We received a pretty clear message yesterday – if you are looking for additional monetary stimulus, you need to find a new hobby. Not going to happen. Yes, we know we have said this before, but this time we are serious.

Fed officials simply believe the weakness in the first and second quarters of this year is largely transitory, the impact of commodity prices and tsunami-related supply disruptions. In other words, nothing to see here, move along. The Wall Street Journal had the story time and time again today. Chicago Federal Reserve President Charles Evans, on his growth downgrade:

So I’ve taken some steam off the underlying sustainable rate that we were looking at and we’re pushing that growth out into the second half of this year. But we’re still of the mind that these are relatively transitory phenomena, that the recovery is still going to be continuing to take place and build.

Atlanta Federal Reserve President Dennis Lockhart:

The regional Fed president, who is not a voting member of the monetary policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee, added Tuesday that he is “frustrated” with the pace of economic recovery.

Still, the string of disappointing economic data “is no reason to panic” as “recoveries rarely play out smoothly.”

In fact, given the litany of unforeseen events–ranging from the Japanese earthquake and Middle East conflict to the weak domestic housing market–Lockhart said the U.S. economy has shown “pretty impressive resilience.”

And Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke:

U.S. economic growth so far this year looks to have been somewhat slower than expected. Aggregate output increased at only 1.8 percent at an annual rate in the first quarter, and supply chain disruptions associated with the earthquake and tsunami in Japan are hampering economic activity this quarter. A number of indicators also suggest some loss of momentum in the labor market in recent weeks. We are, of course, monitoring these developments. That said, with the effects of the Japanese disaster on manufacturing output likely to dissipate in coming months, and with some moderation in gasoline prices in prospect, growth seems likely to pick up somewhat in the second half of the year.

Did they make it clear enough? DON’T PANIC! It is all under control. Interestingly, Bernanke further suggests that not only will they do no more, no more can be done:

The U.S. economy is recovering from both the worst financial crisis and the most severe housing bust since the Great Depression, and it faces additional headwinds ranging from the effects of the Japanese disaster to global pressures in commodity markets. In this context, monetary policy cannot be a panacea. Still, the Federal Reserve’s actions in recent years have doubtless helped stabilize the financial system, ease credit and financial conditions, guard against deflation, and promote economic recovery. All of this has been accomplished, I should note, at no net cost to the federal budget or to the U.S. taxpayer.

The last line should erase any doubt the Federal Reserve is now under the sway of political pressure. Note also Bernanke’s long defense of the Fed on the issue of commodity prices – clearly he is getting grief on this point. Would he even be willing to chance that he is wrong?

But not only is monetary policy out of the question at this juncture, he also argues that fiscal policy should be off the table as well:

The prospect of increasing fiscal drag on the recovery highlights one of the many difficult tradeoffs faced by fiscal policymakers: If the nation is to have a healthy economic future, policymakers urgently need to put the federal government’s finances on a sustainable trajectory. But, on the other hand, a sharp fiscal consolidation focused on the very near term could be self-defeating if it were to undercut the still-fragile recovery. The solution to this dilemma, I believe, lies in recognizing that our nation’s fiscal problems are inherently long-term in nature. Consequently, the appropriate response is to move quickly to enact a credible, long-term plan for fiscal consolidation. By taking decisions today that lead to fiscal consolidation over a longer horizon, policymakers can avoid a sudden fiscal contraction that could put the recovery at risk. At the same time, establishing a credible plan for reducing future deficits now would not only enhance economic performance in the long run, but could also yield near-term benefits by leading to lower long-term interest rates and increased consumer and business confidence.

Bernanke sees the threat posed by excessive short-term fiscal consolidation, but offers no suggestion that perhaps more short-term stimulus is still needed – that to close the output gap, fiscal authorities need to move more spending from the future to the present. But given the expansion of the balance sheet, I think Federal Reserve officials fear this road, as it creates the impression of deficit monetization. So, no stimulus, monetary or fiscal.

Finally, Dallas Federal Reserve President Richard Fisher noted:

The central banker noted consumers and firms are still traumatized by the economic and financial difficulties of recent years, and that’s part of why growth levels are still struggling. But he does expect activity to pick up: “The next half of the year will have better growth than we’ve seen recently,” Fisher said. “It’s not going to be robust” and he expects to see a “jerky motion” to activity.

The description of a recovery that is jerky and lacking robustness brings to mind something Greg Ip said last week:

Still, I was recently reminded by someone who lived through Japan’s lost decade that America is qualitatively, if not quantitatively, following the same script. That means we will often think robust, above-trend growth has begun, only to see it snuffed out by the inexorable post-bubble deleveraging. Japan offers another sobering lesson: its policy flexibility was heavily circumscribed by politics. Bail-outs, deficits and quantitative easing were no more popular in Japan than in America today. Japanese officials are far too polite to say “I told you so.” But they could.

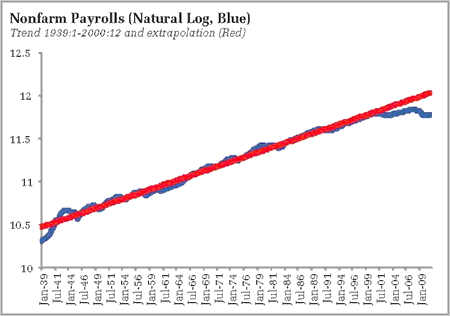

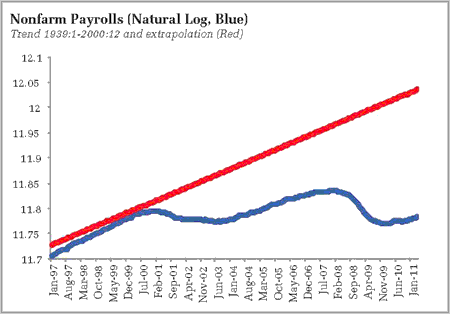

And it is worth noting that while we think about “a lost decade” over the next ten years, the past ten years was already a lost decade for many:

Bottom Line: Federal Reserve officials accept the economy at face value – growth is slower than they would like, unemployment higher than they would like, but policymakers, fiscal and monetary, believe they are pretty much out of bullets. Unless the economy slips badly, don’t expect any more from us. Which leaves the rest of us hoping – against hope, if recent history is any guide – that the economy regains its footing in the second half of the year.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply