In a good society, the living standards of the least well-off rise over time.

One way to achieve that is rising redistribution: government steadily increases the share of the economy (the GDP) that it transfers to poor households. But there is a limit to this strategy. If the pie doesn’t increase in size, a country can redistribute until everyone has an equal slice but then no further improvement in incomes will be possible. For the absolute incomes of the poor to rise, we need economic growth.

We also need that growth to trickle down to the poor. Does it?

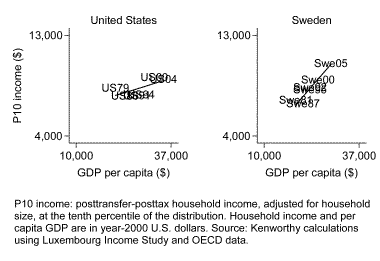

The following charts show what happened in the United States and Sweden from the late 1970s to the mid 2000s. On the vertical axes is the income of households at the tenth percentile of the distribution — near, though not quite at, the bottom. On the horizontal axes is GDP per capita. The data points are years for which there are cross-nationally comparable household income data.

Both countries enjoyed significant economic growth. But in the U.S. the incomes of low-end households didn’t improve much, apart from a brief period in the late 1990s. In Sweden growth was much more helpful to the poor.

In Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom, the pattern during these years resembles Sweden’s. In Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland it looks more like the American one. (More graphs here)

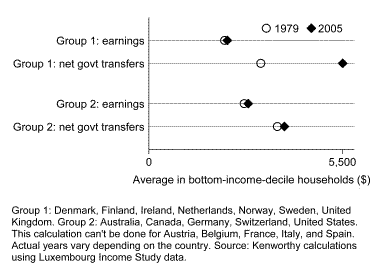

What accounts for this difference in the degree to which economic growth has boosted the incomes of the poor? We usually think of trickle down as a process of rising earnings, via more work hours and higher wages. But in almost all of these countries (Ireland and the Netherlands are exceptions) the earnings of low-end households increased little, if at all, over time. Instead, as the next chart shows, it is increases in net government transfers — transfers received minus taxes paid — that tended to drive increases in incomes.

None of these countries significantly increased the share of GDP going to government transfers. What happened is that some nations did more than others to pass the fruits of economic growth on to the poor.

Trickle down via transfers occurs in various ways. In some countries pensions, unemployment compensation, and related benefits are indexed to average wages, so they tend to rise automatically as the economy grows. Increases in other transfers, such as social assistance, require periodic policy updates. The same is true of tax reductions for low-income households.

Should we bemoan the fact that employment and earnings aren’t the key trickle-down mechanism? No. At higher points in the income distribution they do play more of a role. But for the bottom ten percent there are limits to what employment can accomplish. Some people have psychological, cognitive, or physical conditions that limit their earnings capability. Others are constrained by family circumstances. At any given point in time some will be out of work due to structural or cyclical unemployment. And in all rich countries a large and growing number of households are headed by retirees.

Income isn’t a perfect measure of the material well-being of low-end households. We need to supplement it with information on actual living conditions, and researchers and governments now routinely collect such data. Unfortunately, they aren’t available far enough back in time to give us a reliable comparative picture of changes. For that, income remains our best guide. What the income data tell us is that the United States has done less well by its poor than many other affluent nations, because we have failed to keep government supports for the least well-off rising in sync with our GDP.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply