In a recent issue of Economic Synopsis, our colleague Dan Thornton of the St. Louis Fed questions the usefulness of the traditional core inflation statistics—the consumer price index (CPI), or the personal consumption expenditure price index that strips out food and energy costs. Specifically, Dan asks whether the core inflation statistic is a better predictor of future inflation over the medium term (say, the next two or three years), than the headline inflation statistic. His conclusion is that:

“[F]or the most recent period, there is no compelling evidence that core inflation is a better predictor of future headline inflation over the medium term.”

But Dan also invites the following:

“[I]n the interest of greater transparency and to allow the public to better understand its focus on core measures, the FOMC [Federal Open Market Committee] should provide evidence of the superior forecasting performance of the core measure it uses.”

Well, of course neither writer of this blog post is on the FOMC, and equally obvious is the fact that we don’t speak for anyone who is. Moreover, we’re not very big fans of the traditional core measures, and we much prefer trimmed-mean estimators of inflation when thinking about recent price behavior.

Nevertheless, we’d like to attempt an answer to Dan’s call, even if it wasn’t aimed at us.

Here’s the experiment run by Dan: He used the past 36-month trend in the traditional core inflation measure and the ordinary headline inflation measure and tested which one most accurately predicted the next 36 months of headline inflation. He found that they’re about the same. A similar look at 24-month trends yielded a similar result.

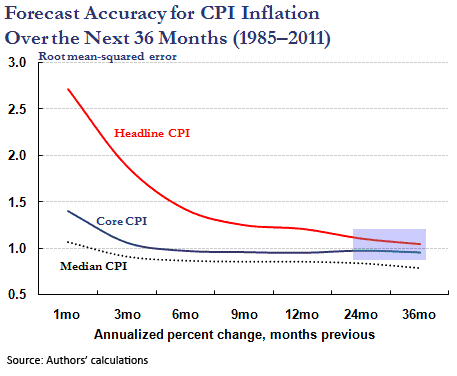

The upshot of these experiments can be seen in the figure below (which is a figure of our construction, not his).

The chart shows how accurately we can predict headline CPI inflation over the next three years using only headline CPI price data or, alternatively, using only core CPI price data. The essence of the conclusion reached in the Economic Synopsis is summarized within the shaded box. The forecast accuracy of the two- and three-year trends of the core CPI price measure doesn’t seem to be a significant improvement to the plain-vanilla headline CPI.

But we wonder whether the contribution of the core inflation statistic is being accurately reflected in this experiment. For us, the power of a core inflation measure—whether it be the traditional ex-food and energy measure, or some more statistical construct like the trimmed-mean estimators—can’t be seen by comparing data trends of this sort. The volatility of an inflation statistic, what we would characterize as “noise,” dissipates rather quickly, generally within a few months (although for food and energy, it could play out over a longer period of time, we understand).

At issue is how much the most recent month’s or quarter’s inflation data should inform one’s thinking about the future path of inflation. Implicit in the experiments reported above is that they shouldn’t—well, only as much as the most recent monthly or quarterly data influence the trend of the past two or three years.

It may be that the most recent monthly or even quarterly data are so noisy that they have nothing useful to contribute to our perception of the future inflation trend. But then again, an experiment that assumes there is no useful information in the most recent inflation data does not necessarily make it so.

We’d like to call your attention to the remainder of the figure above, where we ask the question, what happens if you try to predict headline CPI inflation over the next three years using only the most recent price data? For example, what if we restrict ourselves to looking only at the most recent month’s CPI report? What we see is that the core inflation statistic provides a much improved prediction of the future inflation trend compared to the headline measure. Specifically, forecast accuracy is improved by nearly 50 percent if you use the core inflation measure. (For you wonks, the root mean square error, or RMSE, of the core CPI prediction is about 1.4 percent, compared with a RMSE of 2.7 percent for headline CPI inflation.)

Now consider the behavior of CPI prices over the past three months. How informative of the future inflation trend are these prices? Well, the accuracy of the headline inflation statistic improves relative to the one-month percent change because averaging the data over time in this way necessarily reduces the transitory fluctuations in the data. But again, the three-month core CPI price statistic provides a much better prediction of future headline inflation than does the three-month trend in the ordinary CPI statistic. In other words, if you’re wondering what the past-three months of data tell you about developing inflation pressure, you’re much better off considering the core statistic than you are the headline number.

Here’s another observation we’d like to make: The most recent three-month trend in the core CPI inflation measure appears to be a more accurate predictor of future inflation than the 12-month headline CPI trend. Moreover, the three-month trend in the core measure is roughly as accurate as its longer-term trends. This observation suggests that paying attention to the core measure may allow you to spot changes in the inflation trend much more quickly than using headline alone.

Again, to be clear, we aren’t endorsing the core inflation statistic. We’re fans of trimmed-mean estimators and think they do an even better job of informing thinking about what the most recent price data tell us about the likely future path of inflation. (As evidence, we included in the chart above the same forecasting results for the median CPI.) We only want to make one simple point—the usefulness of a core inflation measure is best seen in the monthly and quarterly intervals that span FOMC meetings, not in the two- or three-year trends which are, by construction, largely silent about the most recent data.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply