I was curious to take a look at the growing student debt load and the government’s exposure to potential repayment issues.

A recent analysis of individual credit data by Donghoon Lee of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that student loans are the one category of household debt that continued to rise during the Great Recession. As of the end of 2012, student loans came to nearly a trillion dollars, more than total credit card debt, auto loans, or home equity lines of credit.

Source: Lee (2013).

Lee found that 17% of the student loans are currently delinquent. An additional 44% are not yet in repayment, because the borrowers were still in school, or had graduated but were granted deferrals or forbearances delaying their regular payments.

Source: Lee (2013).

The explosion in student debt has primarily been driven by federal funding. Historically this took two forms. The first was the Federal Family Education Loan Program, which provided federal guarantees of loans made to students by nonfederal entities. The GAO estimated that FFEL loans outstanding as of the end of fiscal year 2009 stood at $493 B. This program was discontinued as part of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. No new guarantees were issued after that date, though the Department of Education remained liable for guarantees previously issued.

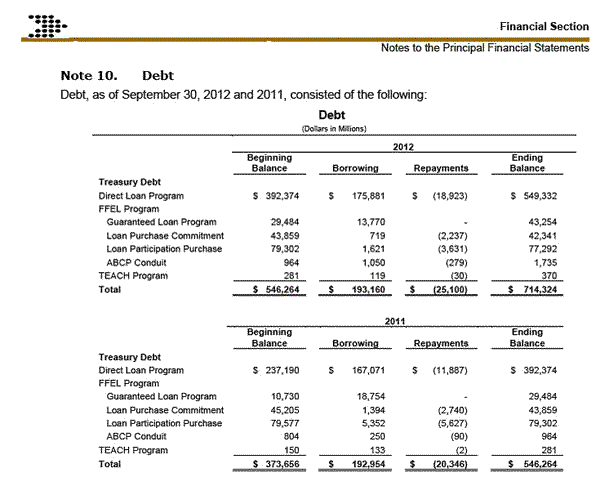

The Act replaced FFEL with greater reliance on the second form of assistance, namely direct loans from the federal government. The financing for these works as follows. The Department of Education borrows funds directly from Treasury. In effect, some of the debt auctioned by the Treasury to the public is earmarked for the student loan program. This sum is reported in Table FD-7 of the Treasury Bulletin as “Treasury holdings of securities issued by government corporations and other agencies.” This balance grew from $104 B in 2007 to $714 B in 2012. This number is included in the $11.3 T total federal debt reported by the Treasury to have been held by the public as of the end of fiscal year 2012. Although these borrowings are included in the official debt figures, they are not included in the official deficit numbers. The growth in borrowing by the Department of Education in order to fund student loans has been one reason that outstanding federal debt has increased by more than the reported deficit in recent years.

Debt owed by the Department of Education to the Treasury by category, in billions of dollars as of end of fiscal year. Blue: direct loan program; yellow: loan purchase commitment, loan participation purchase, ABCP conduit, and TEACH program; brick: guaranteed loan program. Data source: Federal Student Aid Annual Reports.

However, borrowing for the Department of Education’s direct loan program only accounts for $549 B of the $714 B balance (represented by the blue region in the graph above). Another $122 B (in yellow) comes from measures implemented in response to credit market disruptions in 2008 and 2009. These appear primarily to have been purchases of securities based on previously guaranteed student loans. Although the Department of Education is no longer extending additional credit under these programs, there evidently has not been much repayment on these loans, because the balance due Treasury from this category has receded very little in the last two years.

Particularly interesting is the brick region in the graph above, which the Department of Education describes as Treasury debt associated with the guaranteed loan program. The curious thing is that, although the program was discontinued in July 2010, the Department of Education borrowed an additional $19 B from the Treasury for this program during fiscal year 2011 (which ran from October 2010 through September 2011) and another $14 B during fiscal year 2012, for a net accumulated debt to Treasury from this category of $43 B as of the end of fiscal year 2012.

I did not find an explanation of this in the FSA annual reports— if anyone can call my attention to one I’d be most grateful. Here’s how I interpret it. Separate notes in the 2012 annual report describe “defaulted guarantee loan programs” as one of the assets held by the Department of Education. I’m inferring that the accounting convention is that when the Department needs to honor a guarantee commitment for a loan that has gone bad, since there is no separate budget appropriation for this, they borrow the necessary funds from the Treasury, and simultaneously claim a defaulted guarantee loan (on which they hope someday to collect) as the balancing asset. Here is a screen shot from the FSA annual report from which I am getting these numbers.

(click to enlarge)

Source: Federal Student Aid 2012 Annual Report, U.S. Department of Education.

If I have the correct interpretation, then most of the $43 B in that brick region and perhaps much of the $122 B yellow region represents money lost to the taxpayers so far as a result of the earlier guarantee program for which we’re not yet acknowledging that there’s been any cost to the budget.

American Action Forum suggests there may be related accounting issues with borrowing from the Treasury for the direct loan obligations as well, with significant losses for the blue region above also currently being concealed.

Econbrowser readers know that I am strongly opposed to having regular congressional votes on an overall debt ceiling for the U.S. Treasury. But establishing a separate ceiling on how much the Department of Education can borrow from the Treasury strikes me as a good idea.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply