Most observers now seem convinced that the Federal Reserve will shortly implement QE2, a second round of quantitative easing. It’s worth taking a look at what QE2 is and is not expected to accomplish.

The ability of the Federal Reserve to influence what happens in the economy is fundamentally limited. The ultimate power of the Federal Reserve is the ability to create money, and how much money the Fed creates is a key determinant of the purchasing power of an individual dollar bill. A very minimalist position on what the Fed should be doing is that it should aim for a rate of inflation that does not disrupt the economy’s ability to use real resources in the most efficient manner possible.

I think there would be broad agreement that a high and volatile inflation rate does not accomplish that objective. One reason why most of us can agree with that statement is that we have lived through times of high and volatile inflation and know first-hand the kinds of problems that environment can create.

It is also quite clear to me that deflation– an increase in the number of goods you can buy with an individual dollar– can be even more destructive. Since this may be less obvious to many readers, let me review some of the reasons why I say that.

For people struggling under debt burdens, deflation makes repaying the loan more difficult and less likely to happen. If that leads to a wave of bankruptcies, everyone, including creditors, can end up losing out. Debt burdens and delinquencies remain a significant problem holding back the economic recovery today. These problems would magnify enormously if a serious deflation were to get underway.

Deflation also means you can earn a positive rate of return just by stuffing money in your mattress. That creates an incentive for consumers, firms and banks simply to hoard cash rather than invest it productively. Even very sound investments can have a hard time competing for lenders’ dollars when the alternative of hoarding becomes sufficiently lucrative.

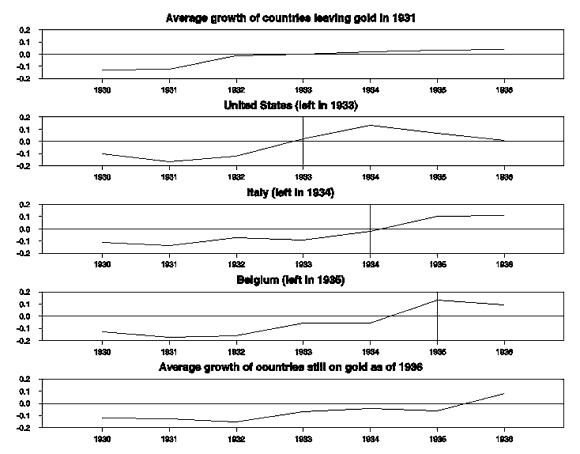

I’m personally persuaded that the 25% drop in the overall price level in the U.S. between 1929 and 1933 was one factor contributing to the depth and severity of the Great Depression. Our recovery began pretty dramatically when the U.S. reflated by dropping parity of the dollar with gold in 1933. Other countries had a similar experience– things began to improve only after prices began rising.

Average real growth rates across different country groups, 1930-1936. Top panel: countries that left the gold standard in 1931. Second panel: growth rates for the U.S., which left the gold standard in 1933. Subsequent panels: countries leaving in 1934, 1935, and still on as of 1936. Source: Bernanke and James (1991).

But even if you agree that significant deflation can be a problem, we’re not seeing deflation in the U.S. at the moment. We had 1% inflation, not deflation, over the last year. What’s the harm in that?

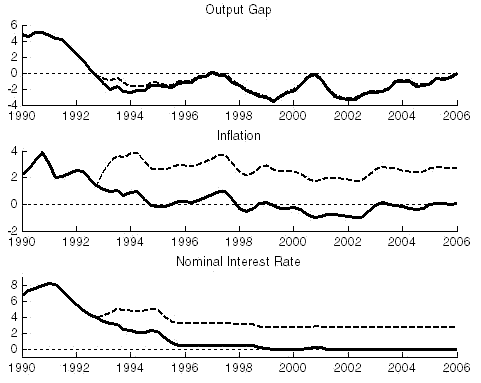

One danger of low inflation is that, if it turns into deflation, the chain reaction can be difficult to stop before significant damage gets done. We’re already at a point where, because of the very low inflation rates, the traditional tool that monetary policy would use to stimulate the economy, lowering the overnight interest rate, has no potency whatever, making it much more difficult for the Fed to arrest a significant deflationary turn should it arise at the moment. And with inflation this low, we’re still seeing some of the problems with debt service and cash hoarding noted above. Many analysts point to Japan’s experience of the 1990s as an illustration of the problems that this kind of low inflation or modest deflationary environment can cultivate.

Actual path (solid line) of output gap, inflation, and interest rate, and simulated counterfactual path (dashes) for Japan,1990-2006. Source: Daniel Leigh (2010).

And even if you don’t agree with me that, given our current economic situation, a 1% inflation rate for the U.S. is destructive, maybe you’d at least agree that, if our inflation rate were to rise to 3%, it wouldn’t be that harmful. On the other hand, there should be no question about the damage being done to people’s lives by the continuing high rates of unemployment and wasted economic capacity. In normal times, we worry about trying to stimulate the economy too much out of concern about the negative consequences of a higher inflation rate. But if the downside for the latter is not that great, why not try to do a little more?

I grant that this is a little like the philosophy of driving your car into the garage until you bump up against the wall. Not generally a good guide for how to drive your car, but at least it is one very reliable way to know that you’ve done all you can. At the moment, I have a great deal of uncertainty, as I think other reasonable observers should as well, as to just how much we could stimulate the economy without producing inflation. I personally believe that we might reach that point sooner than many other analysts seem to be assuming. But the only way to know for sure is to try and see.

I emphasize that more expansion from the Federal Reserve may be of only limited help, and nobody should hope for too much from QE2. I urge the Fed to be carefully watching commodity prices as one indicator of just how far away the wall of the garage may still be.

I do not believe that the Fed can solve our economic problems. But I do believe that excessively low or negative inflation rates will make them worse, and that this is something the Fed can and should prevent.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Wasn’t 2008 to 2009 a deflationary period? Is the CPI really a good measure of inflation? It seems to me that deflation is effectively occurring when interest rates hit zero, which they more or less did during that period.