The February Personal Income and Outlays report revealed the drag of higher food and energy costs as a 0.3 percent gain in nominal disposable personal income was knocked back to a 0.1 percent loss in real terms. Similarly, the 0.7 percent gain in nominal spending turned into a just 0.3 percent real gain. While better than the flat reading in January, the relatively weak performance of PCE this quarter will lead analysts to knock down Q1 growth forecasts. I try not to read too much into any one quarter, and tend to view the consumer slowdown in light of the acceleration at the end of last year. Overall, the trend in PCE growth since the middle of last year is consistent with annual gains of around 3% a year. The footing is firming, and it is sustainable, but it is still far short of what is needed to rapidly return consumption to its pre-recession trend.

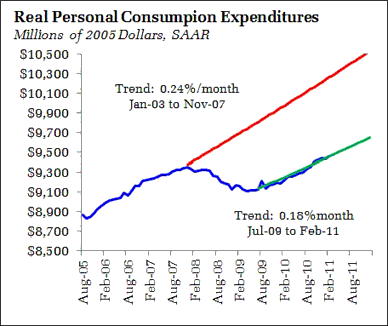

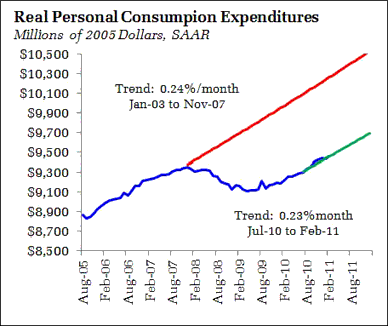

Since the recession ended, real PCE gained at a rate of 0.18 percent per month:

By a year into the recovery, household spending accelerated, and since July of 2010 has grown at 0.23 percent per month, just about the prerecession trend:

The new normal, it seems. On one hand, I have a preference for steady growth over recession and stagnation. On the other, the gap between the new trend and old at least partially reflects the lack of job opportunities for the nation’s unemployed – and few are expecting that situation to change dramatically this year. Even an “optimistic” outlook of 200k jobs a month yields only a small improvement in the unemployment rate. Also note that some of the gains for net new hiring would be offset by reduction in spending power as people fall off the unemployment rolls. And finally, some of the gains in spending are driven by a rebound on auto sales, which will not continue forever. In short, without a force that greatly accelerates job growth and drops unemployment rates quickly, it is difficult to see consumption returning to the pre-recession trend.

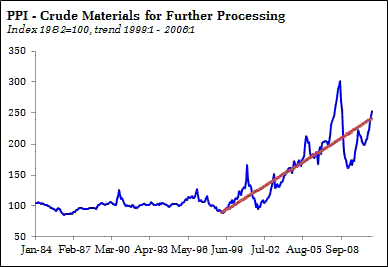

Given that spending accelerated faster than income, the saving rate by definition fell, although it continues to hover around the 6% mark. The higher saving rate provides some cushion for higher food and energy prices, allowing households to absorb and adapt to these price gains without an abrupt change in behavior. It is worth noting that although the recent increases appear dramatic, they are consistent with a return to the prerecession trend:

For much of that period, the economy managed to weather commodity price inflation. It was only the superspike in prices coupled with the evolving US financial crisis that brought spending to a standstill in 2008. Hence, I tend to think the economy can withstand the gains already experienced, but continued gains at recent rates would be increasingly worrisome. Remember, in comparison the previous energy shocks, prices have not yet gone to new highs. Psychologically, we have yet to see new territory.

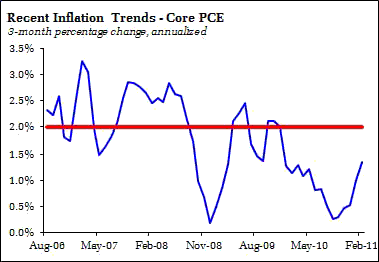

Finally, note that recent core inflation numbers have been ticking up:

This should not have been unexpected as some of the pass-through from higher commodity prices would undoubtedly show up as temporary gains in core inflation. From the most recent FOMC statement:

The recent increases in the prices of energy and other commodities are currently putting upward pressure on inflation. The Committee expects these effects to be transitory, but it will pay close attention to the evolution of inflation and inflation expectations.

Again, see the commodity chart above. Core inflation has remained remarkably stable during the past decade despite the instability of commodity prices. This suggests that overall monetary policy has not been far off the mark.

The real fireworks will ensue if core-inflation accelerates above 2% on a year-over-year basis. I believe that, assuming ongoing high levels of unemployment, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke will tolerate somewhat higher inflation to compensate for the recent period of low inflation. Be forewarned: This will leave inflation hawks, notably Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher, foaming at the mouth.

The steady but uninspiring gains in US economic activity continue to argue for a steady hand on monetary policy. From today’s speech by Chicago Fed President Charles Evans:

With regard to policy today, slow progress in closing resource gaps and underlying inflation trends that are too low lead me to conclude that substantial policy accommodation continues to be appropriate. This accommodative policy will foster a return of economic conditions consistent with our dual mandate.

Please read Evan’s speech for his patient explanation of inflation dynamics. An excerpt:

Monetary policy cannot affect the scarcity of resources. Indeed, think about what happens when the price of a commodity rises but other prices do not change. We call this a change in the relative price of the commodity. Changes in relative prices provide an important signal to market participants, encouraging consumers to find ways to economize and giving suppliers an incentive to increase production. Changes in relative prices are not inflation. Inflation, by definition, is a continuing increase in the general level of prices of all goods and services in the economy.

There is much more in the speech as Evans is doing what all Fed officials should be doing at this point – clearly elucidating the near for policymakers to focus on core, not headline inflation. See also David Altig.

Bottom Line: Try to look through the data to spot underlying trends; this is what the Fed is doing, and it will lead them to complete the current round of asset purchases. Watch energy prices closely, keep an eye on the other risks (Europe, Japan, etc) while awaiting the next big test – the exit of the Fed from large scale asset purchases. The economy stumbled last year when the Fed shifted to neutral. Coincidence, or should have been expected given that housing would not rebound and fiscal stimulus would fade? We will have another test of the importance of the Fed lifeline in the second half of this year.

Leave a Reply