Why have Canadian banks fared better during the crisis than their OECD peers? This column attributes their stability to their reliance on depository funding rather than more risky wholesale funding. It recommends a Pigouvian tax penalizing banks using excessive short-term wholesale funding.

During a visit to the London School of Economics last November, HM Queen Elizabeth asked a group of leading economists there: did no one see the banking crisis coming? Spotting potential bank failures is a difficult, if not impossible, task. A Lex column at the Financial Times painted a dismal picture:

“Capital adequacy ratios, for example, gave no clue as to which banks would go under. Even purer measures that compared common equity to assets were of little help. Indeed, capital ratios for those banks requiring intervention were actually higher than the group average. Examining liquidity ratios or non-performing loans versus total loans would also have been no help.”

With the benefit of hindsight, we notice that, among developed countries, Canadian banks performed relatively well during the financial turmoil. What could explain their relative resilience? Our recent IMF working paper (Ratnovski and Huang 2009) explores many factors behind the unusual resilience of Canadian banks.

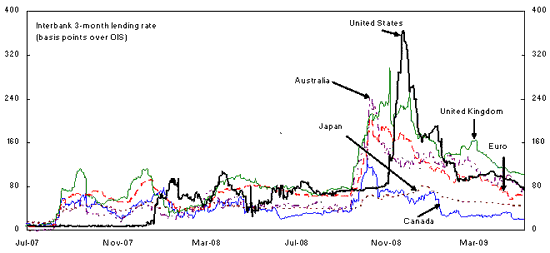

Figure 1. Spread between interbank 3-month lending rate and overnight index swap rate

Our paper analyzes the pre-crisis balance sheet structures of the largest commercial banks in OECD countries and relates them to bank performance during the turmoil. Our regression analysis shows that incidents of bank distress can be explained rather well based on just three pre-crisis accounting-based financial ratios: a critically low (below 4%) equity-to-asset ratio, insufficient balance sheet liquidity, and a funding structure that relied less on a stable deposit base and more on wholesale funding.

Empirically, the funding structure, as measured by the depository funding to total asset ratio, is the most robust predictor of bank performance during the turmoil.

How were Canadian banks different from their peers?

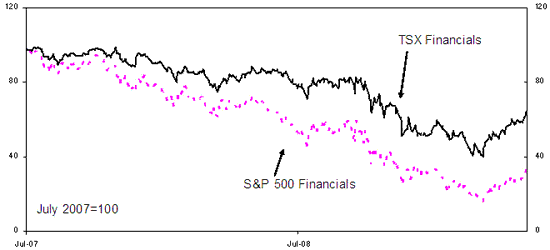

Canadian banks’ pre-crisis balance sheet structures were broadly similar to those of banks in other OECD countries with one notable exception – funding structure. Canadian banks were in the top quartile of the OECD sample in terms of their use of depository funding. The advantage of stable deposit funding may have insulated them from the freeze of wholesale funding markets, contributing to their resilience.

Figure 2. The S&P 500 vs. the Toronto Stock Exchange

Why do Canadian banks have a firmer grip on depository funding? Environments and circumstances are important factors. On the supply side, large Canadian banks, benefiting from their nationwide footprints and a universal banking model, are able to offer one-stop service to households, which helps attract and retain household savings. On the demand side, in recent years, Canadian banks experienced slower asset growth than their neighbors in the US, leading to a narrower funding gap and hence a lower need for wholesale funding in addition to household savings.

What can policymakers do about banks’ excessive use of short-term wholesale funding?

To address banks perverse risk-taking incentives, many leading policy proposals focus on introducing more cycle-proof capital regulations (for example see Raghuram Rajan’s column at the Economist). We believe that a Pigouvian tax targeting at banks’ debt structure could help as well.

In a separate paper (Ratnovski and Huang 2008), we develop a theoretical model to analyze the negative effect of short-term wholesale funding. In our model, short-term wholesale funds create liquidity risk and may lead to costly and unwarranted bank runs, but banks love them because they are relatively cheap and banks don’t internalize all the costs of liquidity risks. Short-term wholesale funds accept lower interest rates because they bear little risks. As they are able to exit earlier than others, they can shift most risks to long-term investors, retail depositors, and, eventually, the taxpayers.

The theoretic model allows us to derive a policy intervention solution, in the form of a Pigouvian tax, to correct for the perverse incentive banks have to use short-term funding. The tax formula prescribes a higher tax rate for banks using shorter maturity funding, particularly secured funding, because both features effectively give wholesale financiers higher seniority, distorting their incentives. The formula requires assessing the tax based on a bank’s total liabilities and not just insured deposits. It also prescribes a higher tax rate for banks investing more in arm’s length assets relative to small business loans.

This tax, by increasing banks’ private cost of using short-term wholesale funding, would force banks to internalize the damages on other stakeholders, and reduces banks’ incentives to rely on short-term funding. We are not alone in proposing a Pigouvian tax to address this problem. In CEPR Policy Insight No.31 (also see a companion VoxEU column), Enrico Perotti and Javier Suarez proposed a similar “liquidity charge” proportional to the maturity mismatch between assets and liabilities to equalize funding costs between short-term and long-term funding. The Perotti-Suarez proposal is well-supported by our theoretic model and has great operational feasibility under the roof of the future European Systemic Risk Council.

What have the authorities done?

Some of the FDIC’s new rules are consistent with our model’s prescription. For example, the FDIC recently assessed a special charge based on a bank’s total assets and not its total deposits, taking into account the extra risks large banks take by borrowing from the wholesale market. Assessments also increased for institutions that rely heavily on brokered deposits to fund rapid asset growth or rely significantly on secured liabilities. Assessments would decrease for institutions that hold long-term unsecured debt. The FDIC argues that the primary purpose of the secured liability adjustment is to remedy an inequity – an institution with secured liabilities in place of another’s deposits pays a smaller deposit insurance assessment, even if both pose the same risk of failure and would cause the same losses to the FDIC in the event of failure.

Disclaimer: This column presents the views of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the IMF or its Board.

References

•Financial Times (2009), “Systemic stresses”, 26 April.

•Perotti, Enrico and Javier Suarez (2009), “Liquidity insurance for systemic crises”, CEPR Policy Insight No 31.

•Rajan, Raghuram (2009), “Cycle-proof regulation” Economist 8 April.

•Ratnovski, Lev, and Rocco Huang (2008), “The Dark Side of Bank Wholesale Funding”, Wharton Financial Institutions Center Working Paper #08-40.

•Ratnovski, Lev, and Rocco Huang (2009), “Why Are Canadian Banks More Resilient?”, IMF Working Paper 09/152.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply