We can sit and wring our hands, or we can get to work.

Nobel laureate and Columbia University economics professor Joseph Stiglitz sees a long-term problem in the current U.S. economics malaise:

It has now been almost five years since the bursting of the housing bubble, and four years since the onset of the recession. There are 6.6 million fewer jobs in the United States than there were four years ago. Some 23 million Americans who would like to work full-time cannot get a job. Almost half of those who are unemployed have been unemployed long-term. Wages are falling– the real income of a typical American household is now below the level it was in 1997….

Even when we fully repair the banking system, we’ll still be in deep trouble– because we were already in deep trouble….[I]n the years leading up to the recession, according to research done by my Columbia University colleague Bruce Greenwald, the bottom 80 percent of the American population had been spending around 110 percent of its income. What made this level of indebtedness possible was the housing bubble….

The trauma we’re experiencing right now resembles the trauma we experienced 80 years ago, during the Great Depression, and it has been brought on by an analogous set of circumstances. Then, as now, we faced a breakdown of the banking system. But then, as now, the breakdown of the banking system was in part a consequence of deeper problems….

Today we are moving from manufacturing to a service economy. The decline in manufacturing jobs has been dramatic– from about a third of the workforce 60 years ago to less than a tenth of it today. The pace has quickened markedly during the past decade. There are two reasons for the decline. One is greater productivity– the same dynamic that revolutionized agriculture [in the Great Depression] and forced a majority of American farmers to look for work elsewhere. The other is globalization, which has sent millions of jobs overseas, to low-wage countries or those that have been investing more in infrastructure or technology.

Stiglitz’ Columbia colleague Jeffrey Sachs had a similar assessment:

The collapse of housing is actually a symptom rather than the fundamental source of US economic weakness.

The structural problem is that America has lost its international competitiveness in basic industries including textiles, apparel, and several other areas of manufacturing. The production jobs are now in China, India, and elsewhere, where wages are much lower while productivity is more or less comparable to the US (and where production often involves US companies, using US technologies, producing overseas and re-exporting to the US market). Only US college grads can resist the international competitive pressures; high-school grads have found the labor market fall out from beneath their feet.

I agree with Stiglitz and Sachs that America’s long-term problems played an important role in putting us we are today. However, I take a different view from either of them on what we should try to do about it. My suggestion is that America should try to return to what some scholars maintain was the original source of America’s success, which came from using North America’s abundant natural resources as a basis for a competitive advantage in manufacturing.

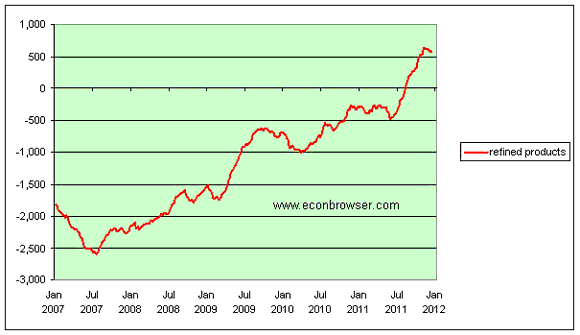

I recently highlighted one way that process made an important contribution in 2011. In 2008, the U.S. imported 1.8 million more barrels every day of refined petroleum products than we exported. Increased production of North American crude oil together with declining U.S. consumption have given Midwest refiners a huge competitive advantage internationally since then. As a consequence, the U.S. moved from being a net importer of refined products to exporting 0.4 more million barrels a day than we imported in the second half of this year.

U.S. net exports of refined petroleum products, average of most recent 12 weeks, in thousands of barrels per day, Jan 5, 2007 to Dec 16, 2011. Data source: EIA.

Monday’s Wall Street Journal has some other examples:

The boom in low-cost natural gas obtained from shale is driving investment in plants that use gas for fuel or as a raw material, setting off a race by states to attract such factories and the jobs they create.

Shale-gas production is spurring construction of plants that make chemicals, plastics, fertilizer, steel and other products. A report issued earlier this month by PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC estimated that such investments could create a million U.S. manufacturing jobs over the next 15 years.

West Virginia is vying with Pennsylvania and Ohio to attract an ethylene plant that Royal Dutch Shell PLC said it plans to build in the Appalachian region to take advantage of the plentiful new gas supplies….

“This shale gas development is a game-changer of huge proportions,” said Dan DiMicco, chief executive officer of Nucor Corp., a steelmaker based in Charlotte, N.C. Nucor is building a $750 million plant to make iron from natural gas and iron-ore pellets near the Mississippi River in St. James Parish, La. Mr. DiMicco said the investment wouldn’t have been possible without the lower costs that have come with shale gas.

And here’s a third example from Inland California’s Daily Bulletin:

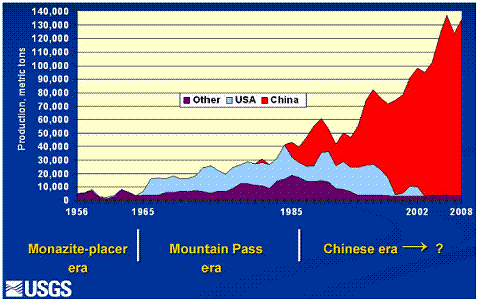

Molycorp announced it received permission from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to conduct exploratory drilling operations near its Mountain Pass [rare-earth-element] mine….

Before December 2010, the Mountain Pass mine had been shut down for eight years due to environmental reasons.

In the months since, Molycorp has not only reached profitability, but it has also acquired processing facilities in Arizona and Estonia, while also building expanded milling and ore separation facilities at its Mountain Pass mining site.

Molycorp also announced a joint venture with two Japanese companies, Mitsubishi and Daido Steel, in which the three companies would work together to produce high-tech magnets.

These “rare earth elements” are vital in all kinds of high-technology manufacturing, and are another area where the U.S. used to play a leading role. We could do the same again.

Global rare-earth oxide production. Source: Tse (2011).

I recommend that, rather than wring our hands in despair, America should respond to our long-term challenges by making note of the natural advantages we already enjoy and figuring out how to make the best use of them.

Getting the U.S. economy growing

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply