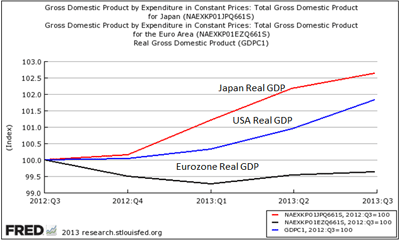

(click to enlarge)

Source: ST. Louis Fed

The always colorful Ambrose Evans-Pritchard has done it again. He has cleverly framed the varying monetary policy responses in the advanced economies as falling under either the QE block or the EMU block. As he notes, the evidence is clear as to which block has done better:

The US, UK and Japan are all recovering, moving closer to “escape velocity”. The Swiss National Bank – that bastion of orthodoxy – has kept its economy on an even keel by quietly amassing a bond portfolio equal to 85pc of GDP.

The crippled eurozone alone has chosen to stagger on defiantly without monetary crutches. The result has been a double-dip recession of nine quarters, the longest since the Second World War. The austerity regime has been self-defeating even on its own crude terms. Debt ratios have ratcheted up even faster.

[…]The diverging fortunes of the QE bloc and the EMU bloc prove beyond doubt that monetary stimulus packs a powerful punch. Without becoming entangled in the vendetta between Friedmanites and Keynesians – I value the insights both in the post-bubble phase, as well as “Austrian” insights before the bubble builds – the central bank experiment of 2008-2013 shows that blasts of money can greatly offset the pain of budget cuts, even when interest rates are zero.

This is a point I have repeatedly made on this blog. The more intense the monetary policy response, the greater has been the economic recovery. That is why over the past year the recovery in Japan has outpaced the one in the U.S. which, in turn, has outpaced the recovery in the Eurozone. This pattern can be seen in the figure above.

Ambrose-Evans goes on to describe the QE critique coming out of the EMU block:

You hear a refrain in Berlin and Brussels that the recovery of the QE bloc is somehow feckless, phony and illegitimate, that the money printers are just building up more debt, putting off their day of reckoning while Europe takes its punishment early. Nothing could be further from the truth.

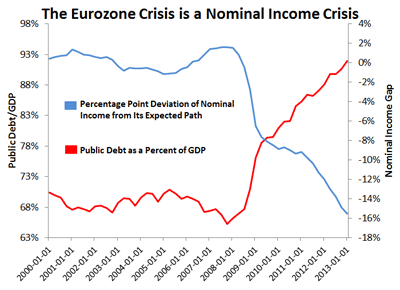

I agree, but for a different reason than Ambrose-Evans lays out in his piece. Specifically, those who see a debt crisis in Europe are only seeing a symptom of a more fundamental problem: a collapse in nominal income. This is a problem that the ECB could have prevented. The collapse in Eurozone nominal income created the debt crisis, not the other way around. The ECB allowed this collapse to emerge because its policies have been, until recently, effectively geared toward Germany. This is a point Ramesh Ponnuru and I have made before:

[Observers] tend to think of Europe’s current crisis as the result of overspending welfare states. And these states would indeed be better off with lower spending levels and less regulated labor markets. But many of the nations swept up in the euro-zone crisis, such as Spain and France, had spending and tax revenues well aligned before it hit. The true problem has again been monetary. Europe has for a decade had a monetary policy well suited to the circumstances of Germany but not to those of the rest of the euro zone and especially its periphery. Nominal income in Germany has stayed on a fairly steady trend line. In the periphery, however, it first went way up and then crashed. For the euro zone as a whole, nominal spending has fallen far below its previous trend—and has been continuing to fall farther away from it. Monetary policy therefore remains very tight in the euro zone overall. One effect of that drop-off, in Europe and in the U.S., has been to make debt burdens more onerous.

The figure below illustrates this point. It shows that below-trend growth in Eurozone nominal income–as measured by how far NGDP is from its pre-crisis trend path–has been matched by a similar rise in Eurozone government debt. The Eurozone crisis, then, is a nominal GDP crisis, not a debt crisis.

(click to enlarge)

The QE programs have been far from perfect, but they seem to have made a difference. Consequently, my bet is that history will be kind to policy makers in QE Block and frown upon those in the EMU Block.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply