Years ago, I won a History Book of the Month Club contest by identifying some parliamentary lore from the 19th century House. Back then, filling one’s head with obscure congressional procedures was worth something. Today, with the “Hastert Rule” rolling off the tongues of Washington journalists and TV personalities alike, who needs congressional junkies?

Political science navel-gazing aside, there’s been some good discussion this week (for example, here, here and here) on violations of the so-called Hastert Rule. As many legislative scholars have long argued, the Hastert Rule is better thought of as a behavioral norm than a formal rule: At least since the early 1980s, House leaders have used their leverage over the floor agenda to keep measures off the floor that might divide the majority party. Speakers have been expected to pursue measures that command the support of a majority of the majority party. Former Speaker Denny Hastert recently made plain the costs of allowing the majority to be rolled:

Maybe you can do it once, maybe you can do it twice, but when start making deals when you have to get democrats to pass the legislation, you are not in power anymore…When you start passing stuff that your members are not in line with, all of a sudden your ability to lead is in jeopardy because somebody else is making decisions.

But as John Feehery (Hastert’s aide who coined the “Hastert Rule” label) noted this week, the unwillingness of the far right of the conference to countenance compromise leaves Speaker Boehner with few alternatives: “Boehner has no choice but to vote with Democrats” on must-pass legislation. House conservatives, no doubt seeing the writing on the wall, this week launched two letter campaigns on immigration and gun control, threatening the speaker not to bring any measures to the floor without the support of a majority of the conference.

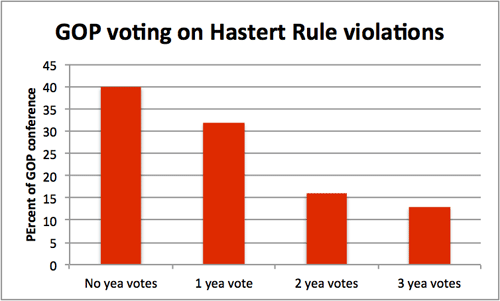

I think it’s worth pausing for a moment to take a closer look at GOP voting behavior on each of the three majority rolls this Congress. The following graph shows the percentage of the GOP conference voting with the Democrats on each of the Hastert rule violations:

First, note that less than fifteen percent of Republicans defected from the party to vote with the Democrats all three times. I suspect the small set of GOP reflects in part the diverse nature of the three votes: Hurricane Sandy relief attracted a regional coalition, the violence against women bill drew moderates, and the battlefield preservation bill accrued support from across the party (and no doubt from War of 1812 re-enactors). There might also be pressure within the conference to limit how often one defects from the majority position, leading to the small set of Hastert rule violators. And of course, the universe of GOP who actually want to vote like a Democrat is particularly small. Less than two dozen GOP serve in districts won by Obama in 2012, and roughly half of them sided with the Democrats on all three votes.

Second, compare the percentage of GOP always voting with the majority of the conference on the three rolls to the percentage of GOP who voted at least once with the Democrats: Roughly forty percent of the conference never crossed the aisle, while just under sixty percent voted at least once (or twice or three times) with the Democrats. A majority of the majority might in fact support the Speaker’s willingness to loosen the Hastert rule. Instead of compromising the Speaker’s authority, bending the rule might bolster it. So long as 218 GOP can’t find common ground on salient measures—and can’t count on Democrats to vote for conservatives’ proposals—Boehner might continue to afford his rank and file the chance to cross the aisle in pursuit of their policy and political goals.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply