Many expect the dollar to continue to depreciate over the foreseeable future. This column suggests that it may strengthen in 2010 if the Federal Reserve exits quantitative easing sooner than its counterparts and the US economy enjoys a strong rebound.

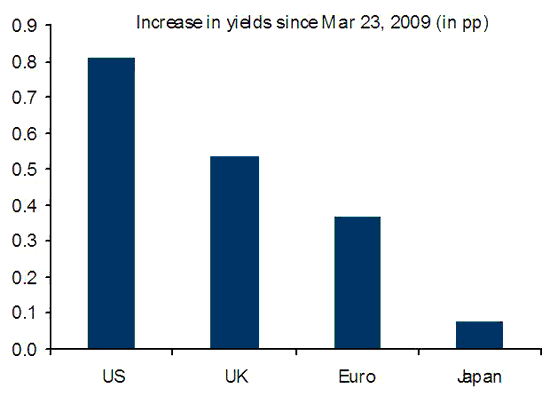

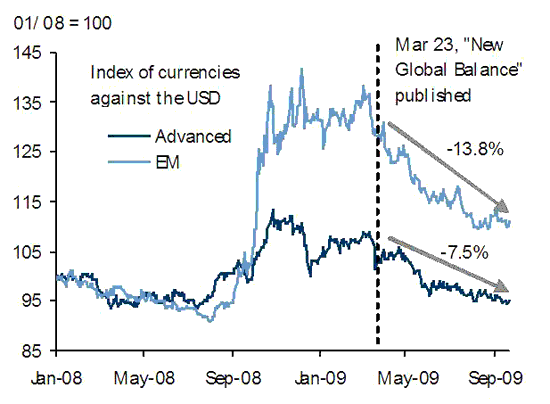

In the early months of the crisis at the end of 2008, the US dollar rose sharply as US interest rates fell sharply (IMF 2009). In a previous column, we argued that the puzzling response of the dollar and US rates during the panic of the fourth quarter of 2008 – stronger dollar and lower rates – would be temporary and that the return of risk appetite and structural aspects of the new global balance – smaller gross capital flows and the savings drain resulting from global fiscal policies – would steepen rates and weaken the dollar. Since the end of March, ten-year US Treasury yields have increased 76bp (to 3.4%), more than in other G7 markets (Figure 1), and a dollar index relative to major currencies indeed weakened 7.5% (13.8% relative to developing countries, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Ten-year yields in the euro area, Japan, UK, and US

Source: Haver, Barclays Capital.

Figure 2. The recent evolution of the dollar

Source: Haver, Barclays Capital.

How will the value of the dollar and long-term interest rates respond in 2010? It seems likely that both US monetary and fiscal policy will join forces to push long-term rates higher when quantitative easing ends. The end of quantitative easing in 2010 and the start of the tightening cycle in the US – both supportive forces for the dollar – should also compensate dollar-negative fiscal considerations. Thus, contrary to the popular view of a continuously weaker dollar, the phasing out of quantitative easing implies that the dollar may strengthen in 2010 relative to other currencies.

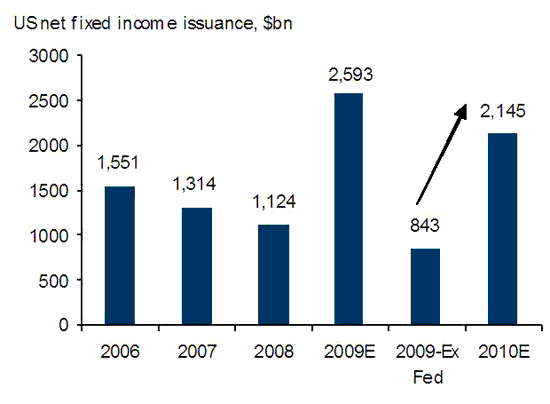

Exiting quantitative easing in 2010: Dollar positive, rates negative

A priori, one would have expected the bold US fiscal stimulus to have already shown its teeth by now; after all, the US fiscal deficit will be close to -12% of GDP in 2009. So isn’t the mild steepening of US rates (roughly 80bp for ten-year Treasuries since March) disappointing? We believe that the stimulus has barely affected the market yet, courtesy of the unrelenting efforts of the Fed to purchase long-term risk-free assets. The supply of fixed-income issuance in the US has more than doubled in 2009 relative to the average of recent years (Figure 3), but the net issuance net of the Fed’s purchases – that is, the supply of assets that effectively hits the private market – is expected to be only $845 billion in 2009, around 30% smaller than in normal times. We can safely say that the effect of the fiscal expansion on US bond markets has been dramatically offset by the Fed’s quantitative easing.

Figure 3. Net supply of riskless US assets, net of Fed purchases

Source: Barclays Capital.

But the supply net of Fed purchases is expected to rise considerably in 2010, both as quantitative easing purchases taper off and the supply of US Treasuries ramps up (an increase to $2.1trillion seems likely, almost twice as large as a normal year). Moreover, short-term US rates are also likely to increase in 2010 if expectations about the US economy continue to be revised upward. Thus, even if demand for riskless assets remains temporarily high in 2010 (due to a steep yield curve and large demand for riskless assets by capital-scarce banks), these suggest strong upward pressures for US long-term rates.

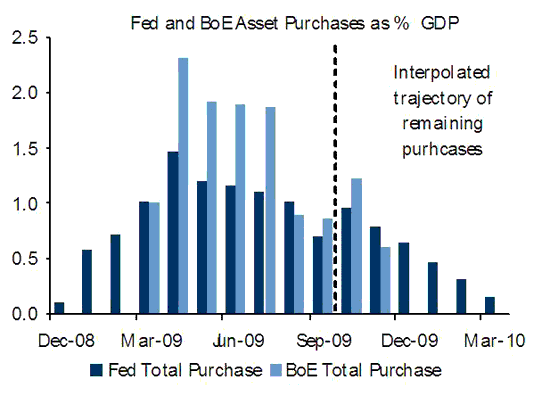

Quantitative easing purchases also have had crucial implications for currencies. As we highlighted in March, quantitative easing is a policy that favours “rates over currencies” in the sense that the central banker chooses to keep rates low at the expense of a weaker currency. In a recent report, we document how the directional implication of global quantitative easing are consistent with the departures from the so-called recovery trade observed over the summer months. In particular, they are consistent with the rally in equities without an increase in long-term yields, the fact that the effective dollar index continued its decline (consistent with the strong quantitative easing in the US relative to the rest of the world), the yen appreciated vis-à-vis the dollar (consistent with the relative tightening in Japan), and sterling weakened against the euro and yen (consistent with the relatively stronger quantitative easing in the UK).

As a result, the timing of the remaining asset purchases is critical for the evolution of rates and currencies in coming quarters. Asset purchases of around 3% of US GDP remain in the pipelines (Figure 4). The Fed has said that, without changing the total amount of its agency mortgage-backed securities and agency debt purchases, it would “gradually slow the pace of these purchases in order to promote a smooth transition in markets and anticipates that they will be executed by the end of the first quarter of 2010.” Whether the Fed’s quantitative easing will slow down enough in the coming months to imply higher rates is uncertain. It will likely continue to put downward pressures on the dollar temporarily, but the pressure for lower rates is bound to be smaller. The increase in supply and the continuation of the unwinding of risk aversion should be enough to get long-term yields rising again by the end of 2009.

Figure 4. Evolution of Bank of England and Federal Reserve asset purchases

Source: Barclays Capital.

This implies an interesting scenario for 2010 where quantitative easing in the US is set to end. The implications for long-term rates are clear – they can only move up. But contrary to the popular view of a continuously weaker dollar, the phasing out of quantitative easing implies that the dollar may strengthen in 2010 relative to other currencies, especially if the Fed swings into tightening mode faster than Europe and Japan.

The misleading undoing of global imbalances

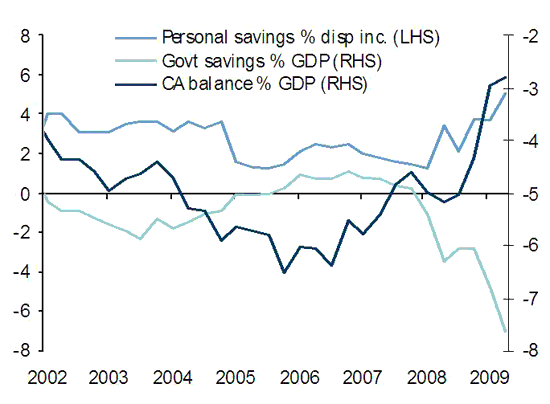

Some commentators would add the sharp improvement in the US current account deficit to the set of supportive factors to the dollar in 2010. Figure 5 shows that the US current account deficit fell from 6.5% of GDP in 2006 to about 3% of GDP in the second quarter of 2009, reducing the net supply of dollar assets to the world by more than half. But the narrowing of the US current account deficit may not be as benign for the dollar as most believe, as it partly reflects temporary considerations that mask the effects of US fiscal policy on the dollar.

