Our St. Louis Fed colleague David Andolfatto declares it is time to bury the old saw that says when it comes to inflation, follow the money:

“One of the ideas that stuck in my head as an undergrad was the proposition that ‘inflation is always an[d] everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’ The idea is usually formalized by way of the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM)—or more precisely—the Quantity of Money Theory of the Price-Level. (QTM is not a theory of money, it is a theory of the price-level).

“In its simplest version, the QTM asserts that the equilibrium price-level is roughly proportional to the outstanding supply of money (however defined). As inflation is the rate of change in the price-level, the phenomenon of inflation is attributed primarily to excessive growth in the money supply (typically viewed as being controlled by the monetary or fiscal authority).”

Andolfatto goes on to note that the monetary base—the sum of currency in circulation and the banks’ reserve balances held at the Federal Reserve (at that page, search “reserves”)—more than doubled since fall 2008, while the rate of inflation fell.

That’s certainly true, though most versions of the quantity theory applied to monetary policy discussions lean on broader measures of money—for no better reason than those measures help the theory fit the facts. Specifically, since the 1980s the phrase “inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon” has in effect meant “inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon when we measure money by M2.”

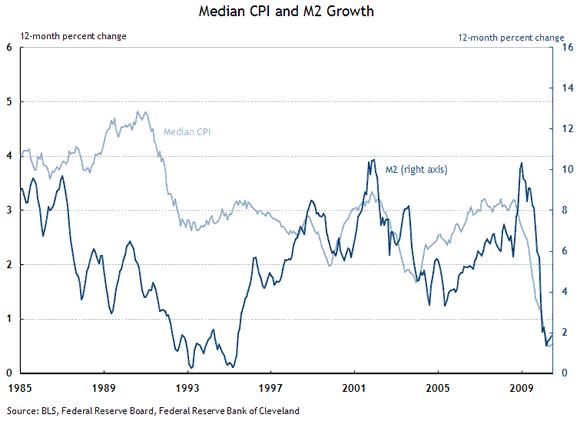

And here’s an interesting thing. If you look at the relationship between M2 growth and core inflation over the past decade and a half, it appears that the money-inflation nexus has been gaining in strength:

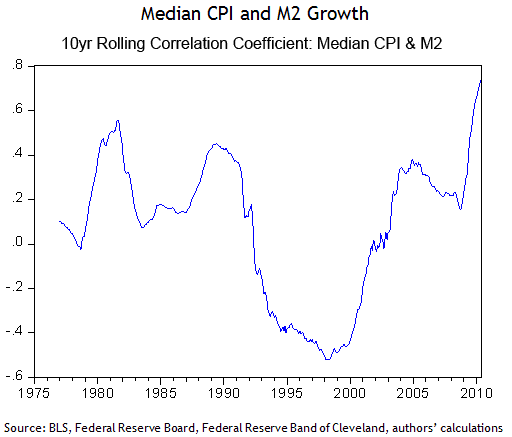

Another way to see this relationship is to look at the correlation between M2 growth and core inflation over rolling 10-year windows:

Could it be that the death of the quantity theory has been greatly exaggerated?

There are plenty of reasons to be cautious. For one thing, it is oft-noted that any connection between money and inflation could be purely coincidental. In fact, if you stare hard at the picture it does appear that changes in inflation often precede changes in money growth. One interpretation is that the same factors that push trend inflation around also result in responses by policymakers or private market participants that ultimately cause the money supply to move in a sympathetic direction.

But even if causation does run from money to prices, the case is not quite solved. The monetary base measure that the Andolfatto post emphasizes has a lot to recommend itself, not least being that it is the measure of money that central banks actually control. The stark disconnect between the growth in currency and bank reserves (the quantity of which is determined by the Fed) and M2 growth (the quantity of which is determined by the decisions of banks to expand their balance sheets) raises legitimate questions about how policymakers would exploit an M2-inflation connection in an environment when the monetary base–M2 connection—the so-called “money multiplier”—has changed so dramatically.

There could be lots of answers to that question. The relatively new Federal Reserve policy of paying interest on bank reserves is one possibility. Andolfatto’s suggestion that all changes in money are not created equal might contain the germ of another explanation. For our part, we think the question is quite a bit more than academic.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply