A large body of research has linked the gold standard to the severity of the Great Depression. This column argues that while economic historians have focused on the role of tightened US monetary policy, not enough attention has been given to the role of France, whose share of world gold reserves soared from 7% in 1926 to 27% in 1932. It suggests that France’s policies directly account for about half of the 30% deflation experienced in 1930 and 1931.

A large body of economic research has linked the gold standard to the length and severity of the Great Depression of the 1930s, primarily because fixed exchange rates precluded the use of monetary policy to address the crisis (see for example Temin 1989, Eichengreen 1992, and Bernanke 1995)

But it has never been entirely clear why the gold standard produced the massive worldwide price deflation experienced between 1929 and 1933 and the enormous economic difficulties that followed. In particular, worldwide gold reserves expanded continuously through the 1920s and 1930s, so it is not obvious why the system self-destructed and produced such a cataclysm.

The standard explanation…

To explain the disaster, economic historians have pointed to the policies followed by central banks. The standard explanation for the onset of the Great Depression is the tightening of US monetary policy in early 1928 (Friedman and Schwartz 1963, Hamilton 1987). The increase in US interest rates attracted gold from the rest of the world, but the gold inflows were sterilised by the Federal Reserve so that they did not affect the monetary base. This forced other countries to tighten their monetary policies as well, without the benefit of a monetary expansion in the US. From this initial deflationary impulse came currency crises and banking panics that merely reinforced the downward spiral of prices.

… and the not-so-standard

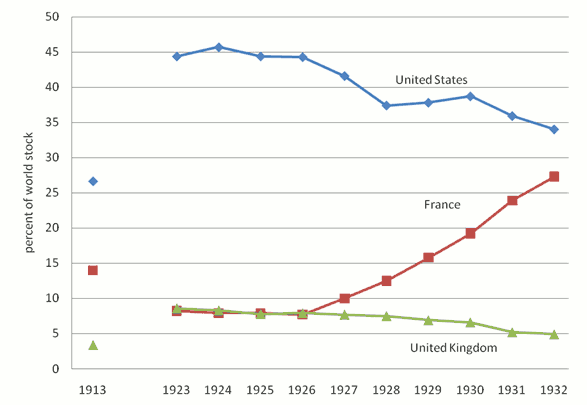

Yet what is often overlooked is the fact that France was doing almost exactly the same thing. In fact, France was accumulating and sterilising gold reserves at a much more rapid rate than the US (see Johnson 1997 and Mouré 2002). Partly as a result of the undervaluation of the franc in 1926, the Bank of France began to accumulate gold reserves at a rapid rate. As Figure 1 shows, France’s share of world gold reserves soared from 7% in 1926 to 27% in 1932.

Figure 1. Share of world gold reserves

The redistribution of gold put other countries under enormous deflationary pressure. In 1929, 1930, and 1931, the rest of the world lost the equivalent of about 8% of the world’s gold stock, an enormous proportion – 15% – of the rest of the world’s December 1928 reserve holdings. This massive redistribution of gold would not have been a problem for the world economy if the US and France had been monetising the gold inflows. Then the gold inflows would have led to a monetary expansion in those countries, just as the gold outflows from other countries led to a monetary contraction for them. That would have been playing by the “rules of the game” of the classical gold standard. But during the interwar gold standard, there were no agreed-upon rules of the game, and both France and the US were effectively sterilising the inflows to ensure that they did not have an expansionary effect.

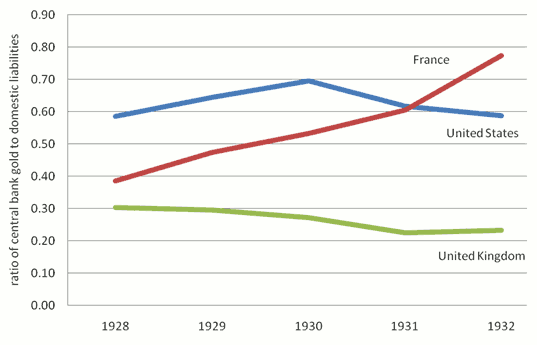

The sterilisation is implicit in the cover ratios presented in Figure 2. The cover ratio is the ratio of central bank gold reserves to its domestic liabilities (notes in circulation and demand deposits). Once again, the change in France is astonishing in comparison to the other countries. France’s cover ratio rose from 40% in December 1928 (the legal minimum was 35%) to nearly 80% in 1932. Between 1928 and 1932, France’s gold reserves went up 160% but the money supply (M2) did not change at all. It is not surprising that France was viewed as a “gold sink” by contemporaries.

Figure 2. Cover ratios of major central banks, 1928-1932

How strong was the deflationary pressure from US and French monetary policy?

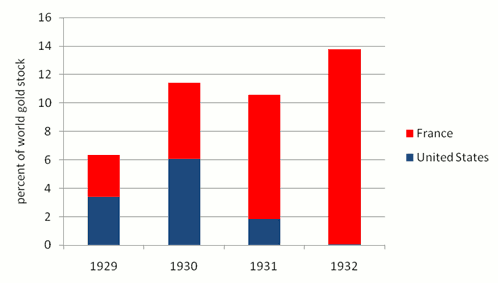

Using 1928 as a benchmark, the amount of excess (i.e., non-monetised) gold can be calculated as the difference between the amount of gold actually held in a given year and the amount of gold required to maintain the 1928 cover ratio for the actual amount of outstanding liabilities. Figure 3 presents the results graphically and reports the excess gold as a share of the world’s gold stock.

In 1930, when the US and France held about 60% of the world’s gold stock, they were sitting on (non-monetising) about 11% of the world’s gold stock relative to 1928. Overall, US and France exerted roughly equal deflationary pressure on the rest of the world in 1929 and 1930 and France exerted a much more deflationary impact in 1931 and 1932. Over the entire period from 1928 to 1932, France had a greater deflationary impact than the US. France could have released 13.7% of the world’s gold stock, while the US could have released 11.7%, and still have maintained their 1928 cover ratios.

Figure 3. Effective reduction in world’s monetary gold stock, 1929-32

The effect on world prices

In his 1752 essay “Of Money,” David Hume remarked: “If the coin be locked up in chests, it is the same thing with regard to prices, as if it were annihilated”. So what was the effect of the effective withdrawal of this gold from circulation on the world price level? In recent research (Irwin 2010), I find that a 1% increase in the gold stock increases world prices by 1.5%. Since the US and France effectively withdrew 11% of the world’s gold stock from circulation, this would have led to a fall in world prices of about 16%. From this simple exercise, we can conclude that the Federal Reserve and Bank of France directly account for about half of the 30% deflation experienced in 1930 and 1931 (see Sumner (1991) for a different calculation that is generally consistent with this finding).

Of course, once the deflationary spiral began, other factors began to reinforce it. The most important factor was that growing insolvency (due to debt-deflation problems identified by Irving Fisher) contributed to bank failures, which in turn led to a reduction in the money multiplier as the currency to deposit ratio increased. However, these endogenous responses cannot be considered as independent of the initial deflationary impulse, and therefore US and French policies can be held indirectly responsible for at least some portion of the remaining “unexplained” part of the price decline.

In sum, economic historians have traditionally focused on the tightening of US monetary policy as the origin of the Great Depression. These findings suggest that the French contribution to the worldwide deflationary spiral deserves much greater prominence than it has thus far received.

References

•Bernanke, Ben (1995), “The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 27:1-28.

•Eichengreen, Barry (1992), Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919-1939, Oxford University Press.

•Friedman, Milton, and Anna J Schwartz (1963), A Monetary History of the US, 1867-1960, Princeton University Press.

•Hamilton, James (1987), “Monetary Factors in the Great Depression”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 19:145-169.

•Irwin, Douglas A (2010), “Did France Cause the Great Depression?”, NBER Working Paper 16350.

•Johnson, H Clark (1997), Gold, France, and the Great Depression, 1919-1932,Yale University Press.

•Mouré, Kenneth (2002), The Gold Standard Illusion: France, the Bank of France, and the International Gold Standard, 1914-1939, Oxford University Press.

•Sumner, Scott (1991), “The Equilibrium Approach to Discretionary Monetary Policy under an International Gold Standard, 1926-1932”, The Manchester School of Economic & Social Studies, 59:378-94.

•Temin, Peter (1989), Lessons from the Great Depression, MIT Press.

![]()

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply