One theme that emerged from the monetary policy conference at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston on Friday and Saturday is that, as I stressed in my discussion of the recent FOMC minutes, the Fed is not thinking of large-scale asset purchases as the only tool available in the current environment.

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans made this quite explicit in his remarks at the conference:

If the Federal Reserve decided to increase the degree of policy accommodation today, two avenues could be: 1) additional large-scale asset purchases, and 2) a communication that policy rates will remain at zero for longer than “an extended period.” A third and complementary policy tool would be to announce that, given the current liquidity trap conditions, monetary policy would seek to target a path for the price level.

Many Fed-watchers understandably focus primarily on the first item since it seems more tangible. But as Evans noted, a prescription for pursuing the third strategy “regularly comes out of careful analyses of mainstream economic models that we use to assess monetary policy options”.

Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke’s comments at the conference also framed large-scale asset purchases as just one element of a broader policy plan. He noted that inflation can be too low as well as too high, and gave the most concrete guidance to date as to exactly how low is too low:

Since the fall of 2007, the Federal Reserve has been publishing the “Summary of Economic Projections” (SEP) four times a year in conjunction with the FOMC minutes. The SEP provides summary statistics and an accompanying narrative regarding the projections of FOMC participants– that is, the Board members and the Reserve Bank presidents–for the growth rate of real gross domestic product (GDP), the unemployment rate, core inflation, and headline inflation over the next several calendar years. Since early 2009, the SEP has also included information about FOMC participants’ longer-run projections for the rates of economic growth, unemployment, and inflation to which the economy is expected to converge over time, in the absence of further shocks and under appropriate monetary policy. Because appropriate monetary policy, by definition, is aimed at achieving the Federal Reserve’s objectives in the longer run, FOMC participants’ longer-run projections for economic growth, unemployment, and inflation may be interpreted, respectively, as estimates of the economy’s longer-run potential growth rate, the longer-run sustainable rate of unemployment, and the mandate-consistent rate of inflation.

In other words, Bernanke is urging us to interpret the SEP longer-run inflation projection as the Fed’s de facto inflation target. And Bernanke also spelled out exactly what this means for anyone who might be slow on the uptake:

The longer-run inflation projections in the SEP indicate that FOMC participants generally judge the mandate-consistent inflation rate to be about 2 percent or a bit below. In contrast, as I noted earlier, recent readings on underlying inflation have been approximately 1 percent. Thus, in effect, inflation is running at rates that are too low relative to the levels that the Committee judges to be most consistent with the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate in the longer run.

We are thus in the historically unprecedented position that for purposes of both its employment and its inflation objectives, the Fed would like to be more accommodative. But what can it do, with short-term interest rates already essentially as low as they can go? Bernanke, like Evans, stressed Fed communication strategies as an alternative or supplement to large-scale asset purchases, though Bernanke noted that either tactic calls for a more comprehensive framework in place for designing and communicating exactly what the Fed is going to do.

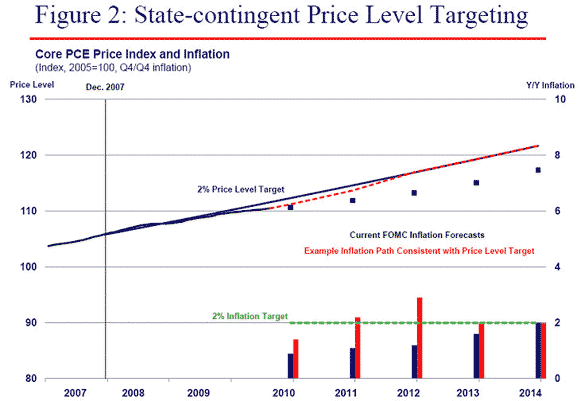

Evans went much farther than Bernanke in proposing details of what such a framework could look like. Evans’ suggestion is to propose a path for the overall price level that would grow at 2% per year, as shown in the solid blue line in the figure below. If a 1% inflation rate for 2010 puts us below that desired path (as indicated by the black box on the graph), the plan would be to aim for a little higher than 2% inflation for 2011 and 2012 (red bars and dashed lines) in order to get back to the target price path.

Source: Evans (2010)

A key aspect of this plan is to

clearly state the terms for the final, state-contingent exit from the P* policy. Determining that the price-level path has been achieved with confidence is a critical determination. Presumably, spending a few months at the price-level path would be more important than simply the first achievement of the path. Once the price-level path is achieved with confidence, the forward-looking monetary policy strategy would return to focusing on 2 percent inflation over the medium term. Future policy misses on either side of 2 percent would be “bygones.” Policy would continue to strive for price stability over the medium term, which would be 2 percent PCE inflation. The past inflation misses would be used to simply inform current analyses of inflation pressures and improve future projections and policy responses.

Although communicating from the beginning what the exit strategy from the price targeting is supposed to be in specific quantitative terms might seem attractive, I worry it could run into a similar embarrassment as the infamous graph of the projected consequences of the economic stimulus package. Even in the best of times, the inflation rate will differ substantially from forecasts and policy objectives. And when the inevitable miss comes, one could imagine that the public would be less rather than more assured as a result of the Fed’s specificity in communication.

My guess is that, although the Fed may be thinking along the lines of a plan like Evans’, the communication will use the kind of language and flexibility displayed in Bernanke’s remarks.

At the Boston conference I also presented my paper with Cynthia Wu on the effects of large-scale asset purchases. Another possible framework for implementing such purchases came up in the discussion of our paper by Larry Meyer (former Fed governor and current managing director of Macroeconomic Advisers) and Joe Gagnon (former Fed officer and current senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics). They both suggested the possibility of targeting a longer-term yield directly, committing to whatever level of LSAP may be necessary to achieve that target. This has some obvious advantages over simply throwing some number of dollars at the market to see what happens. However, it is much trickier to negotiate subsequent changes in the target than is the case with a target for the overnight interest rate. Even when the Fed was targeting the overnight rate, it would sometimes find it impossible to prevent the effective fed funds rate from rising prior to an anticipated increase in the target as banks would try to arbitrage by buying more funds when they were cheaper. The fact that this arbitrage was essentially confined to the two-week reserve maintenance period for which banks were required to hold reserves was the key feature that made targeting the overnight rate manageable as a practical undertaking. Trying to do the same thing with a much longer interest rate is inherently a good deal trickier.

Another strategy would be to use a targeted rate on an intermediate-term security as a more precise way of codifying the “extended period” language. For example, if the Fed really intends to keep the fed funds rate below 25 basis points for the next three years, it could target a 0.25% yield on the 3-year Treasury bond, maintaining the target going forward in the form of a 0.25% target for the 2-year rate one year from today.

A related complication is the fact that the market has already anticipated substantial additional LSAP. My guess is that an additional trillion dollars in purchases is already priced into current bond yields and exchange rates.

For all these reasons, the key message of the November FOMC statement may not be the size of purchases that the Fed announces, but instead the framework it offers as guidance for exactly what such purchases are intended to accomplish.

More than one tool for the Fed

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply