On Monday the IEA released its World Energy Outlook 2012. This includes an optimistic assessment of the situation in the United States:

The United States is projected to become the largest global oil producer before 2020, exceeding Saudi Arabia until the mid-2020s. At the same time, new fuel-efficiency measures in transport begin to curb US oil demand. The result is a continued fall in US oil imports, to the extent that North America becomes a net oil exporter around 2030.

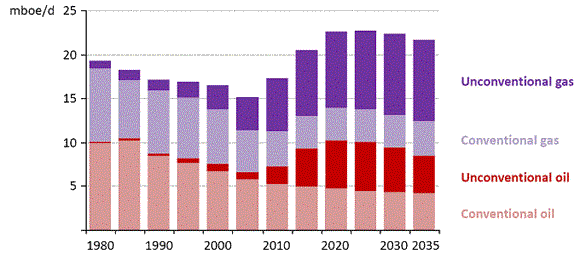

Historical and projected U.S. oil and gas production. Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2012

Stuart Staniford makes an interesting observation on the above reported numbers. The graph suggests that the U.S. will be producing a little over 10 mb/d in 2020. If that’s enough to overtake Saudi Arabia, it means that Saudi production is never going to get anywhere near the 15.4 mb/d that the kingdom had been predicted to reach in 2020 according to the IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2005 released seven years ago.

The pink or red regions in the above graph appear to be reporting the sum of field production, lease condensate, and natural gas liquids. The latter by 2011 had come to account for 28% of the total, and you can’t drive your car on ngl. It’s also interesting to note that according to the graph, U.S. production is expected in 2020 to get back to the level previously seen in 1985– or about 800,000 b/d below the all-time U.S. peak in 1970– before beginning to decline again after 2020. And all of the gain between now and 2020 comes from unconventional production, presumably largely oil and ngl from tight formations. Again quoting Stuart:

I am less persuaded myself that using a thousand oil rigs to generate an extra one million barrels per day of oil is necessarily a sign of a large and long-term sustainable increase in US oil production (as opposed to, say, frenzied scraping of the bottom of the barrel). But, still, I’m not certain beyond a reasonable doubt just how deep this particular barrel can be scraped.

Another interesting number to compare to this 10 mb/d production anticipated for the U.S. in 2020 is the 18.9 mb/d of crude oil and petroleum products currently being consumed by the United States. If the U.S. is indeed to approach energy independence, it mostly must be due to a significant drop in U.S. demand for oil, perhaps resulting in part from increased use of natural gas for transportation. And conservation of this impressive magnitude is hardly the outcome one would associate with a scenario of falling oil prices over the next decade.

Finally, another item from the WEO summary bears noting: Iraq accounts for 45% of the growth in total world production that IEA is forecasting between now and 2035. I commented on the potential for future production from Iraq earlier. Here I will only repeat that one assumption of any such forecast is that Iraq is going to be a substantially more stable place over the next decade than it has been over the last three.

None of this is to deny that U.S. production of oil and gas from tight formations is going to bring significant economic benefits to the United States, nor that the geologic potential for a remarkable transformation in Iraq could well be there. But I think anyone who concludes from this report that we are about to return to the kind of world we inhabited in 1970 may be in for an unpleasant surprise.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply