path expected when the contracts were first signed. Moreover, the real growth likely to result from the aggressive catch-up NGDP growth would ultimately push up yields giving savers the returns they were expecting before the shock. Remaining on the dashed line, where there is no catch-up growth, would keep yields depressed.

If level targeting was more widely understood I suspect there would be no Bernanke Conundrum.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply