Via Mark Thoma, Robin Harding at the FT Money Supply blog reports on a speech given by Bank of Japan Governor Masaaki Shirakawa. The speech reportedly details the problems that emerge from aggressive monetary policy. I cannot find a link to the speech itself, but luckily the FT quotes key sections.

The first concern is two-fold:

Mr Shirakawa’s first point is that loose monetary policy mitigates the pain as households repair their balance sheets, but reduces their incentive to do so quickly, not just for the private sector but for governments as well. However, he also suggests that the effectiveness of loose policy may fall over time as households that weren’t damaged by the crisis bring forward such spending as they want to.

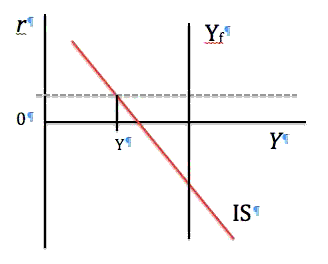

The first sentence sounds like a rehashing of the “liquidationist” approach. We should let the economy collapse rather than provide support during balance sheet adjustment. The second part suggests that there is only so much spending that can be brought forward via low interest rates. But I think this is not really a novel idea, as we pretty much know that the effectiveness of monetary policy fades at the zero bound:

In this case, I drew the LM curve as a (dotted) horizontal line at a positive zero interest rate, suggesting an economy at the zero nominal bound with deflation. Yes, the effectiveness of low interest rates waned as the zero bound was a approached. At this point, if the BoJ wanted to induce additional spending, they would need to make a credible commitment to a higher inflation target. In other words, the effectiveness of monetary policy did not fade unexpectedly – it is exactly what you would expect given the zero bound problem.

The second concern is that a low interest rate environment is hurting potential growth. This time, Shirakawa:

“If low interest rates induce investment projects that are only profitable at such interest rate levels, this could have an adverse impact on productivity and growth potential of the economy by making resource allocation inefficient. While central banks have typically conducted monetary policy by treating a potential growth rate as exogenously given, when the economy is under prolonged shocks arising from balance-sheet repair, we may have to take into account the risk that a continuation of low interest rates will affect the productivity of the overall economy and lower the potential growth rate endogenously.”

I don’t think this makes any sense at all (neither does Harding). I could see a problem if low productivity projects are funded instead of high productivity projects, but presumably the latter would still be funded first in any event. In other words, I don’t see that the low interest rate environment by itself would alter the composition of investment. And if we cut off funding for the less productive investments, the capital stock would grow more slowly, and that would certainly reduce potential growth. And note that this is separate from the worry that government investment is displacing private investment. Government investment is compensating for the lack of private investment. If anything, Japan needs lower real interest rates to support higher levels of private investment to lessen its dependence on fiscal deficits. And that too is another result of the zero bound problem.

The third concern is aptly handled by Harding:

Point three is the more standard argument that flattening the yield curve too far for too long will undermine the profitability of the financial sector.

Again, while I am sympathetic to the financial market consequences of low interest rate environments, the central bank is really just following the economy down. In the absence of sufficient economic activity to pull longer term rates up, if the Bank of Japan raised rates they would simply be inverting the yield curve – and I don’t see that as positive for the financial sector.

The final concern is almost laughable:

“Even though such a rise in commodity prices is affected by globally accommodative monetary conditions, individual central banks recognise that the fluctuation in commodity prices is an exogenous supply shock and focus on core inflation rates which exclude the prices of energy-related items and food. The resulting reluctance of individual central banks to counter rising commodity prices, when aggregated globally, could further boost these prices. From a global perspective, such a situation represents nothing more than a case where a hypothetical “World Central Bank” fails to satisfy the Taylor principle, which ensures the stability of global headline inflation. While it is understandable that the central banks would pursue the stability of their own economies in the conduct of monetary policy, it is increasingly important to take into account the international spillovers and feedback effects on their own economies.”

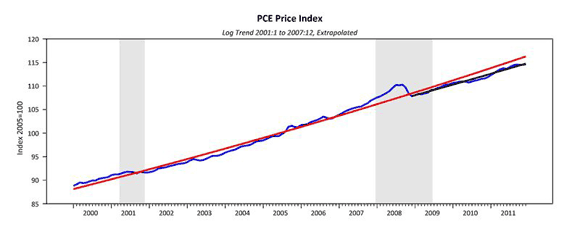

First, Shirakawa is making the error of thinking the Federal Reserve targets core inflation. They do not, and they have made that clear. They target headline inflation, but use core-inflation as a guide as to the direction of headline inflation. Shirakawa implies that while core-inflation is tame, headline is running wild – and that simply is not true:

The path of headline inflation is actually on a lower trend compared to before the recession. Moreover, please explain how headline inflation is causing such a problem for the Bank of Japan:

Finally, as Harding notes, if you don’t like US monetary policy, don’t import it.

Bottom Line: I would be cautious about taking lessons from Shirakawa. The concerns about the low interest rate environment beg the still unanswered question: What is the alternative for monetary policy? To hike short term interest rates? It sounds like Shirakawas “concerns” are more excuses for an ongoing monetary policy failure on the part of the Bank of Japan.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply