Will the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) current large-scale asset purchase program, so-called QE3, continue to melt away as spring arrives? The release of the minutes from the January meeting of the FOMC, along with commentary from various participants in that meeting (noted in rapid succession here, here, and here, for example) have left the distinct impression that the answer is most probably yes.

The anticipated winding down of asset purchases almost inevitably invokes a habit of language concerning what it all means for the stance of monetary policy. From the New York Times, for example, we have this (emphasis added):

When Federal Reserve officials last met at the end of January, they were surprised by the strength of the economy, cheered by the optimism of consumers and convinced they should continue to dismantle the Fed’s economic stimulus campaign, according to an account the Fed released Wednesday.

The sentiment expressed in that highlighted passage is front and center at the G-20 meetings, currently taking place in Australia (again, emphasis added):

Setting the scene for this weekend’s Group of 20 meetings, Australian Treasurer Joe Hockey’s main challenge was to avoid appearing partial in the escalating blame-game between the U.S. and developing countries over the recent exodus of capital from emerging markets….

Emerging market countries like India and Brazil have blamed the wide-scale selloff in local stocks, bonds and currencies on the Federal Reserve’s plan to exit gradually from monetary-stimulus policies, which last year began sending investors into a panic.

Here’s the thing. It is not at all clear that winding down asset purchases means an exit from or dismantling of monetary stimulus, gradual or otherwise. In Atlanta Fed President Dennis Lockhart’s words yesterday:

In our public remarks over much of last year, my colleagues and I stressed a couple of very important messages. First, even with the phase-out of asset purchases, the basic stance of policy remains highly accommodative. To translate, the Committee intends to keep interest rates very low. The second message was that the QE program and the Fed’s policy interest-rate target are two separate tools of policy. Consequently, we can wind down the asset purchases—a program that was meant to provide temporary, supplemental “oomph” to the low interest-rate policy—and preserve the accommodative positioning of policy appropriate for the reality of our economic situation.

But those are not just words. Several months back, Jim Hamilton publicized the work of Cynthia Wu and Dora Xia (former and current students of his), who have developed a method of using term structure data to infer the “shadow,” or implicit, monetary policy rate. (Follow-up posts appeared thereafter at Econbrowser—here and here—and from the crew here at macroblog.)

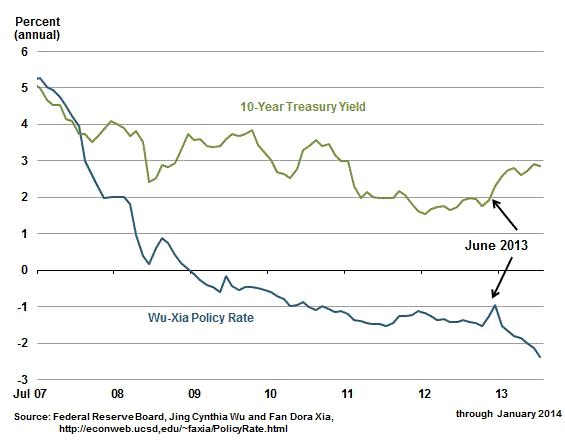

Just recently, the Wu-Xia data has been updated, giving us a first glance at the post-taper shadow policy rate (see the chart):

Both Treasury yields and the shadow policy rate did in fact spike last June following then-Chairman Ben Bernanke’s post-FOMC press conference, wherein he signaled that the asset-purchase taper was indeed on the table. But he also made the point that bringing down the QE pillar of the Fed’s policy mix is decidedly not the same thing as bringing monetary stimulus to an end, a message that was subsequently emphasized by Fed officials many times, in many forums.

Though financial market participants may have been convinced that the taper meant tightening initially, it does appear that communications and forward guidance have done the trick of more than reversing that initial impression. At the very least, the Wu-Xia calculations are consistent with that interpretation.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply