Last Friday’s consumer price index (CPI) report showed headline inflation in January remaining stable from the previous month at a 2 percent annual rate, a bit above most private forecasts, boosted by higher fuel costs. But the show was stolen by the core measure. Excluding food and energy, consumer inflation saw the largest monthly drop in more than 27 years and its third largest decline in 47 years.

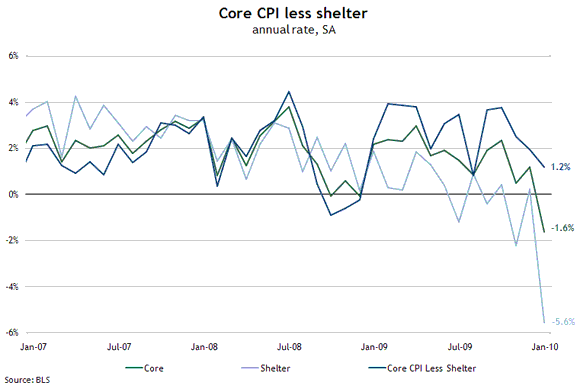

Several factors were behind the decline in the core index (such as falling airline fares, a dip in new car prices, and ongoing declines in prices for household furnishings and operations), but a sizeable drop in shelter prices, which account for more than 40 percent of the core CPI index, was a significant factor in January’s dip. A concern that declining shelter prices could skew the core inflation measure was noted in the minutes of January’s FOMC meeting:

“Though headline inflation had been variable, largely reflecting swings in energy prices, core measures of inflation were subdued and were expected to remain so. One participant noted that core inflation had been held down in recent quarters by unusually slow increases in the price index for shelter, and that the recent behavior of core inflation might be a misleading signal of the underlying inflation trend.”

Chart 1 illustrates the recent decline the in shelter component of the CPI and how, excluding shelter, core inflation has been growing at a more robust pace than is indicated in the overall number.

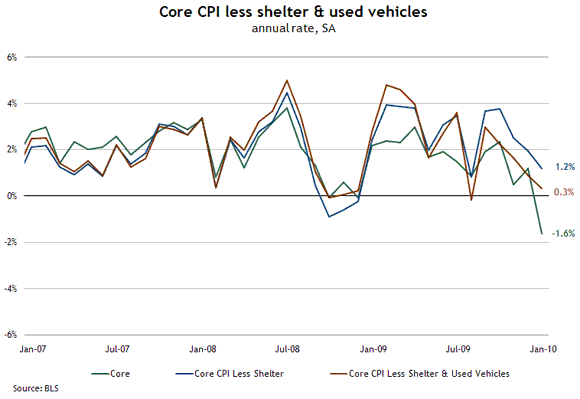

However, once we’ve opened the door for pruning sectors that have displayed unusual price behavior in recent months, we can find a slew of outlying components to pare. Take, for example, vehicle prices. With the impact of the ailing state of U.S. automakers, the federal government’s “Cash for Clunkers” program, and the major recalls from Toyota, auto prices have been particularly volatile lately. Used car and truck prices have grown at annual rates between 20 percent and 44 percent in each of the past six months, skewing, some could argue, the core measure upward.

Chart 2 shows core CPI after subtracting both shelter and used vehicle prices, a picture that shows a lower inflation rate—more in line with the numbers in the overall core CPI.

My point here is not to advocate lopping shelter and vehicles, along with the already excluded food and energy prices from inflation—which, by the way, would leave us with less than 45 percent of the overall CPI index. In fact, my argument is the opposite. There are always some components of the index that seem anomalous—on either side of the distribution. Discriminately cropping entire sectors from the CPI may not be the best method for teasing out true underlying price pressures.

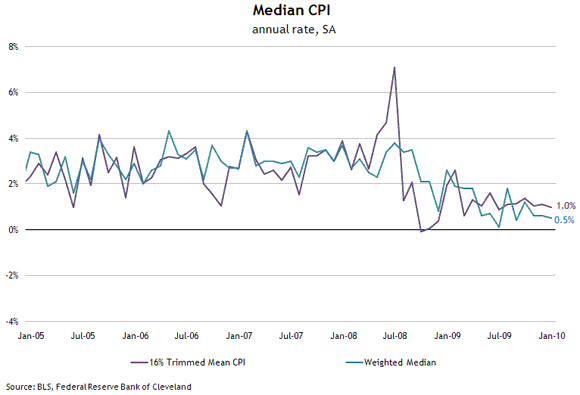

The Cleveland Fed uses a more methodical approach to exclude the CPI components that show the most extreme price changes each month. Their calculations show a more subdued underlying inflation environment, with median and trimmed mean CPI hovering around 1 percent for the past several months (chart 3). I’m not endorsing this method as a perfect estimation of “true” underlying inflation, but it does provide an example of indiscriminately trimming the outliers to see what’s beneath.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply