I confess to be more than a little surprised when yesterday’s morning reading turned up the following headline, from Bloomberg’s Bob Ivry:

“Fed Gave Banks Crisis Gains on Secretive Loans Low as 0.01%”

The crux of the story found its way to the Wall Street Journal‘s Real Times Economics blog:

“Credit Suisse Group AG, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc each borrowed at least $30 billion in 2008 from a Federal Reserve emergency lending program whose details weren’t revealed to shareholders, members of Congress or the public. The $80 billion initiative, called single-tranche open-market operations, or ST OMO, made 28-day loans from March through December 2008, a period in which confidence in global credit markets collapsed after the Sept. 15 bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. Units of 20 banks were required to bid at auctions for the cash. They paid interest rates as low as 0.01 percent that December, when the Fed’s main lending facility charged 0.5 percent.”

I think a couple of clarifying points are in order. First, these transactions were hardly, in my view, “secretive.” On March 7, 2008, the following was posted on the New York Fed’s website (with similar information provided by the Board of Governors):

“The Federal Reserve has announced that the Open Market Trading Desk will conduct a series of term repurchase (RP) transactions that are expected to cumulate to $100 billion outstanding. This initiative is intended to address heightened pressures in term funding markets. These transactions will be conducted as 28-day term RP agreements in which primary dealers may elect to deliver as collateral any of the types of securities—Treasury, agency debt, or agency mortgage-backed securities—that are eligible as collateral in its conventional RP operations.”

The magic words in the Bloomberg piece are apparently “details weren’t revealed.” While it is true that specific transactions with specific institutions were not published in real time, the overall results of the auctions (both total purchases and the lowest interest rate paid) were posted each day (as noted in the Bloomberg article), and the list of potential counterparties (the primary dealers) was (and is) available for all to see. I suppose we could have a reasonable debate about how much information is required to support the claim that “details” were made available. But I have a hard time with the notion that publicly announcing the program, offering details on size and prices in each day’s transactions, and providing general information about the entities in the game constitutes “secretive.”

Another aspect of the Bloomberg piece that I question is the claim that the transactions were “loans” provided under an “emergency lending program.” That language is quite imprecise and evokes the thought of the lending programs that relied on the authority granted under “unusual and exigent circumstances” by section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act.

The Bloomberg article does not help in avoiding possible confusion on this point by including this passage:

“Congress overlooked ST OMO when lawmakers required the central bank to publish its emergency lending data last year under the Dodd-Frank law.”

But as the New York Fed’s public notice made clear at the time, this was not outside of the Fed’s standard authorities—and not unprecedented (emphasis added):

“When the Desk arranges its conventional RPs, it accepts propositions from dealers in three collateral ‘tranches.’ In the first tranche, dealers may pledge only Treasury securities. In the second tranche, dealers have the option to pledge federal agency debt in addition to Treasury securities. In the third tranche, dealers have the option to pledge mortgage-backed securities issued or fully guaranteed by federal agencies in addition to federal agency debt or Treasury securities. With the special ‘single-tranche’ RPs announced today, dealers have the option to pledge either mortgage-backed securities issued or fully guaranteed by federal agencies, federal agency debt, or Treasury securities. The Desk has arranged single-tranche transactions from time to time in the past.“

Finally, identifying the one auction where the Fed “paid interest rates as low as 0.01 percent” is misleading. To begin with, the 0.01 percent refers to the so called “stop-out” rate, which is the lowest rate paid by bidders in any particular auction. The operations in question were multi-price auctions, so the lowest rate cannot be assumed to be the average rate paid on the repo transactions. In any event, the program was terminated after two auctions when the stop-out rate hit the very low levels the Bloomberg article referred to.

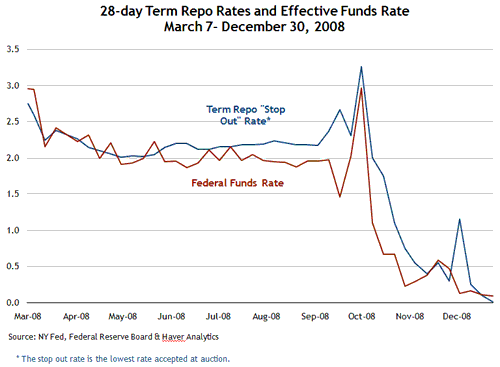

More generally, the auction rates in these ST OMOs tracked short-term funding rates over the course of the program’s existence:

The interest rates associated with all operations obviously fell as the provision of market liquidity became more aggressive after the failure of Lehman Brothers. You are free to object to that response, but singling out ST OMO as secretive or special in anyway isn’t, in my opinion, justified.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply