One key question in determining the impact of instability in Libya and elsewhere on world oil markets is how much other countries can and will increase production to offset the shortfall. Here I review the critical role of Saudi Arabia in past disruptions and discuss the current situation.

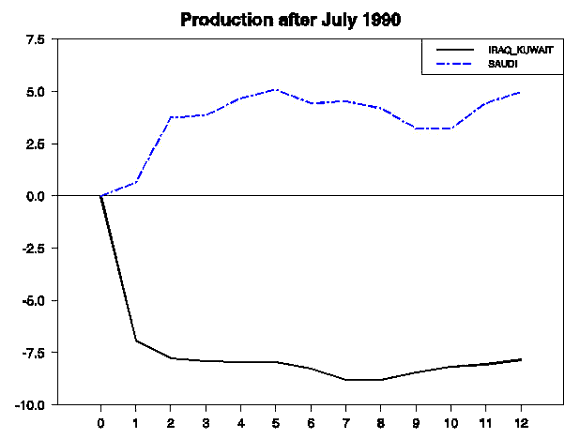

Prior to the First Persian Gulf War in 1990, Iraq and Kuwait between them accounted for almost 9% of world oil production, which was essentially completely knocked out by the military conflict (see the black line in Figure 1). Fortunately, Saudi Arabia had substantial excess capacity, and their increased production amounted to almost 5% of global supplies at the time (blue line). This was a significant factor in limiting the size and duration of the spike in oil prices, and helped mitigate the severity of the 1990-91 economic recession.

Figure 1. Oil production after the first Persian Gulf War. Dashed blue line: change in monthly crude oil production of Saudi Arabia from July 1990 as a percentage of total global production levels in July 1990. Solid black line: change in monthly oil production of Kuwait and Iraq from July 1990 as a percentage of total global production levels in July 1990. Horizontal axis: number of months from July 1990. Data source: EIA.

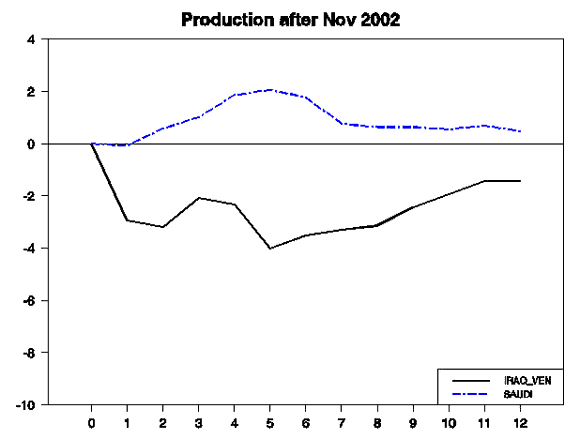

A general strike eliminated 2.1 million barrels per day of oil production from Venezuela in December of 2002 and January of 2003. Shortly after, the Second Persian Gulf War disrupted a similar amount of Iraqi production, with the two combined creating up to a 4% shortfall at the low point (black line in Figure 2). Once again, increases in production from Saudi Arabia (blue line) were an important mitigating factor.

Figure 2. Oil production after the Venezuelan unrest and the second Persian Gulf War. Dashed blue line: change in monthly crude oil production of Saudi Arabia from November 2002 as a percentage of total global production levels in November 2002. Solid black line: change in monthly oil production of Venezuela and Iraq from November 2002 as a percentage of total global production levels in November 2002. Horizontal axis: number of months from November 2002. Data source: EIA.

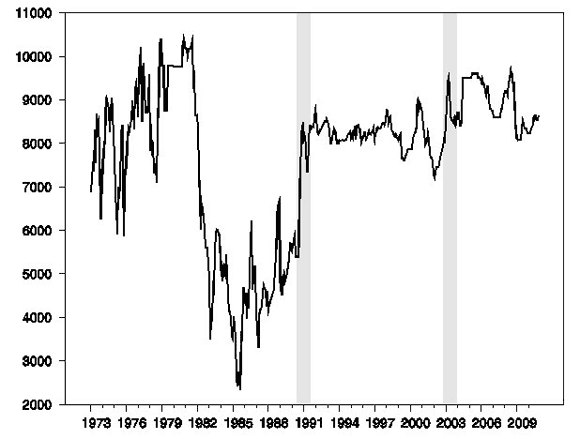

Figure 3 details Saudi production going back to 1973, with the two episodes highlighted above denoted as shaded regions. Throughout most of this period, the Saudis had been a force stabilizing oil prices, dropping production in an effort to moderate the price reductions in the 1980s, and increasing production in episodes like the two mentioned above.

Figure 3. Saudi crude oil production, in thousands of barrels per day, 1973:M1 to 2010:M11. First shaded region represents the episode summarized in Figure 1 (1990:M7 to 1991:M7). Second shaded region represents the episode summarized in Figure 2 (2002:M11 to 2003:M11). Data source: EIA.

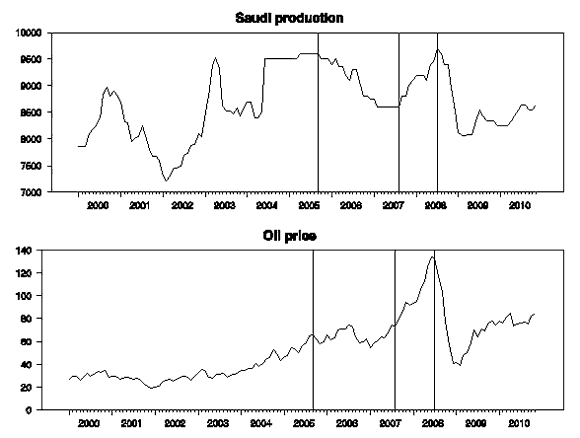

But Saudi oil production looks quite different over the last few years, as highlighted in more detail in Figure 4. The kingdom’s production actually declined between 2005 and 2007. Although it subsequently increased, at the peak of oil prices in July of 2008 Saudi production was essentially only back to where it had been in 2005. The failure of Saudi production to increase between 2005 and 2008 in the face of booming demand for oil from the newly industrialized economies was in my opinion a key reason for the dramatic increase in oil prices over that period.

Figure 4. Top panel: Saudi crude oil production, in thousands of barrels per day, 2000:M1 to 2010:M11, from EIA. Bottom panel: price of West Texas Intermediate, from FRED. Grid lines at 2005:M9, 2007:M8, and 2008:M7.

Subsequent to the 2008 peak in oil prices, the Saudis cut production, consistent with their historical role of moderating the extent of price declines. Saudi Oil Minister Ali al-Naimi claims that the kingdom currently has 3.5 mb/d excess capacity, though many analysts have expressed doubts about those claims.

An increase of a million barrels per day in Saudi production relative to reported November levels, some of which may have in fact already been implemented, would put them back up to where they were in July of 2008. If all of Libyan production gets knocked out, we’d need 1.8 mb/d to replace it. If the Saudis weren’t able or willing to go above those production levels in 2008 when oil was selling for over $140 a barrel, why would you expect them to do so now with West Texas only at $106?

My answer is, I don’t.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply