I am working on a fairly long entry that I will post this weekend about why a trade rebalancing and a consumption/savings rebalancing will take place in both China and the US whether or not we want it. This week has been crazy, among other reasons because a festival in Taiwan has invited one of our indie bands and one of our experimental bands (Carsick Cars and White) to perform this weekend at the Music Terminals Festival in Tao Yuan City. Getting visas for these kids has been brutally difficult and they actually had to cancel one of their club gigs, on Thursday, because of problems with getting things done on time. Still, if any of my readers are going to be in Taiwan this weekend, I strongly recommend that you check out the festival, which besides the two Beijing representatives features a lot of great bands from around the world (or if you prefer club gigs, check them out Friday night at a pre-festival show at The Underworld, in Taipei).

So much for the good news. The bad news is described in an alarming article in today’s Wall Street Journal which shows that trade tensions are continuing to rise.

European Union trade officials approved pre-emptive penalties on imports of steel pipe from China, a precedent-setting move that suggests the trading bloc is growing more protectionist in the face of the economic downturn.

Tuesday’s vote by trade officials from the EU’s 27 member states is significant, say trade experts, because they accepted an argument from steel producers – including the world’s largest by volume, ArcelorMittal – that punitive tariffs are needed to protect them from the threat of underpriced imports from China. Previously, complainants have had to prove the imports had already hurt their businesses. Trade lawyers say they expect a host of industries to ask the EU for protective tariffs in August.

I have been hearing rumblings for a while about tougher stances being taken in Europe and the US in response to the perception that China is exacerbating the global contraction in demand by increasing subsidized resources available to manufacturers, most importantly by channeling a huge increase in lending at interest rates subsidized by Chinese household consumers and socializing the risk. These new protectionist moves seems to be an expression of just this. The article goes on to say:

Basing a claim on the threat of injury “is a perfectly legal strategy, but it has simply not, until now, been used as a matter of EU policy,” says Nikolay Mizulin, a Brussels-based trade lawyer with Hogan & Hartson LLP. This case “is a sign of growing protectionism and could open the floodgates to many more industries who believe they deserve protection.”

Mr. Mizulin and other trade lawyers say they expect many industries to seek protective tariffs next month.

As I have been arguing for over a year, as unemployment around the world rises and as the necessary contraction in US net demand picks up pace, there was inevitably going to be a conflict with China as Chinese policymakers responded to the collapse in trade in the only way they could, by substantially stepping up investment. The result is that China’s trade surplus has contracted very slowly – much more slowly than the contraction in the US trade deficit – and the result was a huge squeeze on the tradable goods sectors around the world.

The fact that policymakers in Europe, China, Japan and the US seem to have no clue as to how difficult the transition for each of the other countries is likely to be, and so are doing not nearly enough to coordinate their response (in fact lecturing and finger waggling seem to the favorite forms of policy coordination), makes trade conflict almost a dead certainty. I don’t think there are necessarily any bad guys here – each country is desperately doing what it can to get itself out of this mess – but there is a lot of failed opportunity and I am pretty sure that the trade environment will continue to decline.

The problem is illustrated in two interesting recent pieces. My friend Dan Rosen, of the Rhodium Group, has a very illuminating July 17 report that shows the composition of Chinese growth in the past decade. He shows that for the past five years net exports accounted for about 10% to 15% of Chinese GDP growth, before collapsing n to minus 41% in 2009 YTD.

Until recently investment’s share of GDP growth peaked at around 65% in 2003 – a very high share by any standard – and going back the full thirty years of China’s reform period achieved an historical high astonishing of 81% in 1985. From 2005 to 2008 the investment share of GDP growth averaged around 40% – still high – and then in the first half of this year accounted for a mind-boggling 88% of this years GDP growth.

This year’s growth, in other words, is almost wholly a function of the massive increase in investment, and this increase in investment started out largely in the form of reopening production facilities and producing more “stuff”, without any significant rise in consumption. As we know, when production increases faster than consumption, either the trade surplus or inventories must rise.

On that note Xinhua published the following article on Monday:

The per capita consumption spending volume of Chinese urban residents stood at 5,979 yuan (875 U.S. dollars) in the first half of this year, up 8.9 percent year on year, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced Monday. Deducting price factors, the growth reached 10.3 percent.

The per capita disposable income of Chinese city dwellers rose 9.8 percent year on year to 8,856 yuan in the first six months. Deducting price factors, the increase reached 11.2 percent, said the NBS.

Consumption has been rising at around 9% a year for the past several years. Notice that if GDP growth slows to under 9%, the savings rate in China will decline.

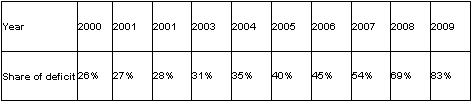

The second interesting piece is put out by the Economic Policy Institute, a group I believe not noted for its commitment to free trade. It shows China’s share of the US trade deficit excluding oil. According to their numbers:

Perhaps as a consequence of a fiscal stimulus aimed at boosting investment and production, China’s share of the US trade deficit has grown significantly. Since the US trade deficit is shrinking quickly, this means that other exporters are getting killed. As I have argued for a while, this is not sustainable and will almost certainly cause trade tensions to erupt.

Does this mean China is behaving in a predatory way? I don’t thinks so. I have warned for a long time that it would be very difficult for China to make the necessary transition to a consumption-led economy quickly enough to accommodate the global adjustment taking place. Unless it is willing to see its economy collapse, there is simply no way China can reduce its negative net demand quickly enough to match the contraction in US demand and so avoid squeezing and so avoid squeezing the hell out of the global tradable goods sectors. That is why policy coordination is so important, especially between China and the USD, and of course that is why I continue to be a pessimist. I do not think this policy coordination is taking place. I will write about this more later this week.

To continue the discussion of last week, we are getting more conflicting signals about policy confidence. On the one hand Bank of China seems to love this party. According to an article in today’s Bloomberg:

Bank of China Ltd., which doled out the most loans among Chinese banks in the first half, plans to keep expanding credit unless the government clamps down on the nation’s record lending boom.

The nation’s third-largest bank will maintain its original target of generating about 10 percent of China’s new loans in 2009, Beijing-based spokesman Wang Zhaowen said by telephone yesterday. Bank of China may “fine tune” its strategy in line with any government policy changes, he said.

…Bank of China will continue to lend to 10 key industries with government policy support, including steel, shipbuilding and automobile, Wang said. About 30 percent of its loans went to those industries in the first half.

On the other hand two of the other members of the Big Four seem a lot more cautious. Today’s South China Morning Post has this article:

Mainland’s two biggest state-owned commercial banks have put a lid on their lending targets for the year, according to domestic media reports, in a move that will significantly slow overall credit growth in the second half. Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) is aiming to issue full-year new loans of 1 trillion yuan (HK$1.3 trillion), while China Construction Bank (CCB) has set a goal of 900 billion yuan, Caijing magazine reported.

The two banks, mainland’s largest by market value, granted new loans of 825.5 billion yuan and 709 billion yuan, respectively, in the first half. If they stick to their reported targets, this would imply that ICBC would have already issued 83 per cent of its full-year lending total, while CCB would have already issued 79 per cent.

It is surprising to me that these members of the Big Four are responding so differently, at least in public. I wonder if the management of the different banks belong to different factions and so interpret the fiscal stimulus package differently. Perhaps my friend Victor Shih, who understand these things better than I do and who sometimes reads my blog might comment?

Finally the Financial Times on Monday continued the thread discussed in my Saturday post with an article called “China warns banks over asset bubbles.”

Chinese regulators on Monday ordered banks to ensure unprecedented volumes of new loans are channelled into the real economy and not diverted into equity or real estate markets where officials say fresh asset bubbles are forming. The new policy requires banks to monitor how their loans are spent and comes amid warnings that banks ignored basic lending standards in the first half of this year as they rushed to extend Rmb7,370bn in new loans, more than twice the amount lent in the same period a year earlier.

…Beijing’s concerns are echoed in other countries across the region, most notably South Korea, where the government says it is taking steps to cool a real estate bubble, and Vietnam, where the government has ordered state banks to cap new lending to head off inflation. regulators are now concerned that too much money is being lent by the state-controlled banks and the country’s tentative economic rebound could come at the cost of a stable financial system.

In statements published last week, Wu Xiaoling, who recently retired as deputy governor of the central bank, warned new lending this year would probably reach as high as Rmb12,000bn, a staggering increase of 40 per cent of the entire stock of outstanding loans in just one year.

…Ms Wu hinted Beijing may soon raise the amount of money banks must hold on deposit with the central bank, marking a change of policy from last year when it aggressively slashed the reserve requirement ratio and interest rates.

The central bank has also ordered 10 banks, including Bank of China, to buy Rmb100bn worth of central bank notes with a maturity of one year and a return of just 1.5 per cent, according to Chinese media reports. This move is interpreted as a warning to banks that have been the most active lenders that they should now start to rein in their excessive behaviour.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply