Arthur Laffer in the WSJ on June 11, “Get Ready for Inflation and Higher Interest Rates“:

As bad as the fiscal picture is, panic-driven monetary policies portend to have even more dire consequences. We can expect rapidly rising prices and much, much higher interest rates over the next four or five years, and a concomitant deleterious impact on output and employment not unlike the late 1970s.

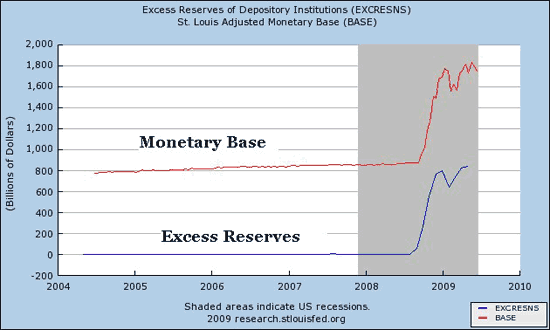

The percentage increase in the monetary base is the largest increase in the past 50 years by a factor of 10. It is so far outside the realm of our prior experiential base that historical comparisons are rendered difficult if not meaningless.

Banks now have huge amounts of excess reserves, enabling them to make lots of net new loans. At present, banks are doing just what we would expect them to do. They are making new loans and increasing overall bank liabilities (i.e., money). The 12-month growth rate of M1 is now in the 15% range, and close to its highest level in the past half century.

Alan Blinder counters in today’s NY Time article “Why Inflation Isn’t the Danger:”

The mountain of reserves on banks’ balance sheets has, in turn, filled the inflation hawks with apprehension. But their concerns are misplaced. To understand why, start with the basic economics of banking, money and inflation. In normal times, banks don’t want excess reserves, which yield them no profit. So they quickly lend out any idle funds they receive. Under such conditions, Fed expansions of bank reserves lead to expansions of credit and the money supply and, if there is too much of that, to higher inflation.

In abnormal times like these, however, providing frightened banks with the reserves they demand will fuel neither money nor credit growth — and is therefore not inflationary.

MP: The chart below shows the significant growth in both the monetary base and excess reserves over the last year. According to Laffer, banks are lending out the excess reserves, which will be inflationary, and according to Blinder, banks are holding onto the excess reserves, which will not fuel inflation.

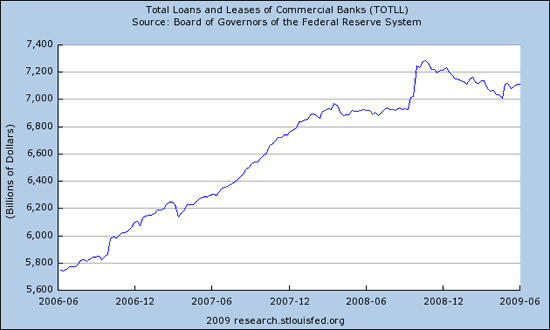

Who’s correct? The graph below of the Total Loans and Leases of all commercial banks suggests that Blinder is more correct, at least for now. Total bank loans peaked in late 2008 and have actually been gradually declining since last October, falling by almost $200 billion from the peak. And the graph above shows that excess reserves at banks have increased lately, which is consistent with the recent decline in bank loans. As the Fed has expanded the monetary base and bank reserves, banks have been holding a majority of those increased reserves as excess reserves, and they are NOT lending them out.

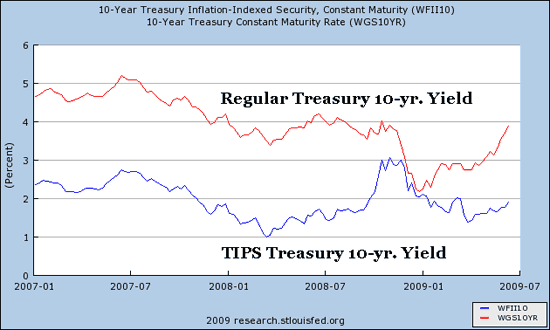

Blinder also argues that the bond market does not seem too worried about future inflation:

The market’s implied forecast of future inflation is indicated by the difference between the nominal interest rates on regular Treasury debt and the corresponding real interest rates on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, or TIPS. These estimates change daily. But on Friday, the five-year expected inflation rate was about 1.6% and the 10-year expected rate was about 1.9%. Notice that the latter matches the Fed’s inflation target rate of just under 2%. I don’t think that’s a coincidence.

MP: The chart below show the recent history of 10-year Treasury yields from both regular and inflation-indexed notes and illustrates Blinder’s point of inflationary expectations of about 2%, based on the difference in yields between regular 10-year Treasuries of 4% and 10-year inflation-indexed Treasuries of about 2%.

Bottom Line: Both the bond market data showing contained expectations of inflation at around 2%, and the commercial banking data showing declining loan volume, seem to support Blinder’s position more than Laffer’s. I’m leaning toward Blinder’s position for now. Inflation is not any kind of “clear and present danger,” at least not yet.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply