Two decades of spectacular growth and industrialisation in emerging economies has transformed the world economy, presenting US trade policy with new challenges. This is the first of two columns that consider one aspect of the new challenges – the ways in which the Obama Administration can secure better access for American exporters.

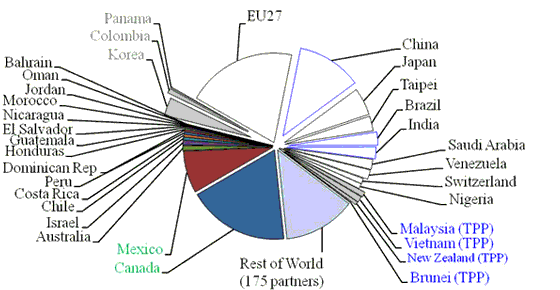

When thinking about American market access – i.e. the tariffs that hinder US exports – the place to start is the markets that matter most to US exporters. About 40% of US exports go to rich nations. The rest is spread widely (see Figure 1). China, Taipei, Brazil, and India together absorb 19% with China accounting for the lion’s share (12% of US exports).

Figure 1. US export markets with and without FTAs

Notes: Coloured slices indicate US partners with FTAs. Listed nations either have and FTA, or account for more than 9/10th of 1% of US exports. Source: USITC online database.

What tariffs do US exports face?

Since 1947, America pursued better market access in GATT multilateral trade negotiations known as “Rounds”. This worked for rich nations, but not for developing nations.

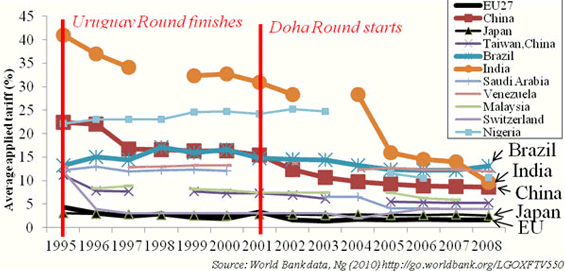

Figure 2 shows that average tariffs in Japan and the EU are under 3%, but others are three to four times higher.

The rich/poor asymmetry in tariffs was done on purpose. Motivated by the now-antiquated thinking that tariffs help development, GATT explicitly granted developing nations free-rider status in 1964. Practicality was another prime motive. Until recently, all developing-nation markets were small, and all commercially important nations were developed. Absolving developing nations from tariff cuts in GATT Rounds allowed the US and a handful of other rich nations to run the GATT – despite its consensual decision-making procedures. The rich nations negotiated a package of tariff cuts that suited them; developing nations went along as free-riders.

Figure 2. Tariff averages in major US export markets without free trade agreements

Source: World Bank online database. Nations listed account for a least 1% of US exports but don’t have an FTA.

From the mid-1990s, two new routes to improving US market access opened up.

- Free trade agreements (the US now has 17).

This route is, so far, unimportant apart from NAFTA which covers 26% of US exports; all the other FTAs combined cover just 6.6% (Figure 1).

- Unilateral tariff cutting by developing nations.

Starting in the late 1980s, developing nations realised that tariffs – especially on industrial parts and components – hindered their industrialisation, and so began to cut them unilaterally. For example, India unilaterally lowered its applied tariff average from 40% in 1995 to about 10% today.

This reversed the free riding. US exporters became the free riders on the emerging economies’ tariff reductions. Much of this happened while the Doha Round talks dragged on (Figure 2). US trade policy had nothing to do with it. It was just good luck for US policymakers. Figure 2 shows, however, that the luck is running out. Unilateralism has moved slower in recent years.

Improving US market access going forward

US industrial exporters still face major tariffs in emerging markets, and US food exporters face major barriers in most of the world’s largest markets. What is the US doing to get these down?

All US trade policy was frozen during President Obama’s first two years in office (to help keep anti-trade Democrats on board for healthcare reform, etc). It was unfrozen when Republicans won the lower house and the Administration started promoting US market access in three ways.

- Getting Congress to approve the three FTAs that President Bush signed but couldn’t get through Congress.

- Embracing a prospective FTA with 8 Asia-Pacific partners (Trans-Pacific Partnership).

- Pushing for a conclusion of the Doha Round.

Because market access turns on market size, the Doha Round is the only one of these three that is likely to significantly improve market access for US exporters before 2020 (although TPP will be important for non-market access reasons like setting the rules on 21st century trade issues).

The 3 pending FTAs and the potential Trans-Pacific Partnership members cover small markets (Figure 1). In total, they will apply to only 6.2% of US exports, with Korea accounting for more than half of this. The 3 FTAs cover 4.3% and the 8 TPP members only 1.9% more when double counting is eliminated (the US already has FTAs with 4 of the TPP partners).

A good Doha outcome, by contrast, would cover almost all of US exports – including China, Taipei, Brazil and India. The reason is that developing nations’ free ride has been cancelled in the Doha Round. It is the first Round where developing nations are required to play reciprocally in a substantial way (although they are asked to make less strenuous cuts).

In all, the Doha tariff cuts would be the biggest market opening initiative ever signed by the US (HLTE 2010).1

Obama is closing off the Doha route

The Round, however, is in dire peril and Obama seems to be getting ready to let it die. The current blockage turns on the gap between the US and China and other emerging markets. The US wants them to lower their tariffs to zero on about half of industrial imports in exchange for the US doing the same. As Figure 2 shows, US tariff levels start far lower so this zero-for-zero would mean the US cuts its tariff average by many fewer percentage points than China, India and Brazil. China et al have refused, so the Doha Round is stuck.

Remarks from the US and Chinese Ambassadors to the WTO last week suggest that neither is unwilling to make the compromises necessary to keep the Doha talks moving. The US Ambassador pointedly argued that the impasse on industrial tariffs was not the only one (others are likely in agriculture and services) – as if to suggest that compromise on the current impasse would be futile (USTR 2011).

The Obama Administration has not clearly articulated the reasons for its stance. Talking with WTO Ambassadors from other nations and US trade policy experts in Washington, I gather that there are two key concerns:

- The tariff-leverage argument.

Without a zero-for-zero deal, the Doha cuts would lower US tariffs to the point where it would have few bargaining chips left while leaving emerging market with many. The fear is of a lasting tariff asymmetry vis-à-vis China et al. As the US Ambassador said, Doha would “will set the terms of trade for decades to come and an agreement that does not reflect 21st century realities will contribute neither to the strength of the global trading system nor to the long-term viability of this institution.”

- Too little new market access.

Some estimates suggest that the Doha cuts would provide little new market access (i.e. above and beyond the free-ride access that US exporters have enjoyed since the Round started; see Figure 2). This might or might not be true. One of Doha’s big problems is that a nation’s concessions are clear, but its market access gains are unclear (Schwab 2011). Evenett (2011) argues that US exporters might be mis-thinking the numbers.

Next column

The next column, to be posted tomorrow, will address American options for improving market access if Doha is allowed to fail this year.

References

•Evenett, Simon (2011). “The dubious hold-up over Non-Agriculture Market Access (NAMA)”, in Baldwin and Evenett (eds.), Why World Leaders Must Resist the False Promise of a Doha Delay, A VoxEU.org Publication.

•Schwab, Susan (2011). “After Doha: Why the negotiations are doomed and what we should do about it”, Foreign Affairs, May/June.

•USTR (2011). “Statement of Ambassador Michael Punke US Permanent Representative to the World Trade Organization”, 29 April.

___________________________

1The least developed nations don’t have to do anything, but their markets are trivial in terms of US exports.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply