The Doha Round is likely to conclude this year, as a burst of political leadership by G20 and APEC nations and deft diplomacy by the WTO have spurred talks that are rapidly narrowing the remaining gaps. This column reviews the progress and highlights what more is needed, based on a newly released report written by the High Level Trade Experts Group.

Incredible but true – the Doha Round is likely to conclude this year. The WTO’s current episode of global trade negotiations (a.k.a. the Doha Round) have careened between retrenchments, setbacks, and failures since their launch in November 2001 (Bluestone 2009). The reasons for the long delay are complex, but they never included irreconcilable differences. Pareto-improving packages have always been possible; the hard part was deciding among them (Baldwin 2010).

But all that is history. The negotiations are preceding full speed.[i] The plan is to have the basic political compromise in place by spring and the full package before summer.

What broke the deadlock?

The paralysis of the last two years was primarily due to the Obama administration’s unwillingness to engage the issue, according to my discussions with more than a dozen WTO ambassadors and WTO leaders since August 2010.

Obama needed every Democratic vote to get his domestic agenda through Congress. As trade liberalization is deeply opposed by some Democrats, the administration treated “trade” as a four-letter word – not to be mentioned in any way in any situation. America, the argument went, needed healthcare reform, financial reform, and a stimulus package far more urgently than it needed a trade deal.

The US line that justified stalling on Doha was that the package on offer was the “Bush deal”; the “Obama deal” would require more concessions by other nations. When diplomats asked what concessions the US would offer in return, the room went quiet – and stayed quiet since Obama took office. (For months, the US didn’t even have a WTO Ambassador.)

And then Obama lost his majority in the lower house. Plan A was out; Plan B was in – and this includes the Doha Round. Obama supports multilateral governance in general, is broadly in favour of free trade (his anti-trade remarks on the campaign trail were directed at bilateral deals with low-wage nations, Council of Foreign Relations 2008), and believes that Doha could create US jobs. And there is history.

Bill Clinton pushed for conclusion of the last multilateral trade talk in 1994 to put it before a Republican-held Congress. Here are the headlines when it passed: Boston Globe: “Senate delivers GATT’s final OK; 76-24 trade vote puts US on right path, Clinton says”; New York Times: “Senate approves pact to ease trade curbs; a victory for Clinton”. The 1994 Times article goes on:

“Appearing on the South Lawn tonight with Congressional leaders, including Senator Bob Dole, Republican of Kansas … President Clinton went out of his way to praise Republican leaders …. He called the vote ‘a bipartisan victory that really, really gives our country the boost we need to keep moving forward toward the 21st century to create more high-wage jobs for the American people. We said loud and clear that America will continue to lead the world to a more prosperous and secure place …. Let’s make the GATT vote the first vote of a new era of cooperation.”

As Obama would relish such an opportunity in fall 2011, American trade diplomats have been talking and moving since November. This provides the catalyst for the final chemical reactions necessary to close the deal.[ii]

Heads of state must engage

But beware. While likely to conclude, nothing is sure about this deal. To drive the point home, Germany, Britain, Indonesia, and Turkey created a “High Level Trade Experts Group” in the run-up to the Seoul G20 Summit. The Group’s remit is to identify priority actions on trade, including Doha. The Group, which consists of nine trade experts[iii] appointed by the four sponsoring governments (I was appointed by the Cameron administration), today released an interim report in Davos where trade ministers are meeting informally to take political readings and identify blockages. The key points are threefold, in my view:

- Doha is doable this year; rapid progress is being made in closing the negotiating gaps; this started in November 2010.

- Getting the deal done requires head-of-state attention; they must authorise, or personally negotiate the last trade-offs framed by the draft agreement that their WTO ambassadors hope to have ready for April.

- The window for this deal is the first half of 2011; after that all bets are off until 2013 at the earliest (more on this below).

To stress this point, the Group calls for a hard deadline of 31 December 2011 and sketches out what is known in Geneva as the “landing zone” for a final Doha package.

The window of opportunity: Now or perhaps never

Convergence of unrelated developments create today’s window of opportunity.

- Oversimplifying for clarity’s sake, the Doha deal involves reduced ceilings on agricultural protection and subsidisation in exchange for reduced tariff ceilings on industrial goods. Food prices are high so the agricultural liberalisation won’t hurt farmers much and manufacturing production in emerging market is booming, so the tariff cuts won’t be very politically painful.

- The new trade giants – India, Brazil, and China – are eager to guard the WTO’s central place in the world trade system; inter alia, they fear that US, EU, and Japanese use of deep regional trade agreements could create a parallel system of trade governance that excludes them.

- The EU, having already locked in the agricultural liberalisation unilaterally, is eager to collect the benefits of lower limits on emerging market tariffs on industrial goods.

- The US political parties – both Republicans and Democrats – would rather take the issue off the table before the 2012 presidential election campaigns.

The last point explains why this is a time-limited window of opportunity. If the final Doha package is not before the US Congress by mid-2011, it will get caught up in the electoral cycle. Given the poisonous atmosphere on trade in the US – made much worse by high unemployment and Tea Party populism – the Obama Administration would most likely suspend further talks until 2013 at the earliest. This would pose a very real danger.

If Doha were put on hold until 2013, there is a good chance that it would never get done. The world has changed so radically since Doha was launched in 2001 that the temptation to scrap it and start again (implying that a round won’t be finished in this decade) could prove irresistible. Doha’s negotiating mandate is based largely on leftovers from the 1994 Uruguay Round. China, India, and Brazil would have much greater influence over any new agenda than they did when Doha was launched in 2001.

Gains from finishing

Finishing Doha would yield substantial direct economic and political benefits (WTO 2011). The most commonly heard argument for finishing it, however, is that it would allow the WTO to move on. It would allow the WTO to address so-called “next-generation” trade issues – the rules needed to underpin the multi-directional movements of goods, services, technology, and key personnel that drive today’s most dynamic international commerce.

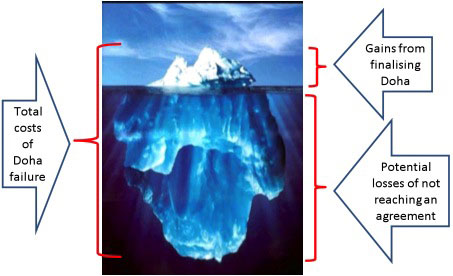

Such issues are now routinely dealt addressed by deep North-South bilateral trade agreements. As I’ve argued, this “21st-century regionalism” is filling the gap that has emerged between 21st-century trade and the WTO’s 20th-century trade rules. If world leaders miss this opportunity to get the WTO into the game, 21st-century trade rules will be set by the network of NAFTA-like trade agreements signed by the US, the Association Agreements signed by the EU, and the Economic Partnership Agreements signed by Japan. As this slide back toward a 19th-century-style Great Powers system would sideline China, India, and Brazil, it could ruin international cooperation on issues ranging from human rights and nuclear arms proliferation to global warming. Figure 1 (borrowed from Antoine Bouet and David LaBorde’s excellent presentation) graphically illustrates the basic point.

Figure 1. Costs of Doha failure

The end game

Trade agreements are like the cat in Schrodinger’s famous thought experiment – uncertainty is what keeps it alive right up to the end. If the Doha Round ever became 99.9% sure of finishing, nations around the world would start piling on “one last demand”, thus killing the deal. My opening claim thus be hedged. The Doha Round is likely to conclude this year as long as world leaders show leadership and get down to making the few final trade-offs needed to move multilateral trade governance into the 21st century. This will not require Herculean feats of political sacrifice – it just requires leaders embrace the sort of “enlightened self-interest” that has been necessary to close every round of multilateral trade talks since the 1940s.

References

•Baldwin, Richard (2010). “21st century regionalism: Filling the gap between 21st century trade and 20th century trade governance,” WTO workshop, 3 November.

•Baldwin, Richard (2010). “Sources of the WTO’s woes: Decision-making’s impossible trinity,” VoxEU.org, 7 June.

•Blustein, Paul (2009). Misadventures of the most favoured nations: Clashing egos, inflated ambitions, and the great shambles of the world trade system, Public Affairs, Washington.

•Bouet, Antoine and David LaBorde (2010), “The Potential Cost of the Doha Round Failure“, presentation at WTO in Geneva, 2 November.

•Council of Foreign Relations (2008), The Candidates on Trade, 30 July.

•High-Level Trade Experts Group (2011). “The Doha Round: Setting a deadline, defining a final deal,” Interim report , 28 January.

•WTO (2011). “Workshop on Recent Analyses of the Doha Round”.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply