Italy has one of the worst growth records of any country. Between 1990 and 2010 the U.S economy grew by 63 percent, compared to 19 percent for the Italian economy. Had Italy grown as fast as the U.S, their debt would be manageable.

One cause of slow growth is demographic transformation. During this period Italy’s working age population (those aged 15-64) grew by less than 2 percent, compared to 8 percent in the rest of Western Europe.

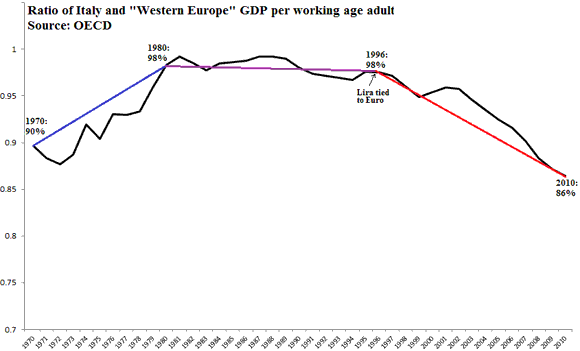

But aging is not Italy’s only problem. In this graph, I have accounted for demographic change by looking at GDP per working age adult, instead of GDP per capita. Italy is compared with the weighted average of the remaining 14 Western European countries.

There are different ways to read the graph, and I don’t want to oversell this interpretation. The hypothesis, not uncommon among Italians, is that Italy started to lag when it joined the Euro and stopped devaluating the Lira. You see, Italy had developed a habit of periodically devaluating its currency to fix whatever cost problem she get herself into. The devaluations lowered the price of Italian exports and jump-started the economy, working as Italy’s “safety valve” (presumably because an internal devaluation through deflation is too hard). The Euro stopped all of this.

Until the early 1980s, Italy was converging to the rest of Europe, as it had done virtually uninterrupted since World War II, during what is referred to as the Italian “miracle”. In 1970 Italy’s output per working age adult was 90 percent of the rest of Western Europe, and ten years later 98 percent, almost fully converged.

Around this point Italy stops converging, but more or less keeps its relative position. In 1996, the year when the Italian Lira is effectively tied to what would soon become the Euro, Italy had the same relative position, 2 percent below the rest of Western Europe. It is after the Euro prevents Italy from devaluating that serious under-performance starts.

There are of course competing explanations, such as Chinese competition or lack of reform, so perhaps the correlation is spurious. You could also put the start of the decline a couple of years earlier. Still, it would not surprise me if Italian growth would re-bound if they leave the Euro.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply