As Congress gets set in the near future to consider raising the debt ceiling yet again, my fellow blogger L. Randall Wray creatively suggests not raising the debt ceiling but instead having the Treasury continue spending as it always does: by simply crediting bank accounts. As he puts it:

The anti-deficit mania in Washington is getting crazier by the day. So here is what I propose: let’s support Senator Bayh’s proposal to “just say no” to raising the debt ceiling. Once the federal debt reaches $12.1 trillion, the Treasury would be prohibited from selling any more bonds. Treasury would continue to spend by crediting bank accounts of recipients, and reserve accounts of their banks. Banks would offer excess reserves in overnight markets, but would find no takers—hence would have to be content holding reserves and earning whatever rate the Fed wants to pay. But as Chairman Bernanke told Congress, this is no problem because the Fed spends simply by crediting bank accounts.

This would allow Senator Bayh and other deficit warriors to stop worrying about Treasury debt and move on to something important like the loss of millions of jobs.

Wray’s proposal is based upon modern monetary theory (MMT) that is the focus of this blog and those by Bill Mitchell, Warren Mosler, and Winterspeak. Of course, given the lack of understanding of basic reserve accounting at the heart of MMT and Wray’s proposal on the part of the public, the financial press, and the vast majority of economists, one can already anticipate the outpouring of criticism suggesting that such a proposal amounts to “printing money” and thereby destroying the value of the currency. Some probably will even argue that this would put the US on the road to a fate much like Zimbabwe’s (for a good analysis of what’s actually happening in Zimbabwe, see here).

As such, this post considers whether a given deficit resulting in more reserves in circulation and fewer bonds held by the non-government sector raises the likelihood of spiraling inflation, as most interpretations of the government budget constraint (GBC) assume. The approach here recognizes the importance of understanding the balance sheet implications of both of these options that are central to MMT. While most economists typically assume a supply and demand relationship, as in the hypothesized loanable funds market, and then build models accordingly, such an approach can miss important relationships in the real world. In particular, any transaction in a capitalist economy results in changes in the agents’ financial statements; if the hypothesized supply and demand relations are not consistent with the actual changes occurring within the financial statements of the relevant agents, then the hypothesized model is irrelevant. In a modern money regime such as ours in which there is a sovereign currency issuer operating under flexible exchange rates, “monetization” versus “financing” as characterized both in the GBC and in the hypothesized loanable funds market fall into this category.

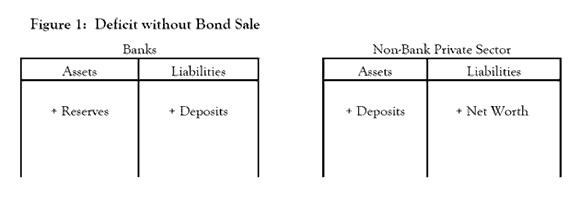

Consider first the case in which the federal government runs a deficit but neither the Treasury nor the Fed sells bonds. This is “monetization” as usually suggested by the GBC. As always, and as noted by Wray, the Treasury spends by crediting bank reserve accounts at the Fed, while simultaneously instructing the banks to credit the deposit accounts of the recipients of the spending. (The process is simply delayed a bit where the Treasury sends the recipient a check, triggered when the recipient deposits the check at his/her bank.) Taxes have the reverse effects. For a government deficit, the Treasury’s credits to accounts are greater than what has been debited via taxation. Figure 1 shows the balance sheet effects of a government deficit for the private sector, with the effects on banks and non-banks shown separately.

As the quantity of reserve balances banks desire to hold to settle payments and meet reserve requirements is already accommodated by the Fed, the deficit in Figure 1 creates excess balances. Prior to fall 2008, Fed operating procedures set the federal funds rate target above the rate paid on reserve balances; in that case, the federal funds target would be bid down—theoretically, to the rate paid on reserve balances. Figure 1—or, “monetization”—thus was not an operational possibility under previous Fed procedures that set the target rate above the rate paid on reserve balances. In other words, prior to fall 2008, even if the federal government wanted to “monetize” the deficit, either the Treasury or the Fed would still have been required to sell bonds to hit the Fed’s target rate. However, since the Fed now sets the target rate equal to the rate paid on reserve balances, no such bond sales by the Fed or the Treasury are necessary. Instead, as the Treasury spends and excess balances increase, the Fed’s target can still be achieved and the Fed can raise or lower its target as desired by simply announcing an equivalent change to both the target rate and the rate paid on reserve balances.

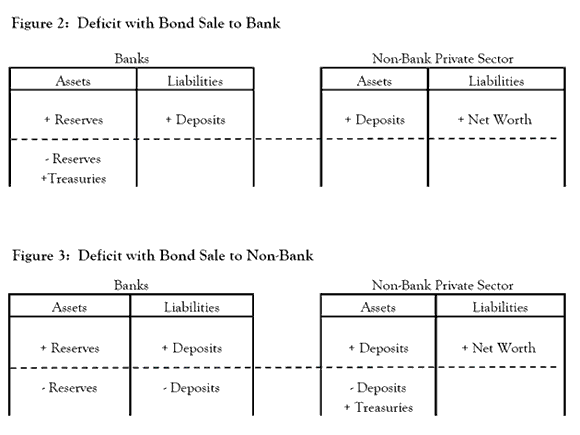

Figures 1 (above), 2 (below), and 3 (below) demonstrate that government deficits create increased net saving in the non-government sector. By definition, additional net saving flows to a given sector are shown on a balance sheet as additional net financial assets and net worth for that sector. The creation of any financial asset generates both an asset and a liability given the two-sided nature of financial assets; in the case of a government deficit, the liability remains on the government’s balance sheet while there is a simultaneous increase in net equity or wealth in the non-government sector.

In Figure 1, the new net financial assets for the non-government sector are the additional deposits—the M1 measure of money—on the non-bank sector’s balance sheet unaccompanied by an offsetting increase in its liabilities.

Figure 2 shows the same deficit accompanied by a bond sale that is purchased by banks. The Treasury security purchase by the banking sector is settled by a debit to reserve accounts. As already explained above, the operational effect of the reserve balance drain is to support the interest rate target under traditional operating procedures. There is still an increase in net financial assets or wealth of the non-government sector, as the deposits (M1) remain on the non-bank private sector’s balance sheet. Figure 3 shows the same deficit accompanied by a bond sale to the non-bank private sector, as in sales to non-bank Treasury dealers. As in Figure 2, the reserve drain enables the Fed to sustain the federal funds rate target under traditional operating procedures, and there are again net financial assets created for the private sector in the form of Treasuries on the non-bank private sector’s balance sheet. (While some may object to the placement of the deficit as the first event and the bond sale as the second event in Figures 2 and 3, note that the ultimate effect on net financial assets is identical regardless of how one orders the transactions.)

In terms of the effect on net financial assets for the non-government sector, the figures show that there is no difference between “monetization” or bond sales besides potential effects on the federal funds rate that depend on the Fed’s chosen method of achieving its target. But from the widely-held view that “monetization” is more inflationary than bond sales, Figure 1 is assumed to be more inflationary than Figures 2 and 3. Regarding Figure 1, though, recall that banks do not use reserve balances or deposits to make loans, as loans CREATE deposits; bank lending or money creation instead occurs when banks are presented with opportunities to lend at an expected profit (and have sufficient capital). Banks instead hold reserve balances ONLY for settling payments and meeting reserve requirements (see, for example, my previous post on bank lending and reserve balances here), and their desired holdings for these purposes are always accommodated by the Fed at its target rate. What this means is that the reserve balance drain shown in Figures 2 or 3 can in no way restrict potential money creation by banks.

Another implication, or (at least) interpretation, of the GBC view and the loanable funds market is that the Treasuries added to the non-bank private sector’s net wealth in Figure 3 are less stimulative than the deposits created in Figure 1. But this is also clearly false, as it ignores the fact that M1 money is left circulating when bonds are sold to banks, as well (as shown in Figure 2), so the distinction to be made in that case is actually between bond sales to the non-bank public and bond sales to banks (i.e., Figures 1 and 2 versus Figure 3) even though to my knowledge no economist has ever suggested that bond sales to banks were more inflationary than bond sales to the non-bank private sector.

Finally, that the non-bank private sector is holding Treasuries rather than deposits in Figure 3 does not somehow constrain its spending. Rather, just as current holders of deposits could choose to convert their new wealth to time deposits instead of spending, individuals holding Treasuries (which are essentially time deposits at the Fed) could opt alternatively to leverage their wealth (and Treasuries happen to be highly valuable as loan collateral). Indeed, whether holding deposits or Treasuries, with greater net wealth and net income flows provided by a government deficit, the non-government sector might logically be more likely to spend than without the deficit while also appearing more creditworthy to banks (who again themselves are never constrained by the quantity of reserve balances or deposits in the amount of lending or money creation they can engage in). In any event, in the presence of a government deficit, spending by the non-government sector is in no plausible way constrained by the fact that it currently might be holding Treasuries instead of deposits.

In sum, whether or not a deficit is accompanied by bond sales is irrelevant for understanding the potential inflationary effects of the deficit. Under normal Fed operating procedures in place until fall 2008, the operational function of bond sales was to support the interest rate target, not to “finance” a deficit. A government bond sale does not somehow reduce funds available for non-government agents to borrow as presumed in the loanable funds market approach, while the absence of a bond sale does not somehow mean there is a greater amount of liquid financial assets, income, or “funds available” for borrowing or spending than without the bond sale. Instead, a government deficit always adds to the non-government sector’s net financial wealth whether or not a bond sale occurs. Both the Treasury’s bond sales and the Fed’s operations affect only the relative quantities of securities, reserve balances, and currency held by the non-government sector; the total sum of these is set by the outstanding government debt. With or without bond sales, it is the non-government sector’s decision to spend or save that matters in regard to the potential inflationary impact of a given government deficit. Indeed, to be more precise, a deficit accompanied by bond sales is actually the MORE potentially inflationary option, as the net financial assets created by the deficit will be increased still further when additional debt service is paid.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Lets just print 12 Trillion dollars and pay off the debt. Then we don’t have to worry about paying interest at all. While you at it just print an other 12 Trillion and pay of every bodies mortgage and then remove all the taxes since we can just print money.

These are the arguments that people have been making for years thinking that somehow the world will go along with this kind of non sense. I guess that is why gold is closing in on 1200 USD because people really like the money printing.

John . . . you’ve completely missed the point. The point is that for a GIVEN deficit, “printing money” isn’t more inflationary than selling bonds. Nowhere here did I suggest anything remotely like what you’ve said. In other words, the debt IS “printing money”; we’ve ALREADY done it (though, by the way, the debt owed to the non-govt is FAR less than $12 trillion).

I give you the 12 Trillion but that was not my point. I also understand that there is not much difference between printing money and offering bonds since the money mostly comes from the same place. But suggesting that we just start printing money is at best irresponsible. That kind of practice will lead to exactly what I described above.

So, do you have a particular place in the post that you can suggest I am incorrect? Or are you just going to do handwaving and say “you’re wrong”?

Printing money isn’t more inflationary than selling bonds.

Lot’s of scams, plans and flim-flams. A torrent of calculations and rationalizations to avoid honest accounting, paying one’s obligations, and actually producing something of worth.

Our Honourable Legislators – by their broken promises shall ye know them. The biggest broken promise is that paper money will keep its value.It is the reward that we all strive for with our life work and education, yet it turns out to be a counterfeit fraud.

Your points are a wrap. No one else seems to understand the breathtaking possibilities of your IORs. IORs aren’t ideal, but they are politically palatable.

Everyone has their favorite way of using the internet. Many of us search to find what we want, click in to a specific website, read what’s available and click out. That’s not necessarily a bad thing because it’s efficient. We learn to tune out things we don’t need and go straight for what’s essential.

This goal-oriented way of surfing the web is largely based on short-term results. For example, finding facts to write a blog post, doing a comparison before making a purchase and reading a news site to find out what’s happening right now.

Dear Scott,

This post was highly unclear. In the figures, it would be helpful to clear the “+reserves” and “- reserves” to zero, if that is what they net to. That would simplify things, clarifying that banks are left without net reserves in the bond cases. While cash reserves are not currently limiting, they would be in more inflationary times.

But the more important point is that spending without bond sales creates net money flow to the private economy, while bond sales create net flow back to the government. While these bonds may be sort of “as good as” money in some forms, as collateral, etc, in the limit case of the government selling infinite treasury bonds and vacuuming out all the money in the economy, one could not very well have inflation, could one?

So they are not equivalent in the final analysis, and it is indeed more inflationary to not balance spending with bonds as to do such balancing. That said, we need a bit of inflation right now, so bond sales are entirely counterproductive tot he macroeconomic policy needed right now.

This post was highly unclear. In the figures, it would be helpful to clear the “+reserves” and “- reserves” to zero, if that is what they net to. That would simplify things, clarifying that banks are left without net reserves in the bond cases.

SORRY FOR ANY CONFUSION. IT’S PRETTY STANDARD FARE IN ACCOUNTING AND T-ACCOUNT ANALYSIS TO DO AS I’VE DONE. ALSO, THE POINT WAS TO SHOW THE ACTUAL ACCOUNTING FOR INDIVIDUAL TRANSACTIONS. THE “NET” IS SO OBVIOUS IT DIDN’T SEEM TO REQUIRE ANYTHING MORE.

While cash reserves are not currently limiting, they would be in more inflationary times.

WRONG. RESERVES ARE NEVER LIMITING EXCEPT FOR IN A GOLD STANDARD OR SIMILAR MONETARY SYSTEM.

But the more important point is that spending without bond sales creates net money flow to the private economy, while bond sales create net flow back to the government.

WRONG. THE BOND SALE IS AN ASSET SWAP, SO NO NET CHANGE. THE DEFICIT CREATES THE NET FLOW TO THE NON-GOVT SECTOR. AGAIN, THIS IS JUST ACCOUNTING 101.

While these bonds may be sort of “as good as” money in some forms, as collateral, etc, in the limit case of the government selling infinite treasury bonds and vacuuming out all the money in the economy, one could not very well have inflation, could one?

THAT DOESN’T MAKE ANY SENSE.

So they are not equivalent in the final analysis, and it is indeed more inflationary to not balance spending with bonds as to do such balancing. That said, we need a bit of inflation right now, so bond sales are entirely counterproductive tot he macroeconomic policy needed right now.

AGAIN, WRONG. THERE’S NO DIFFERENCE IN ANY POSSIBLE SCENARIO UNDER OUR CURRENT MONETARY SYSTEM, EXCEPT THAT BOND SALES ADD INTEREST PAYMENTS AND SO ARE MORE INFLATIONARY, IF ANYTHING. PLEASE SHOW WITH BALANCE SHEETS THE TRANSACTIONS YOU ARE SUGGESTING AS THE REAL WORLD CASE.