Figure 5. The US current deficit and savings, 2002 – 2009

Source: Federal Reserve, Bank of England, Barclays Capital.

First, the reduction of global trade balances is partly the result of the cyclical collapse in global trade. A proportional contraction of imports and exports has the effect of moving deficits and surplus closer to equilibrium. As soon as global trade picks up, the process is likely to be at least partially reversed. Thus, the decline in the US current account deficit has temporary components that may have initially led to an overcorrection. Second, as Figure 5 shows, the improvement in the current account was the result of the sharp fall in investment, as the increase in personal savings has been more than offset by the public dis-saving (the “savings drain” discussed in our previous column). If a strong US rebound materialises, this could imply that investment finally starts increasing after a long period of contraction and, as risk aversion simultaneously fades away, a growing US current account deficit may face tougher financing terms through 2010. In terms of the value of the dollar, this is likely to have a negative impact, partly compensating the supportive role of the relative tightening of US monetary policy.

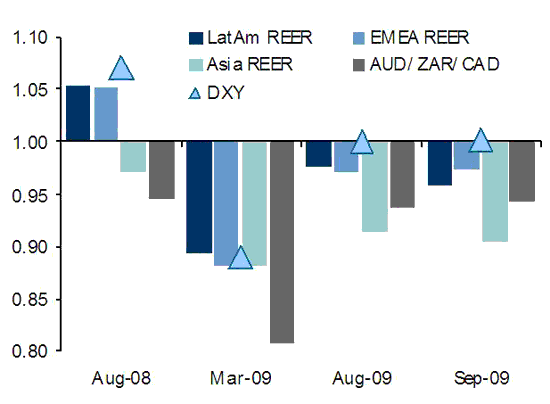

The dollar path relative to emerging market currencies may face old challenges. The post-crisis version of the so-called Bretton Woods II – the desire of some emerging markets’ central banks to prevent sharp currency fluctuations through leaning-against-the-wind intervention – is likely to imply that the countries with less central bank resistance will likely have their currencies strengthen the most relative to the dollar in the next year.¹ Thus, while currencies in emerging Asia and Latin America appear the natural candidates to appreciate vis-à-vis the dollar, the undoing of global imbalances may also fall disproportionately on more flexible G10 commodity currencies such as the Australian and New Zealand dollars (and even on the euro), a pattern that has become more visible in recent weeks (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The path of less resistance: G10 vs. emerging markets

Source: Barclays Capital.

In short, in contrast with growing dollar scepticism and even though US external accounts continue to point to dollar weakness despite the recent correction, the fast rebound of the US economy and the undoing of the monetary stimulus may deliver higher rates in lieu of a weaker dollar in 2010.

Footnotes

1 See Kiguel and Levy-Yeyati (2009). If the crisis taught anything to central bankers, it was the convenience of liquid foreign currency reserves in times of trouble. In a recent paper, Obstfeld et al. (2008) make a strong case for the prudential motive for reserve accumulation.

References

•Broda, C., P. Ghezzi and E. Levy-Yeyati (2009), “The new global balance: Financial de-globalisation, savings drain, and the US dollar”, VoxEU.org, 22 May.

•Kiguel, A. and E. Levy-Yeyati (2009), “Back to 2007: Fear of appreciation in emerging economies”, VoxEU.org, 29 August.

•Obstfeld, M., J. Shambaug, and A. Taylor (2008), “Financial Stability, the Trilemma and International Reserves”, NBER Working Paper 14217.

•IMF(2009) World Economic Outlook, Crisis and Recovery, April.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Superb article!!

“We find ourselves at the crossroads with respect to the near-term direction of the dollar. From a technical perspective, my work argues that the dollar is extremely oversold and is “ripe” for a sharp, sustainable near- and possibly medium-term recovery rally.

With the dollar so oversold, it is dry timber susceptible to the slightest spark — and another round of more forceful administration rhetoric or a few phone calls from the Federal Reserve trading desk to a few major players in the FX interbank market might trigger the necessary response.

At that juncture, the Law of Unintended Consequences surely will kick in, and who knows what will transpire thereafter? My sense is that a dollar crisis will make the subprime/credit crisis look like child’s play.”~

Mike Paulenoff, MPTrader

A rise in the dollar, will give more than just a correction in the Indices; its weakness is the only reason markets are not falling.

The recent exuberance in gold will also wane precipitously.