Normally when I write about corporate profits, I refer to the earnings of the S&P 500 (see here for an extensive analysis). However, companies in the S&P get a big chunk of their earnings from their overseas operations, and those 500 firms hardly make up the whole of corporate America, much of which is not even publically traded.

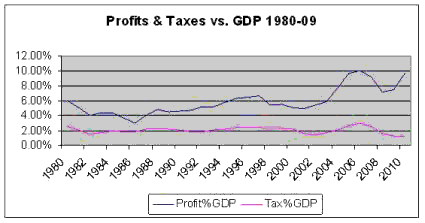

The government does keep track of the broader, and only US, picture. Corporate income taxes are also one of the major sources of government revenue. The graph below shows how corporate profits, and the taxes derived from those profits have done as a percentage of GDP over the last 30 years.

The tax revenue numbers are only available on an annual basis, so to keep things lined up, profits are shown as of the fourth quarter (at a seasonally adjusted annual rate). The exception is for 2010, where the latest data is for the third quarter.

Two things jump off the graph at me. First, as one would expect, profits took a big hit in the recession, dropping by 24.0% from 2006 to 2008 (from 1349.5 billion to $1024.9 billion). As a share of GDP they fell from 10.07% to 7.13%, a fall of 29.2%. Nominal GDP was actually slightly higher in 2008 than in 2006, and earnings really fell apart in the fourth quarter of 2008.

However, even at the low point, as a share of GDP, 7.13% is not all that bad. It is a bigger share of the overall pie than in any year prior to 2004.

They have, however, staged a very impressive rebound, and in the third quarter they were back up to an annual rate of $1416.3 billion, a new record in absolute terms. As a share of GDP, they were running just shy of the 2005 level of 9.71% of GDP.

Given how the earnings of the S&P 500 have done in the fourth quarter earnings season, it is highly likely that the fourth quarter rate will be somewhat higher again, probably edging out the 2005 share, but not quite at the record 2006 rate. The corporate profit share of the economy is running at over twice the share they averaged in the Reagan administration (4.20%).

What About Taxes?

On CNBC and in the Wall Street Journal, seemingly days of airtime and oceans of ink have been spent bemoaning the fact that the nominal corporate tax rate is 35%, which is far higher than in most of the world. However, that tax is filled with all sorts of loopholes, deductions and tax credits. The net result is that many very profitable corporations pay virtually nothing in corporate taxes. The effective tax rate (i.e. actual cash taxes paid to the federal government as a share of reported profits) varies wildly from industry to industry.

Picking Winners & Losers

This is sort of a backhanded industrial policy, where the government is attempting to “pick winners and losers.” However, it sort of came at it haphazardly, not by any coherent plan of which industries the government should be favoring, and which it should be making life difficult for.

Some of the “industrial policy” would probably withstand scrutiny. The effective tax rates are very low for R&D intensive industries like Drugs and Tech, and much higher for less innovative industries such as Retail. That is, if you think that the government really should be in the business of picking which industries should be supported and which should be “punished” with high effective tax rates.

Overall, though, the tax burden on companies has not been rising over the last three decades. As a share of GDP, corporate tax receipts have stayed very close to 2% over the whole time period. The average since 1980 is 2.05%. The record high was in 2006 at 2.95%. The record low was in 2009 at 1.29%.

Unlike corporate profits, the taxes received on those profits have yet to show any real rebound, rising to just 1.31% of GDP in 2010. The collapse in tax revenues (generally, not just corporate income taxes) is a major reason behind the big current federal budget deficit. Individual income taxes, the other major source of funds for the general budget (i.e. leaving out Social Security benefits and payroll taxes) have also fallen sharply, from a high of $1163.5 billion in 2007, or 8.26% of GDP to $898.6 billion or 6.19% of GDP in 2010.

Overall Tax Rate Coming Down

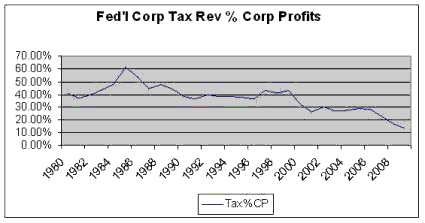

However, if corporate profits are soaring, but the taxes on those profits are not, it means that the overall effective tax rate must be coming down. The next graph shows federal tax receipts from corporate income taxes as a percentage of total corporate profits. This is not quite the same as the overall effective tax rate, as the corporate profits number is after taxes, so the actual effective tax rate is somewhat lower than shown on the graph, but as it is consistent across time, the overall trend is accurate.

This is not a picture of companies being strangled by excessive taxation. Over the entire period, corporate tax receipts averaged 37.15% of after tax corporate profits. The high point was in 1986, when they hit 61.46%. That was a bit of an outlier — the next highest was in 1987 at 53.55%, and in no other year were taxes over 50%.

So how about now? We were at a record low of 13.52%, breaking the 2009 record of 17.15%. In no other year were they below 22.66% (2008). So in other words, during the late Reagan period, the Federal Government was collecting over 50% of corporate income in taxes, and today we are not even at 15%. Yet somehow, people can go on TV and say with a straight face that Obama is anti-business, and never once get a tough question from the CNBC hosts to back up the assertion.

Eliminate the Corporate Income Tax?

There is a good case to be made for doing away with the corporate income tax entirely. Corporations are, after all, “artificial persons.” It is generally assumed that if you tax a company, that the shareholders will be the ones that, in the end, pay up. That assumption does not really hold, though.

Some companies will pass through the higher taxes they have to pay to consumers, or they will pay their workers less than they would have otherwise. Taxing at the corporate level might be convenient for the government, but it really is not clear who (as in actual people with a pulse) is actually bearing the burden.

However, if we were to do away with the corporate income tax, it would not be fair to tax dividends at a preferential rate, and since dividends can be replaced with share buybacks, the capital gains rate would also have to be equal to the ordinary income rate (or perhaps if you want to have a capital gains preference it would only apply to really LONG term capital gains, say assets held for more than 10 years).

Doing so would greatly simplify the overall tax system, and would cut down on lots of tax shelters. After all, one of the key aims of many tax shelters is to “transform” ordinary income into capital gains income. If the two rates were the same, there would be no reason to try to do so. That would be very bad news for the accounting and tax law professions, but good news for the rest of us.

In Case This Is Not Actually Viable

Absent a total repeal of the corporate income tax system, there clearly is a need to reform it, and have the government stop its practice of picking winners and losers through the tax system. In doing so, there is room to bring the overall statutory rate down by eliminating many of the deductions and credits found throughout the system.

Given the big deficit we face, the objective should be to actually increase the amount of revenues even as the rate comes down. If corporate taxes were to return to their long-term average as a share of GDP from the current levels, that would be an additional 0.74% of GDP or $108 billion in revenues for 2011. Not enough to cure the deficit on its own, but enough to make a noticeable difference.

In the meantime, complaints about the government choking business with excessively high taxes should be ignored. If businesses could still breathe with Reagan taking more than 50% of profits, somehow they should be able to survive with Obama taking less than 15%.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply