If you’re prone to worry about where the economy’s headed, last week’s developments weren’t very reassuring.

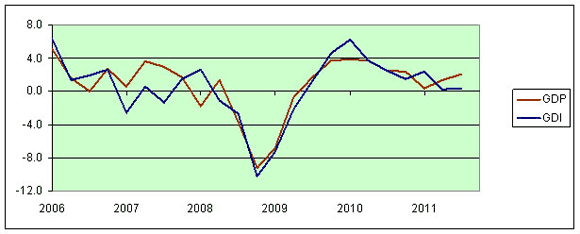

On Tuesday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis revised its estimate of third-quarter real GDP growth down from the initially reported 2.5% annual rate to a new figure of 2.0%. That revision in itself is not particularly scary, since it mostly came from the fact that inventories were drawn down even more than originally estimated– real final sales still grew at a decent 3.6% annual rate for the third quarter. But more troubling is the fact that Tuesday’s figures also gave us the first reading on an alternative measure of third-quarter GDP that is based on a calculation of the total income being earned. This measure, gross domestic income, is conceptually equivalent to GDP but indicated only 0.4% annual real growth for 2011:Q3. Fed economist Jeremy Nalewaik maintains that GDI can give a slightly better early warning of a business cycle turning point. One reasonable procedure is to go with the average of the GDI and GDP growth rates, which gives an anemic 1.2% annual real economic growth rate for the third quarter.

Quarterly growth of real GDP and real GDI, quoted at an annual rate, 2006:Q1-2011:Q3.

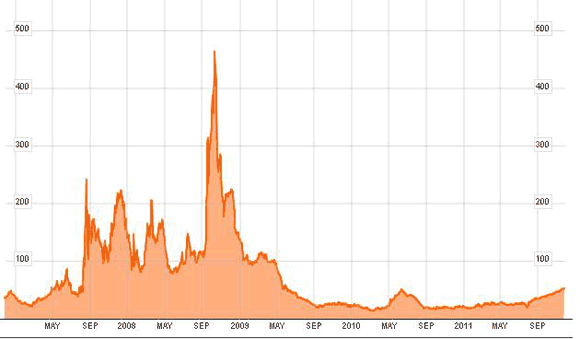

With further inventory declines not anticipated, you might reasonably expect the U.S. growth rate to pick up, if you could ignore the problems brewing in Europe. Problem is, it’s getting pretty hard to ignore those problems. Two weeks after the market briefly cheered Italy’s reforms, the yield on their 10-year government debt is back above 7%.

Yield on Italy government 10-year bonds. Source: Bloomberg.

The Ted spread continues to edge up and is back above 50 basis points. This measures the difference between 3-month Libor (a rate at which banks lend Eurodollars to each other) and the 3-month U.S. T-bill rate. The gap indicates a modest increase in concerns about lending to European banks, though still nowhere near the level in the fall of 2008.

TED spread. Source: Bloomberg.

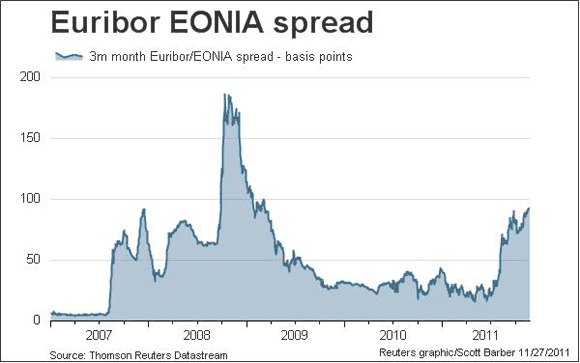

But if a bank wants to borrow in euros rather than Eurodollars, it pays a stiffer premium, as indicated by the spread between the 3-month Euribor and overnight EONIA rates.

Source: Thomson Reuters.

That difference between the euro and Eurodollar risk premium is interesting. One interpretation is that the Fed has done an adequate job of keeping the interbank market liquid, while the ECB has not. Another possibility is that the European bank to which you lend may still be there in 3 months, but the euro itself– who knows?

In any case, the resurgence of spreads on sovereign and interbank debt is an unwelcome development for any global denizen.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply