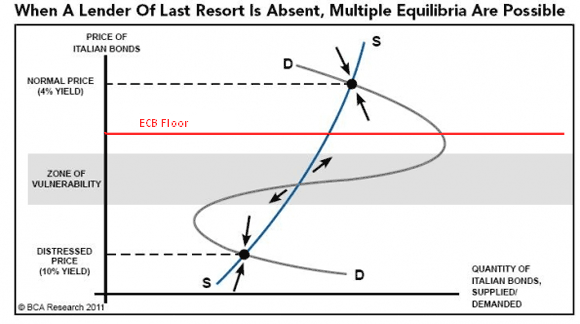

Greg Ip at Free Exchange directs us to a very helpful graph (helpful to those who think about the world in terms of supply and demand curves, anyway) that illustrates how the current situation with eurozone debt can benefit from some non-traditional thinking.

The idea is that the fear currently endemic in eurozone sovereign debt markets means that investors look to the price of bonds for two very different pieces of information. First, as is always the case, the price of bonds tells investors what return they will earn from holding those bonds. So when the price of bonds falls, they look like a better deal and investors can expect to earn a correspondingly higher rate of return, which tends to make the demand for those bonds goes up. That’s the normal, downward-sloping demand curve at the top of the graph.

But right now investors are also extract a second piece of information from the price of those bonds: they see it as a signal about how worried the rest of the bond market is about the probability of default. So once the price gets too low, then even though investors know they will get a good rate of return, they also start to worry that they’ll never get repaid, so a lower price can actually cause demand to fall. That’s the backward bending part of the demand curve noted in the graph as the “zone of vulnerability”. (There are other mechanisms at work to reinforce this negative feedback loop as well, but you get the idea.) The result is that once the price of bonds falls too far, this vicious cycle takes over until a new equilibrium is reached at a very, very low price – the “distressed” price.

This is a helpful way to look at what’s happening in the eurozone bond markets right now, I think. (Note that while this illustration uses Italy as an example, the logic applies equally well to Spain, which is also fundamentally solvent.) But there’s a very clear policy prescription that follows from this analysis, as noted by BCA Research: The ECB has the ability to influence which equilibrium the market settles on.

How can the ECB make sure that the “good” equilibrium is the one that actually pertains? They somehow need to change this picture so the price can never drop below a certain level — the level I’ve added to the picture in red. If the ECB can credibly establish that red line and restrict the market to the upper portion of the graph, then the only possible equilibrium will be the good one. Interest rates stay low, panic is avoided, and minimal additional intervention is required.

So how can the area below the red line be rendered off-limits? There are a couple of ways. First, policy-makers could simply state, repeatedly and loudly, that there is absolutely no possibility of Italy defaulting. If market participants are convinced, then they will no longer look at the price of the bonds as providing information about the probability of default. That’s basically the approach that has been followed by European policy-makers (both within and outside the ECB) to date.

If that doesn’t work, though (and clearly it hasn’t worked very well so far, as investors seem unimpressed by such statements), then more credible statements are needed. The simplest would be for the ECB to make a formal promise that it will simply never let the price fall below the red line. In other words, they could commit to always buying Italian bonds at a price equal to the red line.

Note that this would be very much like an exchange rate floor, in which a central bank states that it will not let a currency fall below a certain limit. That’s exactly what the Swiss central bank promised last month with regard to the euro vis-à-vis the Swiss Franc, for example. Only in this case instead of making a commitment to buy currency at a certain price, the promise would be to buy bonds at a certain price.

For this to work, the ECB’s promise would have to be credible, of course – investors would have to believe that the ECB will actually put its money where its mouth is. But if it is indeed credible, and if the red line (i.e. the bond price floor) is below the good equilibrium price, then it’s very possible that the ECB would not actually have to buy many Italian bonds. The bond market would do most of the work for it, and keep the price of Italian bonds at the good equilibrium. It’s a perfect example of how targeting a price can be a far more effective — and less costly — for a central bank than targeting a certain quantity of intervention.

Of course, it’s unlikely that the ECB would ever follow this economic logic and actually commit to supporting such a bond price floor. The fear among European policy-makers would be that the ECB would have to buy an uncomfortably large amount of Spanish and Italian bonds before the market became convinced that the price floor was indeed binding.

But if the ECB were able to take a deep breath and take this step, it would almost certainly bring about a quick end to the contagion of the eurozone crisis to Italy and Spain. I think it’s a good example of how bold and unconventional economic policy actions could go a long way toward resolving the crisis. And since actual policy responses to the eurozone crisis have been neither bold nor unconventional, it also illustrates why the crisis never seems to end.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply