MBIA (NYSE:MBI) is down $1, which is about 20% on a downgrade by JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM). This after surging to almost $7 in recent days on reports that the company might be able to foist some of their MBS exposure back to the originating banks.

The interesting question to me (since I wouldn’t actually touch MBIA’s stock with a 10-foot Gaffi Stick) is whether there is any possible business left for MBIA even if the optimistic view of their legal battles comes to fruition. As we all know, MBIA is attempting to separate their muni and structured finance businesses in an attempt to someday write new muni insurance contracts. But is that still a viable business?

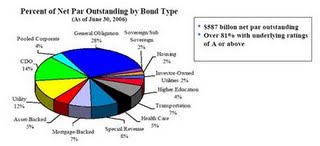

Before we answer that, we need to look back at what muni insurance was all about. There is a myth out there that muni insurance was used primarily by weaker credits as a means of lowering their interest expense. That’s not really true. I did some digging through old MBIA investor presentations (funny to hear them boast about “penetration” into the structured finance business) and found this chart from 2006:

There’s nothing magic about 2006, I just wanted a period which was clearly before structured finance risk started becoming a problem to show what muni underwriting was like during the “good times.” We see 28% of the total par outstanding was in GO munis. I did some rough calculations and it comes out to something like 44% of muni underwriting was in GO’s. Notice also what you see very little of: healthcare, housing, industrial development (zero). In other words, the riskier segments of the muni market are clearly under-represented.

The point is to say that muni insurance was not typically used as a true credit enhancement, at least not in terms of avoiding default. By now you’ve heard the stellar record of GO bonds, which almost never default. So who needs the insurance?

I argue that the need for muni insurance is borne more out of information asymmetry than actual credit enhancement. By this I mean, investors in municipal bonds often struggle to get complete and up-to-date information about a given municipality. Take for example a random school district in Pennsylvania: Glendale School District. Go to their website and try to find their financials. I couldn’t find them. So if you had bonds for the Glendale School District, how would you follow their financial performance? You could potentially get someone from the Superintendent’s office to send you reports, but odds are they would only be produced annually and with a long delay before the report is available.

Imagine if a corporation wanted to sell bonds, but refused to report regular reports. Would the bond be sellable?

Muni insurance filled this gap. The insurer could demand certain information and/or legal language in the bond deal that investors could not. Especially not individual investors. In that way, muni insurance was a little like title insurance on a home. No one expects to use it, it very rarely comes into play, but in the event that something truly crazy happens, like the Orange County scandal, investors are covered. The insurer deals with it.

So I’d say that municipal bond insurance served a certain public purpose. Allowing local municipalities to sell bonds at attractive rates.

And yet, I still think muni insurance is a dying business. Why? Because in a way, MBIA/FGIC/XLCA/Ambac’s problems are very similar to Fannie Mae (NYSE:FNM) and Freddie Mac’s (NYSE:FRE). The for-profit nature of the firm got in the way of realizing the public purpose. Now obviously MBIA was never a “public” entity in the way Fannie/Freddie were, but I think the point stands. Investors aren’t going to trust insurance the way they used to ever again.

Still, the need for resolving this information availability problem remains. I ultimately think the better solution is for states to form their own credit enhancement programs. This could be accomplished through a bond bank, which is common in Indiana and California. It would have to be altered from some of the existing bond bank programs, where the underlying credit was only whatever municipalities participated in the specific issue. In the old days, a California Communities bond issue might only be backed by 2 or 3 local California towns, but would also carry Ambac (NYSE:ABK) insurance. That used to be fine, but now its obviously not going to work. California could alter their bond bank program such that a surplus account is created to make up any losses on individual loans, which would allow for a better overall rating on their program.

Another possibility is some sort of state intercept program. This would be where the state agrees to backstop local municipal school district deals. There are such programs in force in Texas, for example. The problem here is that such programs are usually only available for school district bonds, not for other local government needs. So if Pflugerville School District needs a new roof on the high school, that can be done through the Texas Public School Fund. But if the town of Pflugerville needs a new roof on City Hall, there is no state help.

I would like to see these kinds of programs expanded without the help of the Federal government. One of the problems that always worries me about municipal finance, and its lack of transparency, is that good fiscal management can’t always been differentiated from budgetary shell games, especially on the local level. Again, this is an area where the muni insurers were a benefit since they could enforce certain standards better than individual investors could. I could see a state-level insurance pool filling this role, making sure local issuers keep to some standard of good fiscal management. But if it rises all the way up to the Federal level, there will be too much distance between the issuer and the guarantor. Actually used to rely heavily on insurance.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply