The VIX is calculated and disseminated in real-time by the Chicago Board Options Exchange. It is a weighted blend of prices for a range of options on the S&P 500 index, basically targeting a variance swap. As the VIX index does not have a spot analogue like the S&P500, its ETF is derived from the two nearest months of VIX futures, to minimize the discrete jumps as contracts expire. As each calendar day passes, the VXX ETF will sell 1/30 of the first month VIX futures and buy an identical amount of the second month VIX futures, so that the percentage holdings of the front month and second month futures always create a synthetic blend of a basket of VIX futures with a constant maturity of 30 days. The VXX is forever rolling down the futures curve.

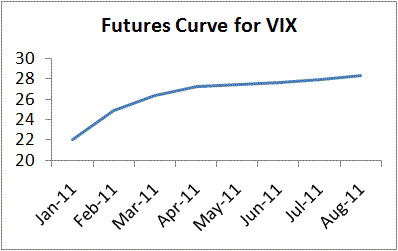

The futures in the VIX has looked like this for the past couple of years:

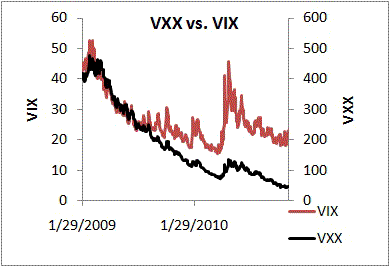

this is contango, when the futures price is above the current price, and is common in Gold futures. As Harvey and Erb (2007), or Gorton and Rouwenhorst (2005) have noted, the roll in futures is predictable: you tend to make money going long futures in backwardization, short futures in contango. Thus, the VXX has declined much more than the VIX since it started trading in January 2009 because it has been riding the roll down the futures curve all the time:

The question, obviously, is whether any risk metric explains why some futures are in contango (usually corn, wheat, silver, gold, and coffee), and others in backwardization (usually that copper, heating oil, and live cattle)?

A prominent early explanation for Normal Backwardization put forth by none other than John Maynard Keynes, on why futures generate risk premium from being long, is that farmers grow wheat, say, and wish to hedge it by selling now, rather than waiting until the season is over. So a speculator buys the wheat now, and takes on the price risk, for which he must be compensated. Futures allow operating companies to hedge their commodity price exposure, and since hedging is a form of insurance, hedgers must offer long-only commodity futures investors an insurance premium. Normal backwardation suggests that, in a world with risk-averse hedgers and investors, the excess return from a long commodity investment should be viewed as an insurance risk premium. Alas, backwardization isn’t so normal.

It is easy to expand this to the other side, however, by focusing not on the producer of a commodity, but the purchaser. Say you are Boeing and buy a lot of aluminum to build airplanes. If you hedge, you buy a futures today, locking in a price. Thus, whether you hedge by buying if you are a consumer, or selling if you are a producer, futures have an insurance-like characteristic. The key seems to be knowing, between consumers and producers, who dominates the futures contracts.

In a diversified worldwide market, however, this hedge reasoning does not work in explaining equilibrium returns. Asset pricing theory tells us that returns are a function of risk. And as most investors are not aluminum consumers or corn suppliers, the net covariance with the ubiquitous ‘nondiversifiable risk factor’ should be at work. If you don’t know what this is, well, you are in good company, but like dark matter, it must exist theoretically.

Just as the needs of a company, its preferences, are unrelated to its stock returns, so too should the futures roll be unrelated to its returns, except as it has a covariance on a priced risk factor. This is due to arbitrage, because investors should be allocating capital in a way so that the price of risk from any source is the same whether it comes from futures or equities. If one can get the benefits of the futures roll and not be involved in the futures commodity—-as most investors are not-—this should be like idiosyncratic risk is in the CAPM: diversifiable, and so unpriced.

If going long the VXX costs money because when volatility spikes up, as in 2008, it offsets predictable declines in equities and other stocks of wealth, insurance worth paying for. While this could be an elusive risk factor sighting, alas, it brings an embarrassment of riches. The equity risk premium is thought to be around 5% by most people (and I think that is too high), while the VXX ‘insurance premium’ has been around -40% annually (the VXX has fallen at a 69% annual rate since January 2009, while the VIX has fallen only 46% annually over that period). This is much larger than any pure risk premium story, and highlights my constant refrain that there is no risk premium. If you see a large return premium, while it invariably has some risk it is generally not generalizable to other assets so it is not a true risk factor, and instead due to some institutional clusterpuck.

Note that a guy with a blog devoted to the VIX discloses at the bottom he is short the VXX, so it seems the more you understand this, the better trade it seems. Just look at the futures curve, and currently the second month is 6% over the first month futures. As long as it is this high, it seems shorting the VXX is as good a trade as any.

If you missed out on the signature theory of finance, that of risk premiums explaining all predictable returns, you might have seen the roll and jumped on it, and you would have been richly rewarded for it. If you thought, ‘sure, 40% is high, but that’s the price of risk!’ you could be an editor at a top research journal. Bad theory makes smart people dumb.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply