Despite the EZ doom and gloom discussion, the US and EZ are at roughly the same point in their recovery from the global crisis. This column argues that the ‘austerity kills’ narrative of Krugman and Layard misses the basic point. Public debt ratios without retrenchment would become unsustainable. The fact that austerity is costly does not mean it should not be undertaken.

Austerity is killing growth in Europe! This narrative is now firmly established among many influential economists and policymakers (Layard 2012). The data do not support this view – at least if one takes a medium-term view.

Since the end of the bubble in 2007, the economic performance of the US has been very similar to that of the Eurozone, although the US has used a much larger dose of fiscal expansion.

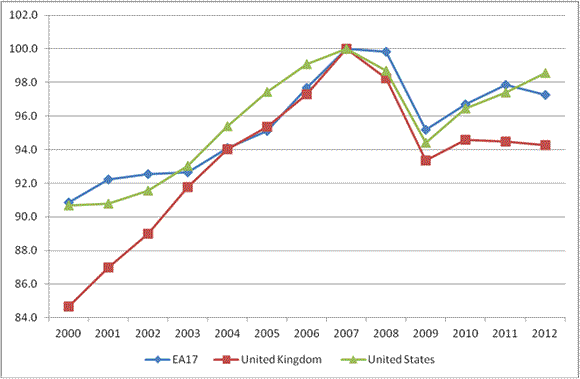

As shown in the figure below, the US and the Eurozone have actually followed a very similar pattern:

- In terms of GDP per capita, the US and EZ are both about 2% below their 2007 mark;

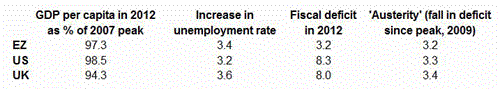

- In terms of unemployment, we saw a rise of about 3% everywhere (see the table below).

Figure 1. Transatlantic comparison in GDP per capita

Source: Own calculations based on Commission data

However, fiscal policy has been very different.

- In the US and the UK, the general government deficit is still around 8%, compared to a little over 3% of GDP in the Eurozone.

Austerity is about the reduction in deficit spending, not its level. On this account one is tempted to ask: what austerity? The last column in the table shows that all three economies have reduced deficits by 3% of GDP since the peak of 2009, i.e. on average about 1% of GDP per year. The portrayal of a savage austerity drive, hitting Europe especially, is thus plainly wrong.

Table 1. Unemployment in the Eurozone, the US and the UK

Source: Ameco

The case of the UK is instructive. The economy with the strongest dose of expansionary policy (both monetary and fiscal) is also the one where growth (measured by GDP per capita) has been the weakest. Of course, one could argue that the UK was particularly exposed to the bust because financial services make up a large part of its GDP, and the loosening may be a reaction to the weaknesses. However, it remains true that its economy, which is supposed to be the most flexible in Europe, has not recovered from the shock five years later, despite massive doses of expansionary fiscal and monetary policy coupled with a devaluation.

Given the massive negative shock coming from the tensions in the sovereign debt markets, it is likely that the relative performance of the Eurozone will deteriorate from now on. However, this should have little bearing on whether austerity has so far had a decisive impact on growth in Europe.

Nevada and California: The US’s Ireland and Spain

Particular countries in Europe have seen austerity-induced depressions. But the US also has pockets of very depressed areas. For Ireland and Spain, read Nevada and California (and for Greece, read Puerto Rico). The proper comparison is thus between two continental-sized economies, both of which harbour considerable diversity.

Krugman and Layard

Krugman and Layard (2012) plead: “Stop this austerity now”. But “this austerity” consists of a rather gradual reduction in deficits, which, at its present pace, would get the US and the UK only by 2017 back to the point where they started in 2007.

It is certainly true that the evidence shows that austerity is not expansionary. And Krugman and Layard are also correct in pointing out that when private demand started to collapse in 2008, public demand had to be stepped up to prevent the Great Recession from becoming a second Depression. Four years later, however, some retrenchment of the public sector is unavoidable.

Public debt ratios without retrenchment would become unsustainable, even if “this austerity” implies a temporary loss of employment and output. The fact that austerity has costs does not imply that it should never be undertaken. Rather, the results from the ‘Great Response’ to the Great Recession, which involved first considerable fiscal expansion and then gradual retrenchment, suggest that the benefits from deficit spending were smaller than expected, and possibly smaller than the cost of the austerity needed to bring deficits back under control.

References

•Krugman, Paul and Richard Layard (2012), A Manifesto for Economic Sense.

•Layard, Richard (2012), “The tragic error of excessive austerity“, VoxEU.org, 6 July.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply