Just how much has the U.S. government promised to pay?

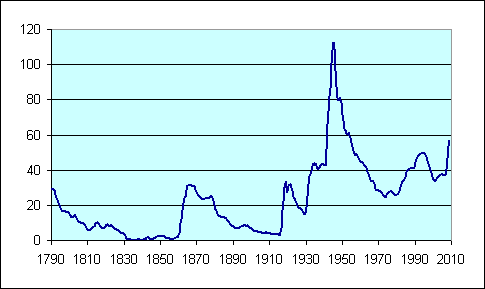

Total public debt outstanding of the U.S. Federal Government is currently $11,490 billion, or $124,000 per taxpayer. But a fair chunk of that total public debt– $4,350 B to be exact– is money that the government owes to itself, about half to the Social Security Trust Fund, and the remainder to other government accounts such as Civil Service Retirement and Disability, Military Retirement, Medicare, and Unemployment Insurance Trust Funds. The debt actually held by the public is “only” $7,140 billion, which amounts to half of last year’s GDP. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that debt held by the public will rise to 56.6% of GDP by the end of this year. That will put the number well above the peaks reached in the Revolutionary War, Civil War, World War I, or the Reagan years, though still significantly below the debt run up from World War II.

Figure 1. Federal debt held by the public as a percent of GDP, 1790-2008, and projected for 2009. Data source: Congressional Budget Office.

But is it correct to subtract off the $4.3 trillion that the government owes “to itself”? These intragovernmental accounting entries represent an intention of the government to deliver real resources to certain parties, such as retirees, at a future date, so perhaps we should include them in a reckoning of all that the government has promised to pay. On the other hand, given what is currently promised, and given trends in the aging population and rising medical costs, if benefit formulas continue as present, the amount that the government would be obligated to deliver far exceeds the sums acknowledged in the intragovernmental debt accounts or what could be covered with future tax revenues.

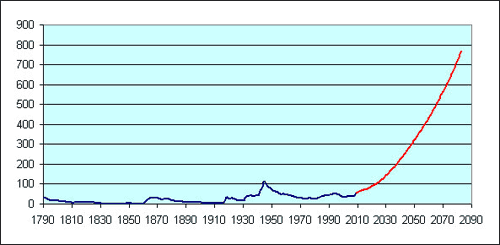

One calculation that the CBO has performed is what they call an “alternative fiscal scenario” representing

one interpretation of what it would mean to continue today’s underlying fiscal policy. This scenario deviates from CBO’s baseline even during the next 10 years because it incorporates some policy changes that are widely expected to occur and that policymakers have regularly made in the past.

According to the CBO, in the absence of a significant increase in taxes above historical rates or change in benefit policies, growth in Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid would quickly produce an explosion of federal debt.

Figure 2. Debt held by the public as a percent of GDP, 1790-2008, and projected for 2009-2083 under the “alternative fiscal scenario”. Data source: Congressional Budget Office.

Of course such a path is completely infeasible and unsustainable. Then what exactly is the government promising to provide in the way of retirement medical care and income for those currently working, and what will the government actually deliver? The answer to both questions is unclear to me, though I have no doubt that this category of off-balance-sheet liability represents a potentially staggering sum.

But whatever you think future spending on Medicare will be, consider some of the other off-balance sheet federal promises. At the end of 2008, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation had insured $4.8 trillion in deposits. Fannie and Freddie, which are now effectively nationalized, bring perhaps another $4.9 trillion in notional liabilities to the table. Those two alone sum to an amount well in excess of the current federal debt owed to the public.

Ah, but the federal government wouldn’t actually be asked to honor more than a small fraction of those guarantees, would it? Only a few banks will fail, and the prime loans insured by Fannie and Freddie are safe, right? Right?

Still, even a modest fraction of $10 trillion sounds like a lot of money to me.

Then there’s the loose change, such as the $1.1 trillion in obligations of the Federal Home Loan Banks. The federal government does not officially acknowledge responsibility for the liabilities of these government-sponsored enterprises, though that of course is what it had also claimed about Fannie and Freddie. Government-owned Ginnie Mae has issued guarantees on another $577 billion in mortgage-backed securities, while the Federal Housing Administration has insured $532 billion in mortgages. The U.S. Federal Reserve has added $1.1 trillion to its liabilities since September. And now loan guarantees appear to be the instrument of choice for U.S. energy policy ([1], [2]).

Of course there’s a simple reason why all this happens. There is tremendous pressure for politicians to deliver in the form of off-balance-sheet commitments. Voters credit them for giving us what we want now, and blame somebody else when the time comes to pay for it. I’m amazed that no one is being held accountable for the fiasco of Fannie and Freddie, and indeed leading elected officials continue to advocate more of the same policies that created the original problem.

Some might look at Figure 1 and conclude that the U.S. could issue much more debt and still find ready buyers. But I worry that Figure 1 is only the tip of a very big iceberg.

Off-balance-sheet federal liabilities

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply