The debate over the shape of the recovery continues unabated. Equities, at least this week, are voting in favor of the V-shaped recovery, with the Dow pushing past the 9,000 mark for the first time since January. Never one to accept good news at face value, Nouriel Roubini predictably took the opposite position:

A “perfect storm” of fiscal deficits, rising bond yields, “soaring” oil prices, weak profits and a stagnant labor market could “blow the recovering world economy back into a double-dip recession,” he wrote in a research note today. “It is getting more likely unless a clear exit strategy from the massive monetary and fiscal stimulus is outlined even before it is implemented.”

Roubini, chairman of Roubini Global Economics and a professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, predicted that the global economy will begin recovering near the end of 2009. The U.S. economy is likely to grow about 1 percent in the next two years, less than the 3 percent “trend,” he said.

Roubini based his short-term outlook on the worsening condition of the U.S. housing and labor markets, which he called “inextricably linked.” He said a “weak” job market will contribute to another 13 percent to 18 percent drop in house prices, bringing total declines nationally to as much as 45 percent from their peak.

I would add to Roubini’s pessimism that bond market investors as of yet do not share the optimism of their brethren in the equity side of the industry. The run up in yields that brought a 4-handle to the 10 year Treasury appears to have been stopped dead in its tracks, and that maturity has pulled back to the mid threes. If the run-up in yields foreshadowed a burst of optimism in equities, the pull back would suggest that this rally has nearly run its course.

The challenge here is two-fold. The first challenge is to determine how much of the recent equity run is attributable to the weight of evidence that indicates the worst of the downturn is behind us. With the Armageddon trade off the table, some gains were inevitable, just as was the rise in Treasury yields. The more difficult challenge is the strength and pattern of the subsequent recovery. To be sure, one should not ignore the possibility of a blowout quarter here and there, as GDP data can bounce quickly to bounces in underlying data such as a stabilization in auto sales. But will such a bounce reflect fundamental underlying strength? A slow, jobless recovery – my dominant scenario – would most likely produce the seesaw trading we saw in the wake of the tech bubble crash, a pattern that held until the housing bubble gained full traction. Such an outcome looks consistent with the sentiment of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke in this weeks Congressional testimony:

Despite these positive signs, the rate of job loss remains high and the unemployment rate has continued its steep rise. Job insecurity, together with declines in home values and tight credit, is likely to limit gains in consumer spending. The possibility that the recent stabilization in household spending will prove transient is an important downside risk to the outlook.

Later, during questioning, Bernanke reiterated:

What will the recovery look like? Slow. “The American consumer is not going to be the source of a global boom by any means,” Bernanke says.

Sounds like he tends toward the low end of the FOMC’s range of forecasts, and suggests, talk of withdrawal of various monetary accommodation aside, this looks like a reasonable forecast:

BlackRock Inc., the biggest publicly traded U.S. money manager, recommends buying Treasuries maturing in two to five years on expectations the Federal Reserve won’t raise interest rates this year.

“They still see potential downside risks to growth,” Stuart Spodek, co-head of U.S. bonds in New York at BlackRock, said in a Bloomberg Television interview. “The Fed is not going to tighten. It has referenced keeping rates low for an extended period of time.”

With unemployment rates still headed north, it is tough to see the Fed tightening within the next twelve months, if not longer. But will the job market surprise us? No clear indications can be gained from initial unemployment claims data which, although battered by unusual seasonal patterns, overall remains consistent with further drops in nonfarm payrolls. Indeed, this would be consistent with recent patterns of recession. David Altig declares:

…I’m quite sympathetic to DeLong’s theme that the dynamics of U.S. labor markets coming out of recessions appear to have changed starting with the 1990–91 economic contraction. And it might be hard for many people to argue with DeLong’s point that the U.S. economy is likely headed toward another so-called “jobless recovery.” But until more facts are in and we’re able to look back on what transpired, I think we still, at this point, must reasonably count the current run-up in the unemployment rate as a puzzle.

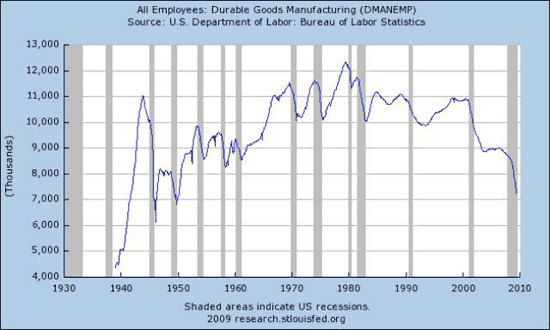

In the comments from my last piece, reader spencer takes a different perspective, noting that forecasters have tended to underestimate the strength of recoveries, and further notes that recent moderate recoveries have followed atypical mild recessions. The current recession, however, is more typical of the pre-1990 variety, and, as such could be expected to yield a rapid recovery. A logical analysis from a long-time observer of business cycles; as always, one should have such an outcome on their continuum of possible events, but I tend not to be particularly sympathetic to the mild recession, mild recovery, big recession, big recovery analogy. It seems to be that a cursory look at the data suggests something very different is happening in the labor market and thus the strength of recoveries since the early 1980s. Look, for example at the pattern of durable goods manufacturing payrolls:

Previous to 1990, durable good jobs snapped back quickly, but that began changing after the 1980 recession, first with a muted rebound, than a slow return after the 1990 recession, and then with no return after the 2000 recession. That lack of rebound alone cost the recovery roughly 2 million jobs – and it seems that if the downturn was only mild, we should have expected these jobs to return. We will lose another 2 million at least by the time the current downturn is complete. Does anyone think these jobs are coming back? Anyone?

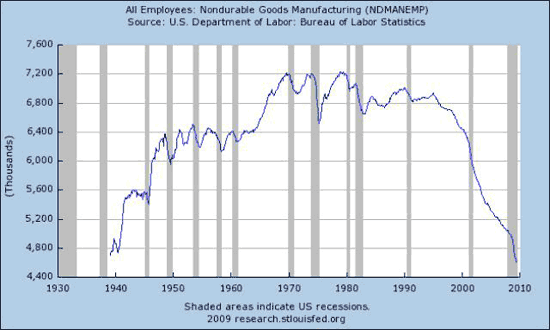

Likewise, nondurable goods manufacturing tells an even worse story:

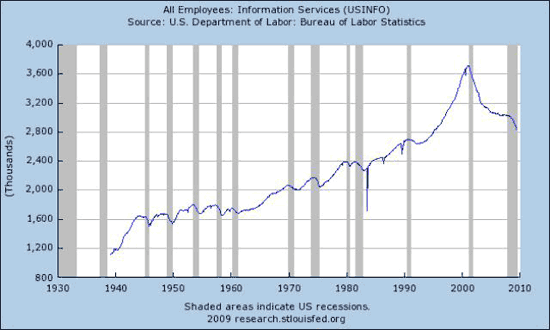

In previous cycles, a rapid bounce, but simply an outright cliff dive since the mid 1990s. Again, do we think this trend will be reversed in the upcoming recovery? Another, albeit smaller sector:

To be sure, information services was coming off a bubble, but stability in the sector remained elusive even at the peak of the recent cycle.

These patterns suggest to me that the last fifteen years has seen intense structural change such that even mild recessions result in permanent dislocations. I have trouble that in the midst of such ongoing structural change a deeper recession will result in a less permanent dislocation. No, I suspect many of these jobs are gone for good, placing an additional weight on the job market during the recovery. Simply put, the danger is that in even a moderate recovery, the remaining expanding sectors will lack sufficient strength to compensate for these permanent losses.

Anticipating the comments, another way some might describe the patterns in the labor markets during recent recessions is that a variety of economic policy decisions by both Democratic and Republican administrations have had the impact of dismembering the industrial base of the US without encouraging the growth of sufficient replacement jobs, thereby throwing the American middle class under the train. That, however, is such a dark interpretation, as opposed to say, cheering the efforts of policymakers to lessen the burden of work on Americans by encouraging foreign nations to forsake their own consumption to provide goods for our citizens.

Bottom Line: I am not convinced that the equity run up confirms much more than the power of low expectations. Indeed, the bond market has yet to follow suit (when I would actually expect it to lead the way). I increasingly think that the debate between V and other shaped recoveries is really a debate over the degree of structural change occurring in the economy. If you believe this is a typical cycle, and that what was demanded and how it was produced is roughly the same after as before the recession, a V-shaped recovery is your likely candidate. If you believe that the current recession is simply intensifying a period of intense structural change, than you are looking for a U or L-shaped recovery. Notably Bernanke, by acknowledging that the US consumer is in no shape to continued its 25 year role as a shaper of global economic trends, seems to be siding with the structural change side of the coin.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply