The Trade Deficit rose in March to $48.18 billion from $45.44 billion in January (revised down from $45.76 billion. The rise in the trade deficit is bad news for the economy, and the level is very dangerous.

For the month it was up 6.0%, and it was worse than the $47.7 billion consensus expectation. On a year-over-year basis, the total trade deficit was up 21.9% from $39.51 billion a year ago. The trade balance has two major parts: trade in goods and trade in services. America’s problem is always on the goods side; we actually routinely have a small surplus in services.

Relative to February, the goods deficit rose to $62.11 billion from $59.10 billion. That is a month-to-month increase of 5.1%. Relative to a year ago, the goods deficit was up 18.8% from $52.26 billion. The Service surplus was up slightly from February to $13.93 billion from $13.66 billion. Relative to a year ago it is up 9.3% from $12.75 billion. Exports of goods rose by $7.13 billion, or 6.1%, for the month to $124.93 billion. Relative to a year ago, goods exports are up 18.7%.

On Pace to Double Exports

In other words, we are easily on pace to meet President Obama’s goal of doubling exports of goods over the next five years. Service exports, on the other hand, were up only 1.1% for the month, and were up 6.1% year over year, which is well short of the pace needed to double over five years (just under 15%). Total exports rose 3.4% for the month and are up 14.9%, right on the pace needed to double over five years.

Doubling exports over five years is all well and good, but not if we also double our imports over the same timeframe. After all, it is net exports which are important to GDP growth, and to employment. The monthly numbers on the import side were not encouraging in this regard, as goods imports rose by $10.14 billion, or 5.7% to $187.04 billion.

Relative to a year ago, goods imports were up by $29.51 billion, or by 18.7%. At that pace, they are clearly on the pace needed to more than double over five years. Service imports were up by $26 million on the month or 0.8%. Total imports rose by $10.41 billion or 4.9% for the month to $220.85 billion and are up 16.4% year over year.

What This Means for the Trade Deficit

Given that imports are starting from a higher base, doubling both imports and exports would mean a substantial increase in the size of the trade deficit. Put another way, in March we bought from abroad $1.50 worth of goods for every dollar of goods we sold. That was unchanged from February and from a year ago. Including services, we imported $1.28 for every dollar we exported, unchanged from February and up from $1.26 a year ago.

For all of 2010, the total trade deficit was up an astounding 32.8% to $497.82 billion, with the goods deficit up 27.5% to $646.54 billion, somewhat offset by the service sector surplus rising 12.0% to $147.82 billion. Trade in goods simply swamps trade in services, even though services are a much larger part of the overall economy.

So far in 2011, the total trade deficit is up 23.5% from the first three months of 2010. The goods deficit is up 20.3%, offset by a 10.5% increase in the service surplus. Year to date, our deficit with the rest of the world is $140.59 billion, up from $113.87 billion in the first quarter of 2010.

Exports to Continue Rising?

All things being equal, it is better to see trade going up than down. We want to see both exports and imports growing, but given the massive deficit we are running, we need to have exports rise dramatically faster than imports, or actually see imports fall. From a purely nationalistic point of view, rising exports or falling imports are roughly equivalent in terms of economic growth. Falling imports, though, implies economic pain in some other countries.

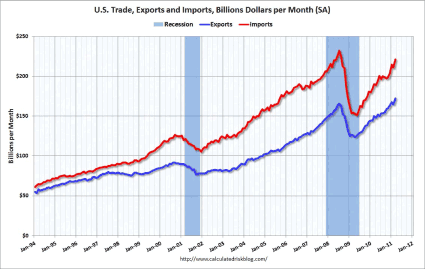

Thus all else being equal, it would be better if most of the improvement in the trade deficit came from rising exports rather than falling imports. A big part of what made the Great Recession into a global downturn was an absolute collapse in global trade. This can clearly be seen in the long-term graph of our imports and exports below (from http://www.calculatedriskblog.com).

Falling imports and exports are clearly associated with recessions. In the Great Recession our imports collapsed faster than our exports, and so we had a very big improvement in the trade deficit.

Falling imports were just about the only thing keeping the economy on life support during those dark days. For example, in the first quarter of 2009 the smaller trade deficit increased growth by 2.64%. If not for that, the economy would have shrunk by 9.0% instead of by 6.4%.

Therefore, growing world trade is a good thing, but not if it comes at the expense of an ever-rising U.S. trade deficit. In other words, all things are not equal. Had it not been for a dramatic deterioration in the trade deficit in the second quarter of last year, GDP growth would have been over 5.2%, not 1.7%. In the third quarter it would have been 4.3% rather than 2.6%.

The drop in the trade deficit in October and November was one of the most powerful forces behind the growth we saw in the fourth quarter. Without the improvement in net exports, the economy would have actually shrunk by 0.2%, rather than growing by 3.1%.

Trade turned against the economy again in the first quarter, but only slightly, subtracting 0.08 points from growth. Still the swing from being a big contributor in the fourth quarter to being essentially a non-factor in the first quarter more than explains the overall slowdown in growth from 3.1% to 1.8%.

Clearly it matters a great deal if the trade deficit is growing or shrinking. The higher-than-expected trade deficit for March would indicate that (all else being equal) that the next look at first quarter GDP will be revised down.

Trade Deficit Far More Serious

The trade deficit is a far more serious economic problem, particularly in the short-to-medium term, than is the budget deficit. The trade deficit is directly responsible for the increase in the country’s indebtedness to the rest of the world, not the budget deficit. That is not just a matter of opinion, it is an accounting identity.

Think about it this way: during WWII the Federal Government ran budget deficits that were FAR larger as a percentage of GDP than we are running today, but we emerged from the war the biggest net creditor to the rest of the world that the world had ever seen up to that point. Then the Federal government owed a lot of money, but it owed it to U.S. citizens, not to foreign governments. Slowly but surely the trade deficit is bankrupting the country.

While most of the foreign debt is in T-notes, try think of it as if we were selling off companies instead of T-notes. This month’s trade deficit is the equivalent of the country selling off US Bancorp (USB), while last month’s deficit was the equivalent of selling off Medtronic (MDT). How long would it take before every major company in the U.S. was in foreign hands if this keeps up? Put another way, the 2010 trade deficit has totaled $497.82 billion, which is 64% what all the firms in the S&P 500 earned, worldwide, in 2010.

Who Imports More – Rich or Poor?

The goods deficit has two major parts: that which is due to our oil addiction and that which is due to all the stuff that line the shelves of Wal-Mart (WMT). Of the total goods deficit of $62.11 billion, $31.29 billion — 50.3% — is due to our oil addition.

Relative to the overall trade deficit, our oil addiction is 64.9% of the problem. For all of 2010, we ran a $265.12 billion deficit just from petroleum. That is equivalent to the combined market capitalizations of Chevron (CVX), Marathon Oil (MRO) and Apache Energy (APA).

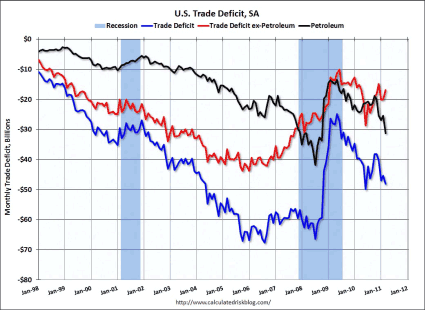

The second graph (also from http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/) breaks down the deficit into its oil and non-oil parts over time. It shows that the overall trade deficit (blue line) deteriorated sharply from 1998 to mid-2005 and then remained at just plain awful levels until the financial meltdown caused world trade to come to a screeching halt.

That caused a major (but unfortunately short-lived) improvement in the overall deficit. However, the stabilization in the non-oil deficit started about two years earlier, though that was offset by the effects of soaring oil prices which caused the oil side of the deficit to deteriorate sharply.

The monthly deterioration in the goods deficit came entirely from the oil side. Given that oil prices continued to rise in April, that means that the trade deficit will probably rise again in April, but that there is hope for the May numbers (provided oil prices don’t shoot up again). The non-oil deficit was actually down up by $2.96 billion or 9.0%.

Relative to a year ago, the non-oil deficit was up 12.1% or $3.21 billion. On the oil side, the deficit soared to $31.29 billion from $25.48 billion in February, and 28.0% above the $24.44 billion level of a year ago.

Getting Off Oil Will Pay Huge Rewards

The oil side should be the low hanging fruit to bring down the overall trade deficit and thus help spur economic growth. Oil is primarily (70%) used as a transportation fuel. The technology exists and is widely used abroad to use natural gas (NG) to power cars and trucks.

There are over 12 million NG vehicles on the road worldwide, but only 1.2% of those are in the U.S. Thanks to the emerging shale plays, we have ample domestic supplies of natural gas, and on a per BTU basis, natural gas is selling for the equivalent of oil at $25.08 per barrel.

We need to get past the “chicken and the egg” problem of nobody wanting to buy a natural gas-powered vehicle because there are no convenient places to refuel, and gas stations’ reluctance to install refueling stations for NG powered vehicles since there are not many of them on the road.

Not only would such a move save money for drivers in the long run (there is an upfront capital cost as natural gas powered engines are more expensive than regular gasoline powered engines), but it would substantially reduce our trade deficit. Since it is a domestically produced fuel (and most of what we do import, we import from Canada) there is also a huge national security argument for moving to using more NG.

The dollars we send abroad to pay for oil imports are simply the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the overall cost of oil. A substantial portion of the Pentagon budget is devoted to keeping the oil flowing in the Middle East and the sea routes open. While I don’t think that oil was the only reason for our being in Iraq, it is clearly a significant factor.

Natural gas is also a much cleaner fuel and emits far less CO2 than does gasoline (and almost no other pollutants other than CO2). Thus it would be a very useful step towards stopping global warming (although it is important to make sure that methane does not leak during the drilling process since it is a much more potent greenhouse gas, molecule for molecule, than is CO2).

Doing this, especially breaking the “chicken and the egg” problem will take federal government leadership. The benefits for the economy however, would be huge.

It seems inevitable to me that this will eventually happen — and when it does, it will be a great boon to major natural gas producers like Chesapeake (CHK) and EnCana (ECA). The timing of it happening is very uncertain, but the sooner it happens, the better.

I don’t want to minimize the cost of doing so, particularly in terms of water quality. We need to do more research on the chemicals used in fracking operations to get at the shale gas (starting with getting rid of the trade secrets provision that allows the firms to hide exactly what they are putting into the ground and potentially the groundwater). Strong environmental regulation is needed of the shale gas operations, but it should be possible to both protect the environment and get the gas out of the ground.

Yes there would still be an environmental risk, but we need to take some risks, and the risk of not using the natural gas resource seems greater. It strikes me as a tradeoff worth making.

Dollar Needs to Fall vs. Yuan

The best thing that could happen to help on the non-oil side of the trade deficit would be for the dollar to fall (particularly against the Chinese Yuan, but against other currencies as well). The decline of the dollar is starting to have a beneficial effect.

A strong dollar not only makes imports cheaper, it makes our exports less attractive. However, a weak dollar will not do anything for the oil side of the deficit. There are few correlations that are stronger in the market over the last few years than oil prices rising when the dollar falls and vice versa. Not quite to the relationship between rising bond yields and falling bond prices, but pretty close.

It is not just a direct effect of say our being able to sell more goods in Japan because the dollar is weak relative to the yen, but U.S. companies are often in direct competition with Japanese or European companies in selling to third countries. For example, both General Electric (GE) and Siemens (SI) make MRI machines for hospitals. Assuming that they were of roughly equal quality, then when the Euro rises sharply against the Dollar, GE is going to be able to undercut Siemens for export orders to China.

By country, we ran some small trade surpluses with Hong Kong, Singapore and Australia, but we continue to run large deficits with most of our other trading partners. The biggest deficit by far is with China, the source of many of the goods on the shelves of Wal-Mart. It fell this month, to $18.1 billion from $18.8 billion in February and from $23.3 billion in January. That is still 36.8% of our overall trade deficit.

While China has agreed to let the Yuan appreciate, so far it has done so at only a glacial pace. However, higher inflation in China than in the U.S. means that the real exchange rate is improving somewhat faster than that.

Other Deficit Updates

Our deficit with the European Union rose this month to $9.0 billion, from $6.9 billion. We saw an increase in our trade deficit with OPEC ($10.8 billion vs. $9.4 billion). Our trade deficit with Mexico rose to $6.2 billion from $5.3 billion, while the deficit with Canada (by far our largest trading partner) fell to $2.8 billion from $3.0 billion. Canada is our single largest foreign oil supplier. The deficit with Japan rose to $6.1 from $5.2 billion. Given the effects to the disaster in Japan, I would expect a sharp fall in our bilateral deficit with Japan next month.

Disappointing & Worse Than Expected

Overall, this was a disappointing report, and worse than expected. The principal cause was higher oil prices, and we should expected significant further deterioration on that front in April. The non-oil side was encouraging, and shows that the weaker dollar is starting to help.

Stepping back a bit, the problem is decidedly not on the export side. Refer back to the first graph and you will see that the slope of the export line is much steeper than it was in the previous two economic expansions. The problem is on the import side, which is rising at an even faster rate.

It is the change in the trade deficit that drives GDP growth, not the level. As long as the trade deficit shrinks, it will add to overall growth, even if the level is still awful. A rising trade deficit shrinks the economy on just about a dollar-for-dollar basis.

Getting the trade deficit under control has to be one of the top economic priorities. If we do, economic growth will be much higher, and we might actually start to see some significant job creation. With the rise in employment will come higher tax revenues which will help bring the budget deficit under control.

To do that we need to do two things, first get our oil addiction under control. The second is that “King Dollar” is a tyrant and needs to meet the same fate as Charles I and Louis XVI — off with his head!

The Fed’s Role

The Fed seems to understand this, and a weaker dollar is one of the more important mechanisms through which quantitative easing will tend to stimulate the real economy (and is the key reason why we are getting so much criticism about it from the rest of the world, as a decrease in our trade deficit would mean a corresponding decrease in they trade surpluses). The U.S. can simply no longer afford to be the importer of last resort for the rest of the world.

As worldwide, trade deficits and surpluses have to sum to zero (barring the opening of major trade routes to Alpha Centari), a reduction in the U.S. trade deficit has to mean that the trade surpluses of other countries has to fall (or other deficit countries have to run even bigger deficits).

Right now every country in the world is trying to maximize exports and minimize imports. We have to fight that battle as well, but it is a fight where we have been getting our butts kicked for decades now. Continuing to lose the fight could result in near fatal damage to our economy and way of life. As I said before, the trade deficit is a far bigger economic problem than the budget deficit.

Inflation Concerns?

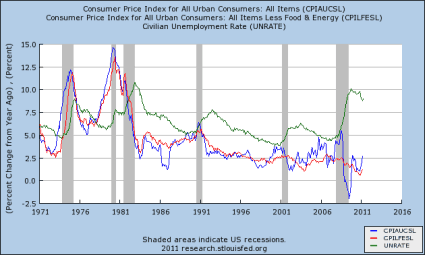

The downside of a weaker dollar is that it will tend to push up inflation. However, at this point, inflation is not a major problem — particularly core inflation, the non-food and energy part of inflation. The final graph shows that core inflation (CPI), which is what the Federal Reserve tends to focus on, is at historic lows. Even including food and energy prices (red line) year over year inflation is still below where it has been for the vast majority of my life.

Solving (or even making substantial progress) on the trade deficit would do wonders in helping to resolve the most important problem in the economy right now — the 9.0% unemployment rate. Seriously folks, look at the graph below, and tell me how anyone could come to the conclusion that right now the Fed should be more concerned about the inflation side of their mandate than they are about the full employment side.

MEDTRONIC (MDT): Free Stock Analysis Report

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply