In December 2000, Bill Clinton announced that the “The United States is on course to eliminate its public debt within the next decade.” According to the 2001 budget presented by his administration (during the year 2000), the government debt held by the public would decrease from about 3.7 trillion at the end of 1998 (42% of GDP) to 377 billion by 2013 (around 3% of GDP).

This prediction turned out to be highly inaccurate as today (2010) government debt in the US has reached close to 9 trillion (60% of GDP).

What went wrong? Did the New Economy led to unrealistic macroeconomics assumptions or did the next administration(s) behave differently from what the Clinton administration had predicted?

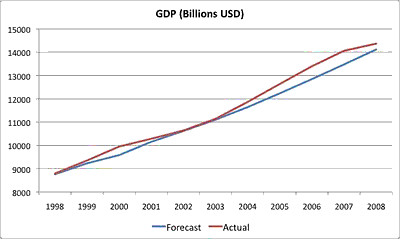

The next two figures helps us understand the source of this forecasting error. Let’s start with the GDP forecast. The macroeconomic assumptions in the 2001 budget were quite reasonable. The path for GDP as predicted by the 2001 budget has been very close to the actual numbers. In fact, by 2008 the actual GDP was slightly higher than what was anticipated in 2001 (Note: The 2009 forecast was, of course, off by a large amount because of the depth of the recession. I stop the series in 2008 because I want to focus on the pre-crisis period. Notice that there was a recession in 2001 that was also unexpected but it did not significantly affect the path of GDP.)

Figure 1. GDP Forecast from 2001 budget compared to actual GDP.

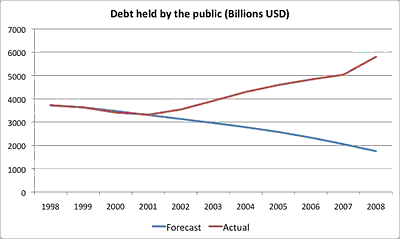

In contrast, the debt held by the public grew at a much faster rate than it was anticipated. Starting with the 2001 year, government debt accelerated and deviated from the optimistic assumption that the government would keep taxes and spending at levels that allowed for a continuous reduction of debt levels towards zero. Taxes were cut and without a restrain on spending, deficits and debt grew.

Figure 2. Government debt held by the public as forecasted in the 2001 budget

compared to the actual figure.

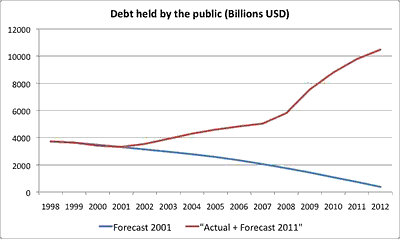

In the figure below I extend the series to 2012 by comparing the forecast made in the 2001 budget as well as the forecast made in the current 2012 budget. After 2008 the two series keep deviating from each other and this time is not all about political decisions, we also have the effect of a worse-than-expected growth performance in the 2008-2010 period.

Figure 3. Government debt held by the public as forecasted in the 2001 and 2011 budgets.

Ensuring long-term stability in public finances is not easy. Governments face uncertainty about macroeconomic conditions and their political choices need to be consistent with their macroeconomic forecasts. What the example above illustrates is that the macroeconomic uncertainty was not responsible at all by the deviation in fiscal policy outcomes from their forecasts in the 2001-2008 period. It was a set of different policy choices after 2001 that sent the budget into larger deficits and the debt levels towards an unsustainable path.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply