Is borrowing short and lending long a risky strategy for the Fed?

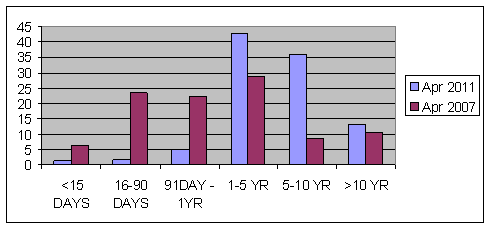

The Federal Reserve today is holding $1.4 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities, which is $600 billion more than it held four years ago. The maturity of those securities has also increased significantly. In April 2007, more than half of those securities were one year or shorter. Today, the fraction is down to 8%.

Percentage of Federal Reserve holdings of U.S. Treasury securities by maturity, April 2007 and April 2011. Data source: H41.

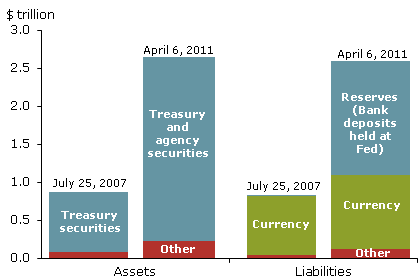

Since 2007, the Fed has also acquired $132 billion in debt from Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Bank, and $937 billion in mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by Fannie, Freddie, or Ginnie Mae. Where did the Fed get the money to buy all this stuff?

The answer is, whenever somebody sold these items to the Fed, the Fed credited an account that the seller’s bank maintains with the Fed in the form of new Federal Reserve deposits. At the moment, most of those new reserves are just sitting there at the end of each day on some bank’s balance sheet. Reserve balances with Federal Reserve banks have gone from $9 billion in April 2007 to almost $1.5 trillion today.

The Fed is currently paying banks 0.25% interest on those reserves, and is collecting an average interest rate of 4% on its long-term securities. That netted the Fed a healthy profit of $80 billion in 2010, which it returned to the U.S. Treasury. In effect, the Fed is borrowing short and lending long, making a huge profit on the difference, and handing it back to the Treasury.

But of course, that only works in your favor when the short rate is below the long rate. At the moment, the short rate is well below the long rate, and historically that has been the average relation. But if short rates rise, is the Fed exposed to a loss on its portfolio?

Federal Reserve balance sheet. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

A recent article by Glenn Rudebusch of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco notes that the risk is substantially less than the simple “borrow short, lend long” interpretation might suggest. The reason is that $1 trillion of the Fed’s liabilities take the form of currency in circulation, which you can think of as funds the Fed has permanently “borrowed” at 0% interest. Rudebusch calculates that the interest rate on reserves would have to rise to 7% in order for the Fed not to earn a positive cash flow on its current portfolio, once you factor in the benefit to the Fed from the fact that a good fraction of its liabilities require no interest payments.

Rudebusch’s conclusion is that if the Fed’s holdings of MBS and longer-term Treasuries are providing a beneficial economic stimulus, fears of interest rate risk to the Fed’s portfolio are not a good reason to alter the course.

Interest rate risk and the Fed

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply